Timecop, the Jean-Claude Van Damme time travel movie beloved by, er, no, sorry, forgotten by everyone, contains my favorite worst-ever time-travel-movie-moment ever, where Van Damme is brought to the warehouse where the time travel ship is mounted on some old train tracks or whatever. The creepy guy in charge explains that the craft must reach a certain speed along the tracks to leap into another time. He points to a black speck on the concrete wall at the end of the tracks and says, if the ship fails to reach the required speed, it hits the wall, everyone dies, and that little speck is the result.

And I’m always thinking at that point, why not some soft cushions? Instead of the concrete wall? Why have a wall at all? Why not longer tracks terminating in a pleasant meadow?

Logic. The bane of time travel movies. One of the major draws of time travel is the notion that one can go to the past and change things for the better. But think on that for a second, and you might be clever enough to notice that the past already happened. You can’t not have been in the past in a time machine as of now, but five minutes from now, when you climb in your time machine and go, have been. It already happened. If you were there then, then there you will go now.

What about killing yourself in the past? How’s that paradox work out? It’s not a paradox at all. It’s not a matter of whether or not you can or can’t kill yourself. It’s that you didn’t kill yourself. You’re alive now to go back in time, after all.

What I think is most interesting about time travel is the realization that if someone appears from the future, then the future is already there. Or then. It’s somewhere. It’s somewhen. If someone came from it, then in one very real sense it can’t be that it hasn’t happened yet.

Time is a dimension, after all. The dimensions of space, the three we’re familiar with and the seven other ones those clever physicists say are out there, are everywhere at once. Why shouldn’t time be everywhere at once too?

Which brings up the notion of free will. If time travel were to exist, it would be awfully difficult to argue that free will did too. Even without time travel that’s a tough argument to make. But let’s leave that one aside for this essay.

So the trick with a time travel movie, the same as with any movie featuring an impossible scientific reality, is to explain the logic of of your impossible whatever enough to make it sound plausible, but not so much that it tips back over into bullshit. If there’s too much explained, there’s too much opportunity to find gaping holes.

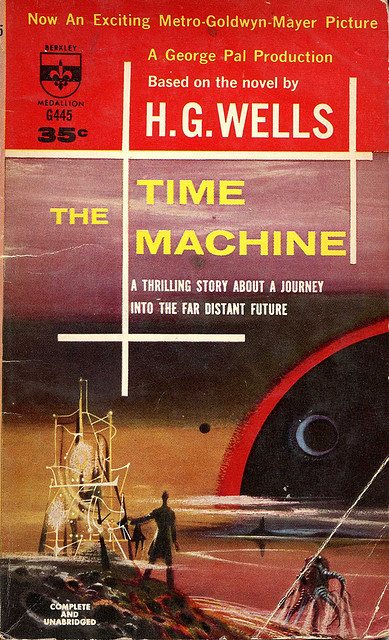

The best way to avoid all the arguments over how and whether one can change the past is to have a story where your time traveler goes only to the future. That’s what H.G. Wells did when he wrote his 1895 novel The Time Machine (in which he coined the term and invented the idea of a ship able to travel to a given point in time). His traveler goes 800 thousand years into the future at first, then beyond that by another 30 million years. Wells did not lack for ballsy imagination.

Few movies deal only with travel to the future. Most famous is one I’m not even going to mention, lest I spoil it for some unlikely soul. Let’s just say that you really did it, you maniacs! You blew it up! God damn you all to hell!

Then there’s Nicholas Meyer’s Time After Time, which actually features the character H.G. Wells and his time machine, used by, of all the luck, Jack The Ripper, to escape capture. Wells follows him to ’79. Light comedy ensues.

The best time travel movie of all time is a short, Chris Marker’s La Jetée (’62), the basis for 12 Monkeys (’95). It makes the smart choice of explaining nothing scientific. There’s no faux logic to have a problem with. Time travel exists. The movie is a poem about one man’s life, featuring a loop, shall we say, far more simple and profound than anything Looper suggests.

Another great example, of course, is Time Bandits (’83). Again, no real explanation is given for how time travel works. The bandits stole a map from the Supreme Being, which map shows the time holes they leap through. Can’t argue with that. There’s no alteration of the past, no changing futures in Time Bandits. The movie isn’t about that. It’s about good and evil and little people hitting each other.

Nicolas Meyer returned to time travel, this time to the past, with Star Trek IV, in which our heroes travel to 1986 to steal a pair of whales. The method used is the old slingshot around the Sun gambit, used on the original Star Trek TV series, so you know it really works. Like Time Bandits, no mention is made of altering the future by mucking around in the past.

Speaking of Star Trek, perhaps the most famous episode of all is Harlan Ellison’s “The City On The Edge of Forever”, in which the crew beams down to a desolate planet and encounters a portal. A drug addled McCoy leaps through it and suddenly the Enterprise no longer exists in orbit above them. McCoy altered time. Why didn’t the whole crew disappear? Because they’re on the planet before the mysterious time portal, “mysterious” being the key word. Nothing is explained, so one allows for this portal to have created a space out of time. Why not? It’s alien. Kirk and Spock jump through to the past, and restore the proper order of events.

Yes, that’s all well and good, but what about this Looper disaster? We’re getting there. Hold on. First we need to talk about The Terminator.

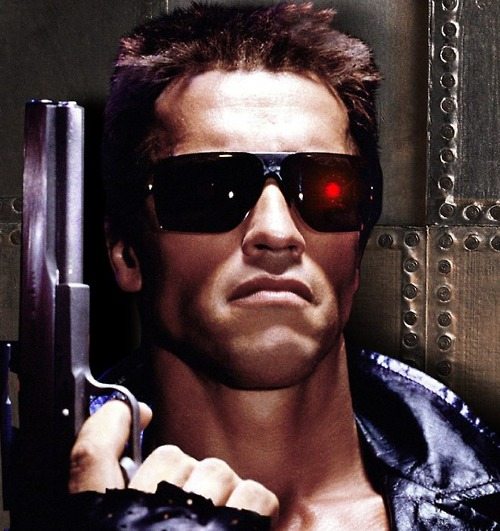

The Terminator (’84), James Cameron’s best movie (after all, he “borrowed” the plot from Harlan Ellison), features a situation where characters fully believe they may alter the future, yet find they are unable to. Skynet, the robot overlord of the future, is theatened by a rebel leader, John Connor. It sends a terminator back in time to kill his mother. Connor sends back Kyle Reese to prevent this from happening (he and Skynet know it doesn’t work the moment the terminator goes back, of course, but see below on this matter). The terminator is stopped, and it turns out Reese is the man who impregnates Sarah Connor with John. That’s good time travel stuff right there.

Skynet, not yet convinced that John’s continued existence suggests time’s inalterability (they’re robots, after all), sends a better teminator back to kill a young John, and we get Terminator 2, in which we learn that the surviving pieces of the original terminator, once reverse engineered, are the very things allowing the creation of Skynet in the first place. The future inspiring the past to create the future. This is a concept of time travel as descibed above, wherein all time is already there, such that notions of causality become difficult to wrap one’s head about.

To make sense of this, one needs only to remember that what happened in the past always happened in the past. Just because an element of importance came from the future doesn’t mean the future had “to be arrived at” before the past event could “happen.” The past already happened, and in a very real way, so did the future.

Terminator 3? No one remembers what happened in that movie. Terminator 4 is where things might have become interesting again (alas, abandon all hope ye who enter here). Now we’re with the adult John Connor. He meets young Kyle Reese, the guy he’ll need to send back in time to have sex with his (John’s) mother. Weird. Now what’s great about this set-up is that John is alive. He knows all this business of sending back terminators to wipe out his existence fails. He knows that no matter what action he takes, he will live long enough to at least send Reese back in time, and to send the terminator of part 2 back as well.

And that’s a weird thing to know. That you can’t make the wrong decision. We’re back at having no free will. Yet the conflict is that no matter the reality, we feel like we have free will. John still has to make decisions. Other lives are at stake. Even if he knows he will necessarily make the decision that keeps him alive, he’s still the one who has to decide. Maybe we can forgive Terminator 4 for not plunging into these philosophical waters. But we’re not going to forgive it for being so dumb I wanted to beat myself over the head with a live tuna by the end.

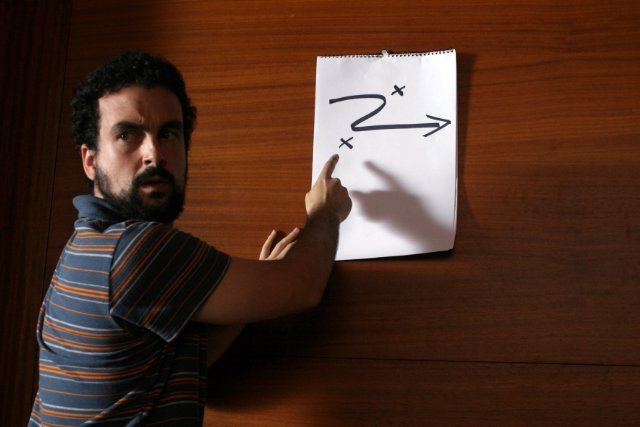

The Spanish movie Timecrimes (Los cronocrímenes, ’07) is another, albeit much less explodey, movie where what happened in the past already happened, where going back to change things you end up doing nothing but what you already did. The movie lacks a compelling story, unfortunately, but it very clearly shows what I think of as the most simple and logical conception of time travel. It’s so simple you only need two x’s and a squiggly arrow to figure it out.

Finally we get to the magical world of magic, i.e. time travel movies where not only is a time machine in the offing, but all kinds of wonderful magical impossibilities turn up too. This is where we have alternate timelines, multiple universes, photos that mysteriously fade away, people who mysteriously fade away, memories instantly altered and erased, etc. and so on. Which look, this is all fine. We’re talking movies here. It’s just that these elements are often associated with lazy storytelling. They are quick and easy and logically lacking ways to have one’s cake and eat it too. They are methods that elide the thorniest issues time travel brings up.

And this is the world inhabited by Looper (’12). No matter what kind of wacky conception of future-altering, alternate universe inabiting, time ripple inducing time travel you put in your movie, you need to be consistent. This is true of any movie. You’re free to invent the rules of your world, but if they’re not consistent, if they change when it suits the story, you’re left with sludge.

Looper’s time travel makes not one lick of sense. It actually seems to include every imaginable conception of time travel all in one movie, such that what it’s left with is a past that has no bearing on the future.

The trouble starts instantly in Looper. The set-up is this: we’re in the future some 30 years. Another 30 years down the road time travel is invented. But it’s illegal. Only bad guys use it. Lacking imagination, all they use is it for is to send people they don’t like back 30 years to be killed by loopers, because it’s tough to dispose of bodies in the future.

I know the set-up isn’t the part of the movie I should spend all my time worrying about, but come on. One’s brain is one’s brain. It likes to think about stuff. Like, why is it hard to dispose of bodies in the future? We see this future. It doesn’t look very hard. Why are these folks sent back still alive? Why not shoot them in the future and then send them back dead? Why send them back 30 years? How about, oh, say, a million years? Alive or dead, it wouldn’t matter, would it? Even 500 years and you could just wipe your hands of them. Why bother with these loopers at all?

Okay, whatever, we’ll let that slide. Next we learn that to “complete the loops”, whatever the fuck that means, loopers have to kill their future selves. For every looper a day comes when he shoots a new arrival from the future only to find that it’s himself as an older man. Fine, “completing the loop,” it has that ring of something that means something, but—wait—what? Why does it matter 30 years down the road if these guys are still alive? What’s that got to do with anything at all? I don’t know. I don’t think writer/director Rian Johnson does either.

Then there’s maybe the dumbest thing of all: why are loopers assigned to kill themselves, when that’s exactly what causes all the trouble? Quiet, brain! We wouldn’t have a movie otherwise, would we?

WE NOW TRAVEL INTO THE LAND OF ENORMOUS SPOILERS

YOU HAVE BEEN WARNED

Looper is a classic case of a reverse-engineered screenplay. Johnson knew how he wanted this movie to end. The notion of “completing the loop” is a poetic and meaningful one to him, I would assume. So he had to figure out how to make a story that reached that point. Convolutions aplenty are usually the result of such a method.

Our hero is Joe (Joseph Gordon-Levitt). We know from the preview that he’s going to let his older self (Bruce Willis) get away instead of shooting him. But in the movie, we first get to see another looper, Seth (Paul Dano), do the same thing. Seth lets his older self run away. The looper organization instantly knows this (how? it is never explained), captures him, and begins slicing off his fingers, his feet, his legs, his nose.

How do we know this? Because the older version of himself, running away, watches his fingers and feet and nose vanish right before his eyes! The scars of words long ago carved into his arm appear magically to tell him where to go. He goes there and is shot dead. Presumably his younger, mutilated self is kept on suicide prevention watch for the next 30 years to make sure this future comes to pass.

Which future? You know, one where his older, mangled self is sent back to be—wait a second, his older self came back whole. We just saw that. Like, thirty seconds ago. Oh, right, I see. This movie makes no sense at all. The past happens before the future, but not really. Only when it’s convenient. Or maybe it’s because the future self is now in the same time as this particular past self, so now a new timeline has been created and—or no, that’s absurd, it’s that it’s an alternate universe, one where the moment the past self sees future self, the universe breaks in two—or, wait, okay, it’s that by seeing each other, all things change and there are no realities, there are only potentialities, so only some things have happened, and others not, depending on which waitress brings you coffee and, um, or, the, but, argh!

These same nonsensical shenanigans continue as Joe finds himself face to face with himself. Old Joe appears, and gets away! We follow young Joe for awhile as the mob guys hunt him down, then abruptly cut back to the scene of old Joe’s arrival. Only this time he’s got the standard sack over his head and young Joe shoots him. A montage of Joe’s next 30 years plays out, he turns into Bruce Willis, he gets married, he shoots a lot of guys (guess body disposal issues weren’t so big a deal after all), and then, as he’s taken away to be sent back in time, he kills his captors, and shows up in the past to enact the original version of the scene where young Joe doesn’t shoot him. Whew. Got that? In other words, the past that happened didn’t happen, because if did, then this movie wouldn’t exist.

I would hope that faced with such observations, Mr. Johnson would say that the mechanisms here aren’t the important thing, The important thing is the emotional journey of the characters. Which is fine. That should be the important thing in any movie. But if you set up a giant time travel plot and fail to be even a tiny bit consistent or logical, nothing else is going to matter.

And anyway, what is Joe’s emotional journey? It’s impossible to say until the end, when, through some serious brain squinting, you concede that it has something to do with his learning not to be selfish, played out by having him kill himself to let the magical wonderboy live.

Did I forget to mention the magical wonderboy? See, also in the future some people are telekinetic, because, you know, the future, especially this one kid who’s like super-telekinetic, and in the future he turns into the Rainmaker, this guy who kills off all of the loopers and stops the whole time travelling by bad guys business. So this kid must be stopped! Older Joe will kill him at all costs!

Wait, why again? Isn’t it a good thing that someone stopped all of the loopers? Aren’t loopers a bunch of murderous, selfish bastards? Doesn’t the ending, where young Joe shoots himself dead, causing old Joe, seconds away from killing the kid’s mother (thus sending the kid on his life’s journey to become the Rainmaker), to vanish into thin air (magic!), represent not a beautiful, touching act of selflessness, but a much larger, much more selfish act of insuring the existence of this insane looper scheme with no one ever to stop it?

Presumably we must assume that letting wonderboy’s mom live turns him into a sweetheart, such that he grows up and not only does away with the loopers, just like he always did, but does it as a much nicer, better behaved person who also does many other nice things with his super-kinetic abilities.

That is, unless his mom, allowed to live, and who is herself powerfully telekinetic, has more children, and they too are super-telekinetic, and so there’s this awesome war of the super-telekinetics in the future, and when time travel is invented, they get their hands on it, because hey, they’ve got superpowers, they control the entire world, and they start sending others like themselves throughout all of Earth’s history, thus ruling the world through all time with their iron fists of telekinetic death!

Call me up when you need the script for your sequel written, Mr. Johnson. We’ve got some great possibilities here.

I saw Looper with the Evil Genius and Mrs. Evil Genius. All this time travel talk aside, the movie simply didn’t hold our interest. Despite a lot of running around and explosions and shooting adorable four year olds, it was boring. This was a big disappointment for the Evil Genius, who’s been writing all about Rian Johnson this month.

For me, paradoxically, this showed an improvement in Johnson’s work. His first movie, Brick, I couldn’t even sit through, and his second, The Brothers Bloom, I loathed every frame of with the fire of a thousand suns. Looper I found to be merely a dull, confusing mess.

Thus making Looper, in the final analysis, a movie both fans and detractors of Johnson’s work can agree on.

Ha! Bet you didn’t think this would end on such a positive note, did you?

Now go rent La Jetée.

On the plus side, I now understand what you were trying to say in re: Los Cronocrimenes and how the time loop was non-paradoxical. It is an interesting point of view and I like it. I’m not sure it’s any more sensible than what I was trying to elucidate but I like it and finally understand.

So I am not reading the Looper part of your review because I haven’t seen it yet. But the “many worlds” view of time travel is not at all magicky, and makes much more sense than assuming there is one consistent past, present and future for everything, everywhere, “everywhen” in the universe. Frankly, I would argue the assumption of paradox is the result of lazy thinking about time travel. (I’m going to stipulate a reality where I, as an individual, can take a unique path through this dimension of time–e.g., “the past” is actually in my future–but where everything else in the universe follows a static, linear path. This is not very compelling.)

I wouldn’t really recommend Charles Yu’s “How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe,” as I don’t think it really works and it gets kind of boring for dystopian black comedy. But it’s a nice demonstration of the extent to which the many worlds interpretation dispenses with all of these time travel paradoxes, and in many ways, becomes the only rational way to think about time travel at all.

I have read Yu and I appreciate multiple universes as no-more magicky than time travel but the time travel in Looper is still a total clusterfuck.

Basically either time is linear and the future is built on the past or not. You can’t have it both ways in the same story.

Agree! Saw looper last night. Hated the lazy science. Your argument here was the same one I exclaimed to my friend afterwards who liked the movie and took no issue with its irrationality.

The thing about multiple universes is that it is merely a nice sounding theory, with ZERO evidence to support it. There are indeed many theories suggesting the existence of infinite universes. Smart peoples like Brian Greene have written entire books on the subject (and his is very interesting). But the key takeaway is that, while these smart physicists really like these infininte universes, and they like the mathematics which, if correct, demand their existence, there is NO PROOF for any of them yet. There isn’t even any way to test the theories yet. They are purely notional.

So when people go around saying that multiple universes just “seem” really likely, and that furthermore they “seem” really likely in connection to time travel, I don’t know what the hell they’re on about. I mean, so what? You think multiple universes resolve all paradoxes of time travel? Good for you. You have just erased anything interesting about time travel.

In fact, if your solution to time travel is to say that you are in fact going to an alternate reality, then you’re not even talking about time travel anymore. Now you’re talking about an “alternate universe machine” which takes you to some time in some universe where what you do is what you always did, where you’re not “changing” your own future, you’re simply living in a relative past time of a reality where a different future than the one you came from will come to pass.

So. My outrage aside, there’s no reason all of that can’t be the basis for good stories. But don’t tell me that multiple universes aren’t magic until you have even one piece of evidence to suggest otherwise.

Meanwhile, time travel itsef is, of course, entirely magical. So these arguments are ultimately insane. But they sure rile me up!

Mr. Jason Kohn continued this conversation off-blog with me. Thought I’d reprint it here for those many, many people wondering what came next in the endless time travel discussion:

Jason:

Huh. So stipulating magical time travel is OK, but stipulating it in a way that uses internally consistent logic is uninteresting. Better to imagine a set of inherently contradictory rules, imagine a character trying to fulfill a coherent narrative within those rules, and then point out how the story is illogical. That does sound interesting!

I’m not arguing that the many worlds interpretation of quantum physics is “true.” It’s an interesting thought experiment. Like time travel. Or string theory. But it provides a useful way to think and write about time travel if you prefer internal consistency over cherry-picking when to apply rules of logic and when to suspend them. If you like the cherry-picking more, or if you like the stories that spring from cherry-picking more, that’s fine. (Who among us doesn’t have a warm place in his heart for Time Rider: The Adventure of Lyle Swan?) But let’s not pretend this stand is based on some kind of empiricism. You simply like that flavor of magical thinking better.

Along those lines, I have to point out that your claim “you’re not even talking about time travel anymore” doesn’t make much sense. What you’re really saying is “you’re not talking about time in the way I choose to define it, even though I concede that this view of time makes no sense in the context of time travel.” It’s like arguing that if I can’t show ice-breakers pushing their way through giant oceans of cheese, then it’s not even a moon movie, dammit! (Which is, of course, sadly true.)

Supreme Being:

You’re making your point without explaining what you mean. Why am I cherry picking anything? What am I cherry picking?

My argument is very simple. I’m simply saying that if there is a time machine, and if it merely transports you outside of time and into another time, without also going to some other universe or reality, then if you go to the past, you will have always gone to the past. How is that not logical? What’s not logical is saying that as soon as the traveler goes to the past, the future he left is somehow ‘wiped out’ for everyone living there, and now he can ‘change’ things so that a new future unfolds. Well if that happens, what happens to all those people currently in the future? Do they wink out of existence? If you, me and the Evil Genius are in a room, and the Evil Genius gets in a time machine, goes back and kills you, do I just watch you vanish into thin air the moment the Evil Genius goes back? I think that’s nonsensical. What’s in the past was always in the past. That is my logic. I can’t say it more simply. That’s it. Do you not experience the world this way? Does the past wiggle around in your experience? I doubt it. I’m trying to imagine a fiction where yes, there is time travel, and where NOTHING ELSE MAGICAL HAPPENS. That, to me, is a particularly interesting thought experiment.

You seem to be saying that by my allowing time travel, I’ve allowed one magical element to exist, so that by not also allowing every other magical element to also exist, I am now cherry picking.

I think everyone gets this idea that the past has already happened. This is why, if you don’t want to just skip over that, smart people need to start inventing shit like other universes and alternate timelines to allow themselves to 1) have characters able to change the past, and 2) have a science-y sounding reason to allow it.

I’m fine with people using that stuff–changing the past is the major reason to tell time travel stories–but I think it’s crazy to say it’s somehow “likely” that it’s real. It also requires that in any story, whatever theory you use, you use it consistently. Simply invoking “multiple universes” doesn’t mean you’ve just created an internally consistent story. You either make up rules and abide by them or you don’t, no matter your verison of time travel.

When you see Looper you will see a story that just throws every kind of time travel into a blender and renders it meaningless.

And I’m curious why it’s still time travel if you’ve gone to another universe. You can call it time travel. But are you saying that universe also has a certain future and that by going into its past you’re changing it? Or are you just acting in this past as by definition you’ve always acted? Where are you ‘changing’ the past, in other words? If you’re merely traveling between the infinitude of worlds, each containing its own timelime, how are you changing anything?

Jason:

Well, starting at the very bottom here, you’re changing things for YOU. So based on whatever decisions you make or free will you exercise, the future AS YOU EXPERIENCE IT will be different as a result of those choices.

What I’d argue is logically inconsistent is stipulating one actor for whom time is fluid and malleable, but requiring that every other person and thing and electron in the universe remain bound to a static and unchangeable timeline. There is an inherent contradiction there. If time exists as this static thing but I can go back and visit it, then I’ve ALWAYS gone back and visited it and everything that happens has always happened. If it’s possible for me to go back in time and change things, then according to that view of time, things must necessarily already be changed in the place I’m coming from.

This is what I mean by cherry picking. For the purposes of my story, I’m going to imagine a hero who can go back in time and change things for everybody, even though according to the way I’m defining time, things would already be changed. If I’ve decided that time is this external, immutable thing, then there can be no hero, no time travel, no story. The entire adventure would be the equivalent to a positron and electron randomly popping into existence and then slamming into each other and popping out again. If it existed at all, it would, by necessity according to the rules of time we’re stipulating, have zero effect on anything or anyone.

The only way time travel stories make sense is if an individual is creating the future in his or her present, wherever in time/space that present happens to be taking place. This, almost by default, leads to many worlds theory—or at least, a “many timelines” theory, which is essentially the same thing. If one individual can experience two different futures (the one before he took some action in the past and the one after), then time must be understood as something experienced relative to the observer, not some eternal, immutable thing that exists “outside” of all observers and in the same way for all observers. So again, cherry-picking. I can either imagine an actor who can go back in the past and affect the future, or I can define time as one singular thing shared by everybody and everything. I can’t have both.

The many worlds theory is convenient when thinking about this stuff, because it allows you to imagine the future both as something that already exists and as something that’s determined by actions in the present. In this view, I can imagine I am constantly creating the future, relative to myself, at every moment I exist—and so is everybody and everything else. So whether I make a decision that alters the future right now, or whether I use my time machine to go back 50 years and make some decision then, I will still proceed along the path that leads me to the future I am creating for myself. My future entails going back 50 years, taking some kind of action, seeing the results of that action. The old “future”—where I did not take that action—doesn’t “disappear,” it’s just not MY future, and it never was.

Maybe think about it like this: I’m standing in the lab with my assistant, Jane, at a time we’ll call 2012-A, getting ready to jump into my time machine and go back 60 years and kill Adolph Hitler. In MY future, I go to some place called “1942-A” (the 1942 that Jane and I share), and kill Hitler. I then get back in my time machine, where I proceed to some new place called “2012-B”—a world where Hitler was killed 60 years ago, which is very different than the world I left. (It SHOULD be different—it’s an entirely different reality. Because that’s what we’re talking about when we’re talking about changing time: creating a new reality.) So meanwhile, we can imagine Jane back in 2012-A. Jane’s future entails waving goodbye to me and continuing to exist in her own “2012” where Hitler was not, in fact, killed. Because Jane’s reality is Jane’s reality, and my reality is mine. Maybe there’s some version of Jane in 2012-B, and maybe there’s some version of me in Jane’s future 2012-A. But the Jane I meet ain’t Jane, and the me she meets ain’t me. The “present” we experience are now two very different things.

Whether you call these different universes or different timelines or different realities, it all boils down to the same thing, and IMO, is a much more rational way to think about time: if I can go back in time and change “the future,” I am changing MY future. If going back in time means changing everybody’s future, then I already did, or never did.

SB:

Starting at the top. The one person for whom time is malleable is the one using the time machine. But anyone can use it. We’re not talking about a strange individual with superpowers. This hero goes back in time, but what I’ve been getting at is that he doesn’t “change” anything. He isn’t changing all time for everyone, nor for himself. He is merely doing whatever it is he’s doing. Now, as it happens, or at least as I’m arguing, this hero can’t do anything he didn’t “already do.” If he encounters an earlier version of himself, he will of course remember that time when he was that younger self and he met his older self coming back to him in a time machine. And of course from the perspective of the older self, he will have exactly the same conversation he recalls having the other half of long ago.

Now you’re saying (I think) that this kills any possibility of story or drama. I disagree. Assuming this reality that I’ve argued, where if someone comes back from a future, then that future exists as much as the past does, then free will as we generally conceive of it can’t exist. This is what kills the drama for you, yes? But consider that free will is a dodgy proposition as it is. There are strong arguments against it currently existing. But whether or not we have it, the important thing is that we FEEL like we do.

In this time travel scenario where you only do what you already did, where there is no free will–you STILL feel that you have free will. You can’t help but feel that you are the author of your actions and that you are choosing to do what you’re doing. So for the purposes of a hero going back in time, a hero we follow, this hero feels like he’s deciding what to do. He still struggles. There is still drama. Look at The Terminator. This is exactly the set-up. It’s just that this fact of inevitability isn’t the point of the movie. John Connor is alive to send back Reese. So of course Sarah lives. The terminator has to be sent back. His hand and CPU will necessarily survive as the basis for all of Skynet to be created. All of this already happened. Nevertheless, we have drama.

You’re right that for a story where one actually changes the past, some kind of alternate timelines are required, and that each person is altering their own future. But there are some things that have always bothered me about this.

I get hung up on the person left behind. When you leave 2012-A, Jane just watches you go, and that’s it. You invented a time machine, invited Jane over to watch you use it, and then you vanish forever. The end. This strikes me as bizarre, and is why I refer to such a machine as a sort of universe hopper rather than a time machine. At least from Jane’s perspective. But I guess as far as stories are concerned, we’re not worried about the people not in the time machine.

(I just wrote this other long chunk, but it’s late and I’ve stumbled into something more confusing than I thought. I’ll write it up tomorrow, but two things in the meantime: don’t you mean you travel back to 1942-B? As soon as you arrive in a past in which you weren’t previously, surely that is the new timeline/universe, right?

And also, there must be situations where you travel back in time, change something minor, and return to your lab to find Jane waiting for you, a Jane who saw you leave in your time machine. Which means…you can seemingly change the past, even though you’re really in a new timeline, and have only really done what you always do in the past of this particular timeline? And now my brain is tired…)

Jason:

So I intend to respond to this, but it will require some thought and writing. Short answer to your main point: yes, as long as you are telling a kind of “closed loop” time travel story, you should be able to do it even in a world where time is understood as a single, monolithic shared experience. Which is why TimeRider is clearly the epitome of intelligent time travel movies.

http://www.imdb.com/video/screenplay/vi2163671321/

SB:

I am deeply embarassed to admit that I’ve never actually watched Time Rider. That trailer is amazing. But it’s not available on netflix! What the fuck!

I haven’t given you time to respond yet, but in thinking on this further, I see your point more.

So let’s say you leave Jane and go back to whenever. Jane, in the timeline you left, never sees you again. Oh well, too bad for Jane. But as you say, we’re concerned with you, the time traveler. You return to the spot you left from and a different Jane is there waiting for you. But let’s say you only went back a year or so and didn’t change anything notable (you breathed, you killed some microbes, you rearranged some atoms), so in that sense, as far as Jane is concerned, she saw you leave–but wait, she didn’t see you leave. She saw a different you leave. The one she saw leave never came back; he went to another timeline. The you who returns to her came from a different timeline, but since so little was changed, it seems to her as though nothing at all is different. She lives in a world where you were in the past in a time machine, and where you have just returned to her. As far as she can tell, you were always in the past. But for you, that’s not so. You came from a timeline in which you weren’t in the past, and have returned to a future where you were in the past, and changed whatever you changed. So there we are, you can go back and change things.

And I suppose this eliminates all paradoxes as well. You can go back and kill your parents before you were born. You then return to a future where you never existed and no one knows you. Oops. You could even kill yourself. Then go to the future and surprise the fuck out of everyone by still being alive. You can do all of this because the you that is traveling is from a different universe. If you’re from a different ‘timeline,’ whatever that exactly means, this all seems a little more suspect, in the sense that you’re killing potential yous while still existing as one.

But isn’s this all exactly the logical inconsistency you brought up in the first place? Where one actor, the time traveler, is going around to different timelines, and for himself experiencing and effecting the changing of events, while everyone else in those timelines experiences time as immutable? For all of them, the traveler is always in the past doing what he does.

Jason:

So I think to mess around with the implications of the many worlds theory on time and time travel, it helps to step back and make sure we agree on what we mean. So recall that the whole idea here is that this thought experiment called “many worlds” is supposed to solve this vexing aspect of quantum mechanics, whereby under the standard Copenhagen interpretation of quantum physics, the basic building blocks of matter have this tendency to not exist in any definite state until something observes them. So according to this interpretation of quantum mechanics, if you could imagine looking very, very closely at the smallest scale of the universe without officially “observing” it, all you’d see is this frothy mix of potential states, until something causes those very tiny things decide exactly where the hell they are. You know all this.

I know I’ve always felt (and many physicists have felt, and maybe you have too) that there is something just kind of off about this way of looking at things, as it seems to make a whole lot of the universe depend upon our being around to observe it into any kind of specific existence, or at least SOMETHING’S being around to observe it. The many worlds interpretation of quantum theory dispenses with this kind of narcissistic view of reality by postulating that, rather than a quantum object not existing in any definite state until observed, it actually exists in ALL possible states, with each state existing in a different universe within a much larger “multiverse.” And so the act of observing an electron isn’t the act of forcing the electron to choose one state, it’s rather the act of the observer snapping to one specific universe where the electron has one specific state, in an infinite and constantly expanding multiverse of all possible states for all possible electrons.

So to extrapolate this from the quantum level to the macro level and apply it to time travel, the idea would be that at any moment, for any observer, all possible futures are “real” and actually exist. And our progression into one possible universe/future or another presumably is governed by the same laws of probability governing the likelihood of locating a given electron in a given place.

Say I pack up my entire life and get in my car and drive to the end of the block, and flip a coin on whether to turn right or left and see where my life takes me. This single choice splits my reality off into two immediate possible alternate universes, and to a potentially infinite number of future universes that proceed from that split. In 50 percent of all possible futures/universes, I turned right at that intersection, and in another 50 percent I went left. All of those futures “exist.” But as “me”— a specific consciousness associated with the one universe I’m currently inhabiting—I will progress in just one of them. Even though some “me” that’s almost me but not quite will progress in all others. (And will become less and less similar to me the farther our paths diverge.) This process will then repeat itself at every possible inflection point, maybe infinitely, for me and for every other person in the universe. (Again, you probably know all this stuff. Just making sure we’re on the same page.)

So time travel. If we imagine the multiverse described by the many worlds interpretation, we have to accept that every possible thing that could have happened did happen, and every possible thing that can happen will happen, in some universe or other. And this then becomes a really convenient way to think about time travel, because it allows you to think of both the past and the future as objective and immutable things that have already happened, but also to allow for free will without paradox—characters can make decisions that result in different futures (and different pasts).

So going back to the example with me and Jane in the laboratory in 2012-A. You’re right, when I go back to 1942, it MIGHT be 1942-A, the 1942 in the past that Jane and I both share. Assuming that we share a past where I went back to 1942. But it could also be a different 1942. And yes, there are certainly possible futures/universes where Jane waves goodbye to me and never sees me again. And there would also be possible futures/universes where I come back and we do see each other again. Is it the same Jane and the same me? Yes in one possible universe, no in the others. This again, assuming that everything that can happen did happen, and that all of these potential outcomes are governed by probability, there are going to be a large number of universes where all of this went down mostly the same except with slight differences, and a smaller number of universes where it all went down radically differently. If I went back in time and wanted to find my exact Jane that I left back in 2012, would I be able to? I dunno. I guess it depends on how sophisticated my time machine/universe-hopping machine was and how much time I was willing to invest in figuring it out, versus being satisfied with somebody who’s like 99.99999% of the Jane I left behind. Maybe that would make a nice love story.

SB:

I think we are on the same page in terms of the many worlds theory. I understand it as being about Schroedinger’s equations, that when extended beyond things like electrons to rather large things like people, they don’t seem to make any sense given that we don’t observe probabilities, we observe definite things. The Copenhagen interpretation glosses over that by saying we observers collapse Schroedingers’s probability waves. But Schroedinger never said anything about collapsing waves. He came up with his cat to show just how silly an idea it was. Everett’s idea was to take Schroedinger’s equations at face value, and for him this led to a situation where, for example, a particle that has a probability of being at a number of different locations is in fact at all of them, where each one is in its own unique and equally real universe. So there we are.

Time travel can certainly take advantage of such ideas of this to create situations where the past is seemingly altered. But when I think about this, it still feels too easy, or too much like the real issue of time travel is somehow being skipped over. And as I said at the end of my prior note, there’s still this fact of time only having been altered for the traveler, whereas for everyone else, whatever that traveler did in their past, he always did. If the traveler then said, “No, really, I changed the past in this, my time machine. Here, I’ll do it again,” and then took off in his time machine to the past, he would vanish for all time, because of course by again going to the past, he just took off into another alternate universe. I guess it all just feels messy somehow.

I realize the idea that time is a fixed, immutable thing is called into question by the probabilities that govern everything making up the universe. But I’m still drawn to the idea of allowing for the impossibility of a time machine, and then adding nothing else. Of saying, this machine can take you through time, and that’s all it can do. And then asking, based on how we currently experience reality, what the logical repurcussions of that would be.

They would be that the past already happened and it happened for everyone. This is how we experience the world. If a traveler came from the future, then the future must also have, in a sense, happened. Free will would seem mighty dubious. And any attempt to change the past to alter the future would be futile no matter how much it felt as though you were doing exactly what you wanted to do. This creates quite a restrictive atomosphere for writing stories, I realize. But there’s something powerful about this kind of world. Maybe I like it as a metaphor for human existence: we can struggle all we want to change fate, but we’re going to die no matter what. Because I’m cheerful like that.

Time crimes and 12 monkeys are both great examples of a one timeline theory where there’s seemingly no free will and all decisions lead to an exact loop free of any paradox. However I think the more realistic time travel premis is indeed the ‘messy’ multi universe version. A perfect example in movie form is Primer (2004). Probably my favorite time travel movie. It depicts the confusing messiness of time travel in the most interesting and plausible way. I believe if it were at all possible, it would work it this manner. Where anything you do doesn’t cause any sort of paradox, instead the timelines continue to split and like you said, get messy.

Well that was fun to read first thing in the morning.

I guess I think (have been convinced) that travel into alternate universes, even if they involve shifting through time, isn’t really time travel in any important way. If your goal, as in your example, is to kill Hitler—and you have this ‘time/universe machine’, there is no point in going back in time. You just go straight to the (one of an ∞) universes in which Hitler got iced.

You can go back and ‘try to change the past’ but that’s a stupid and pointless thing to do if every possibility not only exists, but exists in an ∞ number of variations. Plus, you’d have to live a variation of your life over again as an older man AND ALSO there’s this younger you around. Awkward, right?

I’ve actually been (not really) working on a novel in which the premise is a character can travel through universes in search of the perfect “him”, but he quickly finds that identity without experience is traumatic. He can be super wealthy, for example, but if he is just super wealthy without the experience of becoming so, he is disconnected, etc. He also quickly discovers that finding his way back to a world in which he recognizes himself is impossible (for technical reasons). I will not tell you how it ends.

The ends.

Well, I don’t think the idea of time travel per se is eroded. It’s more the idea of reality (including time) as any kind of solid, universal experience that gets eroded. I’m OK with that partly because I find it to be a more plausible and logically consistent way of thinking about time, but also because I think it opens up a lot of new and weirder and more interesting questions than the ones traditionally posed in time travel stories.

So, I went to see Looper after work yesterday and it was fucking awesome!

Well, not Looper, that was every bit a disappointing mess. If anything, it was even dumber and lazier than I had been expecting going in, as well as being so thoroughly unengaging that I know without a doubt I would have turned it off had I been watching it at home.

As it was, I was sufficiently bored with proceedings that I decided to get up and take a bathroom break about 3/4rs of the way through, mostly just to stretch my legs. As I wandered out of theatre 14 and headed to take a piss, I happened to look up as the LED marquee for theatre 16 flashed, “LAWRENCE OF” and I stopped dead in my tracks, thinking, there’s only one way that ends, but WTF would that be playing on a random Thursday night at some multiplex in Irvine, CA … “ARABIA”

The fuck? Lawrence of Arabia is playing here? Tonight?

So, naturally, I walked into theatre 16, still in disbelief, to find that the motherfucking overture was *just* finishing. That friends, is serendipity.

Now, in the perfect story, I would have pinched myself, sat my ass down and never thought twice about forgetting about Looper completely. Unfortunately for the perfect story, I had gone to see Looper with Therm and I felt bad about leaving him in the other theatre wondering where the hell I had gone.

So, I went back to 14, disinterestedly watched the last 20 or so minutes of Looper and THEN went to theatre 16, getting to Arabia just in time to join the Man who broke the Bank in Monte Carlo and enjoyed the fuck out of one of the greatest films ever made.

Somewhere along the way, I figured out that I had totally missed the fact that the showing was a special 50th Anniversary one night event that I had stumbled onto totally by chance.

So … so long and thanks for the memories, Looper, you were pretty much shit in every way (with the most notable exception of the kid who played the young Rainmaker … holy crap that kid was great) but you’ll always remind me of Lawrence of Arabia, so you’ve got that going for you …

damn. i wish my screening of Looper had ended with Lawrence of Arabia.

best way to see Looper ever

Looper handles time travel in a way that’s logically inconsistent, and, to be perfectly honest, I think you’re being overly harsh on Time Cop.

I’m mildly amused that it gets such glowing reviews (94% on RT) which use adjectives like clever, brilliant, and thought-provoking.

To say that the movie is overrated is an understatement. With that being said, I did enjoy watching Looper. I just had to turn my brain off 15 minutes into it.

P.S. You forgot to mention the movie Millennium. How? ;)

Sweet jeebus. I’ve never even heard of Millenium! But it sounds almost as good as Time Rider. Clearly I need to bone up on my bad time travel movies.

I’ve put some thought into making more sense of the time travel in Looper. Here’s what I came up with:

The Green and Yellow Timelines are a closed time loop.

Green Timeline (shown in movie as the timeline Old Joe is from):

A) In 2044, Young Joe succeeds in killing Old Joe from Yellow Timeline.

B) Cid becomes the Rainmaker due to his burning desire for power.

C) Young Joe grows old, and meets Yoko, who is killed in 2074.

D) He travels back to 2044 (Yellow Timeline) to kill Cid before he becomes the Rainmaker.

Yellow Timeline (where the movie takes place):

A) In 2044, Young Joe fails to kill Old Joe from Green Timeline.

From here we either continue with the Yellow Timeline, or the Red Timeline:

Yellow Timeline (loop continues, shown in movie as a future possibility):

B) Old Joe accidentally kills Sarah, while allowing Cid to escape. He realizes what he’s done and kills himself (Or disappears. Who knows?).

C) Cid becomes the Rainmaker due to his burning desire for revenge.

D) Young Joe grows old. He purposely avoids meeting Yoko (Or doesn’t. Who knows?).

E) The Rainmaker sends all Loopers back to 2044 (Green Timeline) to be executed.

Red Timeline (loop broken, the ending of the movie):

B) Young Joe kills himself to prevent Old Joe from killing Sarah.

C) Everyone lives happily ever after (except for both Joes, of course).

The Red timeline happens only once. It is not repeated.

It’s easier to swallow if you imagine that Green and Yellow repeat infinitely, until (for whatever reason… The power of Love?) Young Joe chooses to break the closed time loop.

There is absolutely no explanation to that covers the obvious paradoxes, but we’re not supposed to think about them (sigh).

To clarify: If Young Joe in the Green Timeline would have looked at the arm of the Old Joe he had killed, he would have seen the scar of the word “Beatrix”.

We never saw him look, so that’s one (of many) missed opportunities.

I think we can somewhat resolve the existence of the paradoxes present in the movie if the following is true in the Looper universe:

Paradoxes are allowed to occur if their existence breaks closed time loops.

So, if we imagine a Universe that is hostile to closed time loops, but not necessarily hostile to paradoxes, then the movie suddenly becomes self-consistent.

This is (probably) the exact opposite rule of the universe we live in (Novikov self-consistency principle), but whatever. A movie only needs to be self-consistent.

By requiring a Universe with (probably) fundamentally different rules than ours, am I putting more thought into this than the writer did?

I think the main thinking the writer did was, what do I want to happen now? And then that’s what happened.

I think your mapping of timelines makes clear the point I made to begin: that Looper features every sort of theory of time travel all jumbled up together incoherently.

read The Man Who Folded Himself by David Gerrold, best time-travel book ever. one of the few that actually makes any real sense.

looks like a cool book. i’ll check it out.

I just saw Looper last night, and as someone who tends to overanalyze time travel movies and usually ruin the cinematic experience for myself by pointing out all of the flaws, I found this movie to be logically nonsensical but narratively highly engaging. I think this is a high-quality piece of film-making, in all respects other than time travel rule consistency, and I forced myself to overlook them enough to just go along for the movie ride. I came across this blog, and I must say, you put forth some good points about these bent or broken rules, but you have so many other problems with the movie that are simply unreasonable (in my opinion). You didn’t like Brick either, so I’m just going to chalk this up to a strong difference of opinion (Brick is fantastic) and appreciation of style. However, I will say that Looper would have been much better for me if it had ended properly, i.e., when young Joe shoots himself, time reverts back to the moment he is going to shoot Old Joe in the field, and he does, revealing the “loop” to be a neverending alternation between two timelines that cannot be reconciled (in the situation where Young Joe kills Old Joe, another random looper killed Cid’s mom). That would have been okay for me.

it could indeed be an issue with style, at least to some degree. there are many who liked Looper, just as many liked Brick and Brothers Bloom. although if you had to “force” yourself to get over the problems with the movie, that seems not to say too much in its favor. what i like is for a movie in one way or another to transport me, without my having to force myself to do anything. in this case, it failed to do anything, logically or emotionally.

Hey Frank. Glad you were engaged by Looper. If you dig back in the archives here you’ll find that while SB hated Brick, I’m a huge fan of that film. Alas, I agreed with him about Looper.

Not sure about your proposed ending for the film. The time travel was so wishy-washy I’m not sure anything would have really made logical sense. Story sense, maybe.

Thank you for this take on Looper. I agree completely. I found the movie completely stupid beyond belief. I’d be inclined to find the world of He-Man: Masters of the Universe much more plausible than in Loopers. Movie makes next to zero sense. I can’t even express how distraught I am over how the vast majority of movie reviews claim this movie as some sort of intelligent science fiction movie. Really. I just can’t comrphend it. Like to the point that I don’t even know if I’m a human being or not. I don’t understand how a single person who has seen more than 5 movies and is over the age of 12 could find the world of Looper reasonable, or the movie intelligent, at all.

I thoroughly enjoyed reading your analysis. Will probably enjoy the movie, too. Most of the time I get caught up in the action and just absorb anything they throw at me.

Anyway, this reminded me of a book I read long ago that didn’t deal so much with the time paradoxes / fate / free will etc. but more the place aspect of time travel. I mean: assuming you can travel in time, you will also need to travel in place to a specific place in the universe, otherwise you will end up -literally- in the middle of nowhere…

In the book the characters accidentally travel a short distance in time but remain in the same place. Because earth moves through space, they end up hundreds of km away and tens of metres above ground. One of the characters actually needs to be cut loose from a tree because he and his clothes are so intertwined with the branches – quite hilarious. Some locals at first assume he grew from the tree which is an ancient sacred place and don’t want to free him. Later, some scientists explain that in order to travel through time and remain in the same place on earth the target place also needs to be calculated precisely. and of course the mechanism to travel through time needs to support teleportation as well.

I don’t know the name of the book, not that it matters much, it was a short youth book. the characters travel home from where they ended up, get the explanation and that pretty much concludes the story;

There aren’t many stories that I know of that deal with place travel and questions of where you end up. Terminator 2 does so, if I remember correctly by showing a fence with a gaping hole in it. Apparently our terminator friend wound up right in the middle of it – he was lucky to be above ground, I guess. But you need to do something about the existing matter at the destination, either destroy it, move it out of the way, or a swap.. And how do you determine what matter to move with you? everything that touches your skin including the lady you just saved from an evil monster? More probably a sphere from which everything is transported to the target place. In that case everyone around should be extra careful not to lose any limbs.

Fixed portals can fix those issues: with a flat surface portal, you just push the existing matter away and leave a less dense space behind you..

Aaaaaah, Hope I can watch the movie now without all this boucing through my head.

I’ve thought about the ‘where’ aspect of time travel too. It supposes a lot on its own. It assumes that while traveling through time, you somehow ‘dis-attach’ from the world. I don’t know if that makes any sense. Although that’s certainly a question to consider–where are you when you’re traveling through time? And then if you do suppose that you are somehow ‘removed’ from space while time zips past, there’s a lot more to consider than the Earth’s orbit. What about the galaxy itself? It’s moving too. In fact every object in the universe is speeding away from every other object. So to even suggest that your time machine separates you from wherever you are on Earth opens another vast can of worms. Which is to say, be careful when you next watch a time travel movie…

This is a fucking great article. Came real late to the Looper party and what a terrible mess it was.

This is the best review I’ve read on the Internet on the topic of time travel in media and Looper specifically. I like that you brought up the importance of being consistent on the treatment of time travel as a bare minimum. I.e., if the movie can’t even keep to it’s on rules, it’s a pile of poo.

Past that there no reason to add additional comments about Looper. It fails the pile of poo test as your article points out with nice analysis and solid logic.

“The Pile of Poo Test.” Invented, I believe, by Socrates? Certainly an ancient measure of excellence or lack thereof.

I can’t get into the discussion of free will, many worlds and time travel–I just don’t have the time to put my thoughts together in a coherent fashion. But as for topical films, I recommend a short called Hirsute: http://vimeo.com/2381662

I found this review in a search for others who feel that Looper is incredibly stupid. I just saw it listed as one of the best science fiction films of the decade and was totally floored.

Ugh. I hate the movie. It has so many flaws and so many people who just are oblivious to them.

Glad we could help you feel less alone in your entirely correct assessment of the film.

great article. went over my head. I wrote a comment before I was signed in, so it may repeat, but STAR TREK VOYAGE HOME the time-travel one was directed by Nimoy, not Meyer. delete the other one sorry.