Books. You’ve heard of them. Some of your favorite movies are based on them. Why not read one? Or ten? I know, it feels like a crime to go around suggesting reading material on a movie blog. It’s bad enough when we suggest you watch foreign films with all of that distracting writing all over the screen, and now this? We are cruel here at Stand By For Mind Control, but remember this: our cruelty is for your own good. We do it out of love. Now shut up and listen!

Here are ten movie books you can’t go wrong with. Are there others even better? There could be. But I’m not going to talk about those. I’m tired and it’s hot out and I just wish you damn kids would stay off my lawn!

10. On Directing Film by David Mamet (’91)

A short, quick read, based on a series of lectures Mamet gave after having directed his first two movies, House of Games (’87) and Things Change (’88). As much about writing movies as directing them, based on the idea that movies work when a series of shots is put together to tell a story. Which sounds very basic. And it is. The problem as Mamet sees it is that most movies consist of “following the protagonist,” resulting in movies that go nowhere, that aren’t engaging, that rely on special effects, wacky camera angles, and pretty visuals to keep audiences interested.

Even if you’re not personally out there writing and/or directing movies, the book is still worth it, simply to understand at a fundamental level how movies work through simple shots edited together to tell a story.

Of course having said that, Mamet is, again, looking at film in a way that ignores a lot of technique, instinct, and the ineffable, logically inexplicable power of images used by many great directors, things Mamet, fundamentally a writer, will never understand. But for the purposes of this book, that’s beside the point.

9. For Keeps by Pauline Kael (’94)

An enormous compilation volume of Kael’s reviews. Yes, one could read all of the original books, but this makes it so much easier, and includes all of her best essays. Kael brought new life to what was then, in the ‘60s, the terribly moribund world of film criticism. Of course she also often has the worst taste in movies imaginable, but no matter. Reading her insane takes on the work of Brian DePalma is all part of the joy.

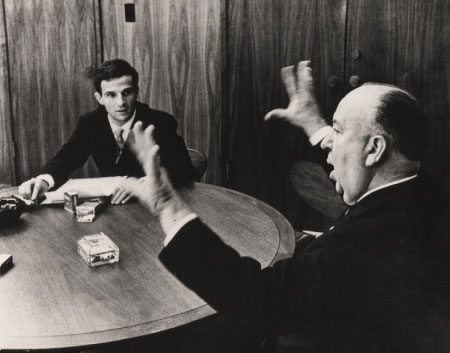

8. Hitchcock Truffaut by Francois Truffaut (’83)

Perhaps the most famous book featuring one director interviewing another. Trauffaut knows Alfred Hitchcock’s work backwards and forwards. He knows what to ask about, from large thematic issues to the tiniest little moments invisible to most viewers. Being a director himself, he sees deeply into Hitchcock’s method. One thing that sticks out in my memory is how Hitchcock would plan his shots so carefully, and shoot only what he knew he needed, that there was simply no way for a studio editor to come in and mess up his work. Without cutting the images together exactly as Hitchcock intended, the scenes wouldn’t make sense. Reading this you’ll want to rent everything Hitchcock ever made.

7. This is Orson Welles by Peter Bogdanovich (’92)

Perhaps the second most famous book featuring one director interviewing another. Once again, Bogdanovich knows what to ask and knows how to get Orson talking. And Orson talking is never boring. You could even say he was a mad genius. Or maybe just mad. He famously had more battles with studios than any director in history, which battles usually resulted in his writing book-length memos on how to properly edit what he’d shot once it had been taken away from him. Probably the most painful part of the book is hearing what the studio did to Welles’s second movie, The Magnificent Ambersons. They didn’t like it, didn’t understand it, and cut out the last hour and had editor (and ultimately great director in his own right) Robert Wise shoot a new ending. Unlike today, when we’d get a director’s cut version on DVD, that hour is forever lost.

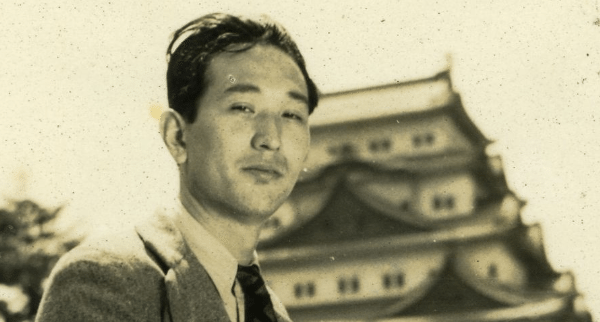

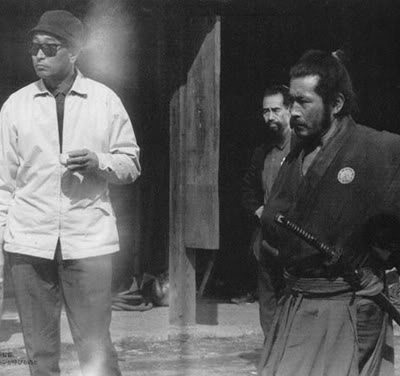

6. Something Like An Autobiography by Akira Kurosawa (’82)

The greatest Japanese director talks about growing up and becoming who he became. The book only goes up to the point of his breakthrough movie Rashomon in 1950, which first brought him international fame, I suppose because by then he was he who was. Maybe he didn’t think the career of an established, famous director was especially interesting to write about. It would then only be about movies. As he says, “I don’t really like talking about my films. Everything I want to say is in the film itself; for me to say anything more is, as the proverb goes, like ‘drawing legs on a picture of a snake.’”

Fortunately, talking about what influenced him growing up, what Japan was like before the war, and after, the process of making his films, and what he learned and how he learned it, is something he does very well.

Here’s his take on the censors during WWII:

At that time the censors in the Ministry of The Interior seemed to be mentally deranged. They all behaved as if they suffered from persecution complexes, sadistc tendencies and various sexual manias. They cut every single kiss scene out of foreign movies. If a woman’s knees ever appeared, they cut that scene, too. They said that such things would stimulate carnal desires. The censors were so far gone as to find the following sentence obscene: “The factory gate waited for the student workers, thrown open in longing.” What can I say?

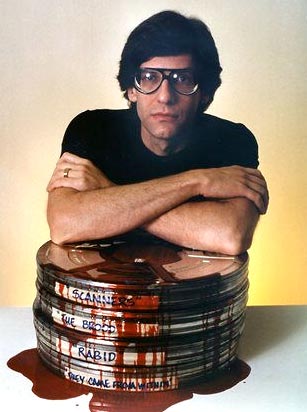

5. Cronenberg On Cronenberg edited by Chris Rodley (’97)

One of a series of books consisting of interviews with directors. This is one of the best. Not all artists have a talent for talking about their work. David Cronenberg does not have this problem. If anything, reading what he has to say about his movies is sometimes better than the movies themselves. He is a thoughtful, philosophical man. His movies are made with specific intent, even the ones that might seem like little more than trashy, if not uniquely weird, horror movies. Another one of those books where once you’re done, you’ll want to watch the director’s entire filmography.

Like Kurosawa, he’s got plenty to say about censorship:

Censors do what psychotics do: they confuse reality with illusion…Censors don’t understand how human beings work, and they don’t understand the creative process. They don’t even understand the social function of art and expression through art…It’s an endless struggle between those who are basically fearful and mistrustful of human nature—and they have ample proof that their version of humanity is right—and those who feel that a truly free society is possible, somewhere.

4. Conquest of The Useless by Werner Herzog (’09)

During the pre-production and filming of his 1982 movie Fitzcarraldo, Herzog kept a notebook. He didn’t write much about the actual shooting of the movie itslef. It’s more that he wrote about everything surrounding it. He wrote about what he was feeling, what he was struggling with. He wrote about the jungle, about the natives, about the deaths and the madness and about how despite everything going horribly, horribly wrong, he perservered. He wrote as only Herzog can write. This book is perfectly wonderful.

If you’ve seen the documentary Burden of Dreams (’82), about the making of Fitzcarraldo, you’ve had a taste of what’s in store for you in this book. But as always, in the book there’s just so much more. Here’s the first page:

A vision had seized hold of me, like the demented fury of a hound that has sunk its teeth into the leg of a deer carcass and is shaking and tugging at the downed game so frantically that the hunter gives up trying to calm him. It was the vision of a large steamship scaling a hill under its own steam, working its way up a steep slope in the jungle, while above this natural landscape, which shatters the weak and the strong with equal ferocity, soars the voice of Caruso, silencing all the pain and all the voices of the primeval forest and drowing out all birdsong. To be more precise: bird cries, for in this setting, left unfinished and abandoned by God in wrath, the birds do not sing; they shriek in pain, and confused trees tangle with one another like battling Titans, from horizon to horizon, in a steaming creation still being formed. Fog-panting and exhausted they stand in this unreal world, in unreal misery—and I, like a stanza in a poem written in an unknown foreign tongue, am shaken to the core.

3. The Battle of Brazil by Jack Mathews (’87)

The story of the making and the release of Terry Gilliam’s Brazil (’85) is by now one of Hollywood legend. Gilliam is the kind of guy who aches for a fight, and Universal was an enemy worth fighting. It’s a totally bonkers story of a bunch of bozos incapable of understanding a truly weird movie desperately trying to edit it into something they perceived as marketable, while on the other side a completely mad artist does everything in his power to enrage, taunt and humiliate the enemy. Each chapter is headed with one of the alternate titles to the movie proposed by the studio, including such winners as:

If Osmosis, Who Are You?

Can Anyone Here Play The Cymbals?

Gnu Yak, Gnu Yak, and Other Bestial Places

The Ball Bearing Electro Memory Circuit Buster

Lord of The Files

Chaos

If you want to understand what goes on behind the scenes at the studios, this is a great place to start.

2. Harlan Ellison’s Watching by Harlan Ellison (’89)

Ellison, writer of a million short stories, some books, and lots of TV scripts, also wrote a metric shit-ton of essays, including a movie column in L.A. during the ‘80s. This book compiles those essays, along with earlier film essays he wrote in the late ‘60s and the late ‘70s. They’re not movie reviews in any normal sense, not by a long shot. Ellison is one of the most enjoyably opinionated bastards ever to put pen to paper, so when he sets out to talk about a movie, he tends to stray far and wide into whatever’s on his mind. He loves movies, and that means bad ones make him angry. And there’s nothing more entertaining than reading his rants. My favorite title to one of his reviews, of the first Star Trek movie: “Star Trek: The Motionless Picture.”

1. Herzog On Herzog edited by Paul Cronin (’02)

That’s right, more Herzog. When I finished this book I thought to myself, “This is my new bible. No. This is THE Bible.” Anyone interested in film, whether or not you know or care about Werner Herzog, should read this. Anyone interested in art should read this. It’s like the world’s greatest manifesto ever written on what it means to be an artist. And not just in terms of film. In fact, even if you have no interest in being an artist, whetever exactly “artist” might mean to you, this is worth reading, because when you’re done you will want to be an artist, or better yet, whatever it is that you are or think you are, you will through this book see a new way of being that person.

You will want to watch every movie Herzog ever made once you’re done with this. And when you watch them, not a single one will disappoint. When asked what the difference for him is in making fiction films versus documentaries, he says there is no difference. He says that for him that distinction doesn’t exist. He is not interested in what documentarians imagine to be “objective truth.” He is interested in what he calls “poetic truth,” which to him is the only truth, and is the one he searches for no matter the subject of his films.

In short, the man is just beautifully insane. I mean inspiring. Beautifully inspiring.

Now put down the remote control and go read one of these. Or all of them. Or best of all, tell me what books I’ve foolishly failed to put on this list. I could use some more great movie books.

I give my strongest recommendation to: The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film (Michael Ondaatje, 2002). The book offers thoughtful, fascinating discussions between Murch (the film and/or sound editor of such films as The Conversation, The Godfather I, II, and III, Apocalypse Now, and The English Patient) and Ondaatje (author of the novel, The English Patient). Reading the book will make you want to watch again these and other worthy films, and you will enjoy them even more for having read the book.