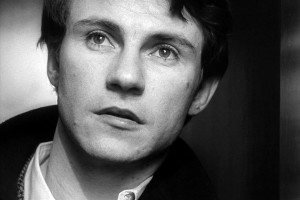

After film school, Martin Scorsese spent four years making his first feature, Who’s That Knocking At My Door? (’67), starring the then unknown Harvey Keitel. It didn’t make a splash. His next feature was for Roger Corman, a sort-of Bonnie And Clyde rip-off called Boxcar Bertha (’72). Scorsese showed it to his friend and mentor John Cassavetes, who told him, “Nice work, but don’t fucking ever do something like this again. You just spent a year of your life making a piece of shit. Why don’t you make a movie about something you really care about.” So Scorsese made Mean Streets (’73).

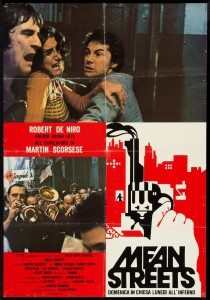

While the script was being written and re-written, and Scorsese was trying to drum up interest in it, Corman offered him $150,000 to re-write it and make it with an all-black cast, to trade in on the popularity of Shaft. Scorsese declined. Meanwhile, he met Robert De Niro, who’d yet to star in a movie. With De Niro playing the fucked up Johnny Boy, and Keitel playing the conflicted Charlie, Scorsese made the movie, shooting exteriors in New York, and interiors in L.A.

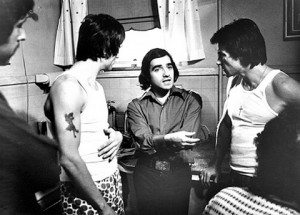

I hadn’t watched Mean Streets for maybe twenty years when I put it on last night. I liked it better than I remembered liking it long ago. I’d forgotten how much of Scorsese is in it. The way he moves the camera—and the camera is always moving—the themes of religion and violence, the naturalistic conversations. It’s very much the precursor to movies like Raging Bull and Goodfellas. At the same time, it’s real thin on story, and it’s kind of slow and meandering. Yet even in its meandering moments, it’s the kind of movie you can’t look away from.

It’s about Charlie, a seemingly smart young man, who’s making inroads with the mob, and Johnny Boy, a neighborhood loon who Charlie has taken under his wing. He’s the cousin of the girl Charlie’s screwing and refusing to commit to, Teresa (Amy Robinson). Charlie looks out for Johnny Boy, tries to fend off his many debtors, despite Teresa, along with everyone else, telling him not to bother. Everyone thinks Johnny Boy is beyond help, beyond redemption. Which is the crux of it. Charlie is deeply conflicted about his religion. The Hail Marys and Our Fathers aren’t doing it for him, they’re not absolving his life of petty crime. He decides on Johnny Boy’s salvation as his penance. In one scene, Charlie holds his own hand in a fire. He wants to be burned clean of his sins, and doesn’t know how to do it.

A lot of the movie is just the guys hanging out, talking, fighting, debating what the hell the word “mook” means, and whether you can call a guy one. It’s shot with this kind of vertiginous, forward moving intensity. The camera is always off-balance, moving into faces, following people around. It gives the movie a lot of life. There’s a great scene in an alley behind a bar where Johnny Boy explains to Charlie why he didn’t pay off on his debts last week. It’s a great, long, rambling monologue by De Niro. Apparently, when Scorsese screened it for friends before its release, Brian De Palma told him to cut the scene. Scorsese did so, but put it back in later. Which just goes to show what a moron De Palma was (and always would be).

Says Scorsese: “I was raised with them, the gangsters and the priests. And now, as an artist, in a way, I’m both a gangster and a priest.”

It’s easy to see why Mean Streets made the impact it did when it came out. It fits in with the aesthetic of the times, but this was a brand new aesthetic, so at odds with everything from the ‘60s. Real guys from the real neighborhood, hoodlums and hucksters, hanging out, just doing what they do. It’s commonplace by today’s standards (in regard to the guys hanging out; it’s not commonplace in its craftsmanship), but in ’73 the notion that you could make a movie like this was brand new.

Charlie puts off all of the decisions he has to make. Will he fall in love with Teresa? Will he be a numbers runner? What will he do about Johnny Boy? Will he find absolution in the church? He puts everything off until it all comes apart in an explosion of violence, similar to how Taxi Driver (’76) would end three years later.

It was a critical hit. Pauline Kael called it the best movie of the year. But it came out within a week of The Exorcist, also released by Warner Bros., and with the vast truckloads of money they’d spent on that one, they didn’t have any time or interest in figuring out how to market the low-budget Mean Streets. Mean Streets was big in New York, but nowhere else. It was sold as a gangster flick, which it clearly wasn’t.

Scorsese, not wanting to be pigeon-holed as a director of Italian gangster movies, chose Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore as his next picture. Which also did all right. But Mean Streets is the movie that really began his career. After Paul Schrader saw it, he knew Scorsese was the man to direct Schrader’s Taxi Driver script.

Mean Streets is the kind of movie you watch and think, damn, who directed that? This kid’s going places! And so he did. Check it out.