Picture this: An art installation, comprised of a largish quadrilateral of cobblestones, lifted from a courtyard and encircled with a line of luminescent wire. To this mundane and largely inconsequential square of stone and mortar, a bronze plaque is appended, which reads:

Picture this: An art installation, comprised of a largish quadrilateral of cobblestones, lifted from a courtyard and encircled with a line of luminescent wire. To this mundane and largely inconsequential square of stone and mortar, a bronze plaque is appended, which reads:

The Square is a sanctuary of trust and caring. Within it we all share equal rights and obligations.

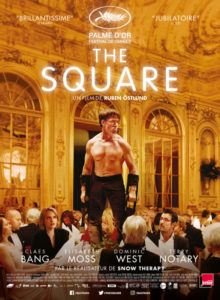

That is The Square of The Square, a place in which the strain of messy human connection is lifted—at least in theory. It is both the center of and counterpoint to the film, The Square, a reasonably brilliant picture written and directed by Ruben Östlund. It is the art within the art, and art that is so preposterously less-than the life that surrounds it, in the art. And this so much so that one almost forgets it exists—The Square—except as a commentary on everything else which exists in The Square. Which—everything—is far more interesting and, often, quite funny.

That is The Square of The Square, a place in which the strain of messy human connection is lifted—at least in theory. It is both the center of and counterpoint to the film, The Square, a reasonably brilliant picture written and directed by Ruben Östlund. It is the art within the art, and art that is so preposterously less-than the life that surrounds it, in the art. And this so much so that one almost forgets it exists—The Square—except as a commentary on everything else which exists in The Square. Which—everything—is far more interesting and, often, quite funny.

Now picture this: a woman (in this case, the sublimely talented Elisabeth Moss, playing a reporter named Anne) confronting the man she has slept with (Christian, played by Claes Bang, curator of a modern art museum) in one of his exhibits, which consists of a teetering stack of wooden school chairs. In the otherwise hushed room, the actual chairs are accompanied by the recorded sound of those same chairs creaking back and forth and back and forth until they collapse in cacophony.

The conversation between Anne and Christian is awkward in the extreme, as she presses him about who he is and why he has done what he did, much as a prosecuting attorney might. Her questions are the type that can elicit defenses, but not answers, for who knows exactly why we do what we do (especially when what we do is as untethered as what Christian has done). Anne and Christian’s human connection, which is so brittle and unsteady, is in The Square mirrored by some forced piece of art that only accentuates how fabricated art is when compared to life.

I will admit, however, that this doesn’t sound funny when I describe it—though it is. Just as in Östlund’s Force Majeure, which I loved, the awkward anxious comedy here pushes you to the precipice of discomfort and over into the chasm of self-recognition.

If anything, however, The Square is far funnier than Force Majeure, with equally delicious scenes of unexpected occurrence. It is, on the other hand, not nearly as succinct nor as apt, wandering afield into questions of what human connection can be before meandering to a close.

This idea, that one can create a space and—through art, or design, or coercion, or anything else—make people behave within it might be the most inane thing I’ve heard in a year full of inane things. And yet, presented in The Square, in the context of all the other preposterous art that is designed to provoke reaction and create connection, its inanity only rises to the top when the film is done and you ask: what did I just watch and why?

This idea, that one can create a space and—through art, or design, or coercion, or anything else—make people behave within it might be the most inane thing I’ve heard in a year full of inane things. And yet, presented in The Square, in the context of all the other preposterous art that is designed to provoke reaction and create connection, its inanity only rises to the top when the film is done and you ask: what did I just watch and why?

I have an answer to that question, but it is one with which the filmmaker has had the bad form to disagree. While the press notes to the film describe its genesis as an actual art project inspired by gated communities, nowhere does Östlund mention the fact that The Square in The Square is indubitably a stand-in for a mobile phone: a glowing right-angled slab inside which we delude ourselves into the belief that humanity can be trusted to behave, simply because we’ve been asked to nicely.

It is brilliant and, alas, not what the film is deliberately about—but no matter. Films are about what we see in them, and in The Square I see our relationship with the artifice of ‘social media’—which is really neither social nor media. It’s just a ruse, a feint for interaction peppered with emoji.

And, although it really needn’t be said, an emoji is not an emotion, even if we’re talking about a smiling pile of poop.

Also not worth saying is that to expect people to behave within the ‘square’ of screen time—now really all the town square we’ve got left—is beyond delusional. People can barely hold it together when they’re face to face; when they’re bounced off two different satellites and compressed into an avatar and only a click away from an animated gif of Goose giving Maverick a high-five: forget it. We are all pwned.

Also not worth saying is that to expect people to behave within the ‘square’ of screen time—now really all the town square we’ve got left—is beyond delusional. People can barely hold it together when they’re face to face; when they’re bounced off two different satellites and compressed into an avatar and only a click away from an animated gif of Goose giving Maverick a high-five: forget it. We are all pwned.

So, while it’s sad that Ruben Östlund doesn’t understand his own brilliance, he did at least win the Palme d’Or for The Square, and that might be consolation enough. I’ve not mentioned the scene with the condom, nor the chimpanzee, nor the viral marketers, nor the ferocious Arab boy who demands his apology with Better Off Dead relentlessness. All of those bits, and many others, are divine.

And I can’t help but notice that what passes for real connection in The Square happens not face-to-face, but through the filter of a screen. The actual interpersonal interactions turn out, invariably, to not be what anyone thought. The real town square is just as chaotic and repugnant and rude, only that doesn’t surprise us anymore. We’ve saved our opprobrium for those who dare abrade us online.

That’s perfectly appropriate as The Square is a film that does not give you what you expect, at any moment. Scenes build like multicar pileups in heavy rain, ideas and desires slamming into each other because there is no way to stop them from doing so. More than anything else, this is what I appreciate about Ruben Östlund’s work. Christopher Laessø, playing Christian’s assistant Michael, earns some of the film’s most understated but exceptional moments of pathos and confusion along these lines.

If you’ve seen the trailer, you’ve also seen a bit of Terry Notary (pictured in the animated gif above) playing the artist Oleg acting as a chimpanzee as an art experience at a fancy dinner. This scene, coming as it does in the middle of the film, pushes everything to its extremities. The Supreme Being felt it knocked the film askew—too unbelievable to accept—but the more I think about it, the more I think it’s right:

Here we are, pretending to be civilized as others pretend to be uncontrollable, each pretending for all he or she is worth until the whole room snaps and we all regret everything we’ve ever done.

I highly recommend you see The Square. It is one of the best films I’ve seen this year.

Meanwhile, I don’t think the ape scene knocked the film askew. It’s more that once it arrived, it felt unreal, there to make a metaphorical point, in a way that the scenes leading up to it did not. Thinking about it now, it strikes me as the kind of scene a writer would imagine at the beginning of the process, the scene that defines and inspires the movie you want to write, and then you write the movie such that it fully encompasses the meaning contained in that one scene, and thus the one scene isn’t needed anymore. So on the one hand, it is, in a way, the best scene in the movie, yet it’s also extraneous. If that makes any sense.

But so anyway, it’s an interesting movie, for sure, with many great moments. I think it just petered out a little early for me, its meaning seeming to dissipate.