Do me a favor, okay? Just click play on the video below and keep reading. You don’t need to watch it. In fact, you shouldn’t watch it. There are no explosions or boobs or giant robot fighting monsters or anything.

This piece of music is Fanfare for the Common Man by Aaron Copland. It is the perfect soundtrack for this edition of Mind Control Double Features because this week we’re watching two films that are all about the search—the fruitless, misdirected, and often surprisingly egocentric search—for that mythical creature: the common man.

What? You were expecting yetis? Maybe next week.

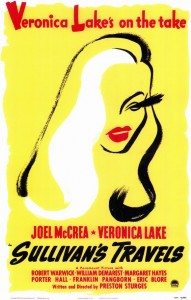

Sullivan’s Travels

If you’re a fan of self-aware films like Being John Malkovich and Holy Motors, and if you think those films are modern and ahead of the curve, then I’d like to introduce you to Mr. Preston Sturges.

If you’re a fan of self-aware films like Being John Malkovich and Holy Motors, and if you think those films are modern and ahead of the curve, then I’d like to introduce you to Mr. Preston Sturges.

This hoopiest of froods dealt out diabolically satirical comedies in the 1940s. That’s right! The goddamned 1940s! That’s so far before you were born, I bet you can’t even count that low. Despite these films being well-seasoned and black & white they’ll still make your head spin. We’re talking about strange and wonderful stories told with real panache: The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek, The Great McGinty, Hail the Conquering Hero, The Lady Eve, Christmas in July, The Palm Beach Story, and, of course, Sullivan’s Travels.

In Sullivan’s Travels, our main character is a director of popular films—much like Sturges was himself. Joel McCrea plays the lead role, John L. Sullivan, as if he were a likable version of a Depression-era James Cameron, which granted is hard to picture. This is a director who makes popcorn fare; fluffy, fun, romps that people enjoy but fail to take seriously.

At the start of this movie, feeling a smidgen grandiose, Sullivan aims to make his Avatar. He’s got his hands on a book about the life of the impoverished. This was a community there was no lack of in 1941.

To the consternation of his producers, Sullivan says this socially important book is going to form the basis for his next film.

To the consternation of his producers, Sullivan says this socially important book is going to form the basis for his next film.

Now Sullivan is a rich, successful, coddled Hollywood wunderkind. He knows bubkis about bums, hobos, or dressing yourself without formally attired personal staff. This his producers point out to him, suggesting that he instead make something a bit, well, sexier. Sullivan won’t back down. He concedes that even an important film like his will need to have sex in it—but if his lack of familiarity with poverty is a problem, he’s got a solution: he’ll cut himself off from his wealth and mingle with the common man.

And that’s the premise of Sullivan’s Travels.

A well-off, self-important artist wants to help the common man by telling the world their story, even though he hasn’t got the foggiest notion of what the unsheltered world feels like. Despite everyone from studio executives on down to his own butler telling him his idea is ghastly, Sullivan does his best to escape the protective embrace of Hollywood and join the company of everyday, hard-luck Joes.

It doesn’t hurt that his first real contact with “actual humanity” comes in the form of the luminous Veronica Lake—even an important film needs sex, right? Lake plays a character who despite being a lead never gets a name. Seriously. She’s just “the girl”—and I don’t think that means Sturges thought little of his leading lady. Did you see the poster up above? I think he’s, instead, making a comment about ego-centrism. He’s a clever man, that Preston Sturges.

It doesn’t hurt that his first real contact with “actual humanity” comes in the form of the luminous Veronica Lake—even an important film needs sex, right? Lake plays a character who despite being a lead never gets a name. Seriously. She’s just “the girl”—and I don’t think that means Sturges thought little of his leading lady. Did you see the poster up above? I think he’s, instead, making a comment about ego-centrism. He’s a clever man, that Preston Sturges.

In any case, The Girl is a failed actress who only wants to head home. She and Sullivan end up teaming up for hijinks that slowly and painfully teach the dilettante director what he thinks he wants to learn.

Sullivan’s Travels is an incredibly funny, insightful, and subversive piece of filmmaking. Sturges is clearly lampooning himself and his community of artists who think they can and should tell the so-called common man a damn thing about their lives. That doing so would be the slightest bit helpful to honest-to-god poor people. (John Ford’s The Grapes of Wrath came out the previous year, in 1940; just sayin’.)

Joel McCrea and Veronica Lake are excellent together but I would be happy watching Veronica Lake clean sink traps during tornado season, so I might not be the most dependable judge there. She’s real purty, like, and all class.

Like most of Sturges’ films, he wrote and directed this picture, making him one of the few true auteurs out there. A Preston Sturges film is indeed a Preston Sturges film. It couldn’t have existed in any form without him.

Like most of Sturges’ films, he wrote and directed this picture, making him one of the few true auteurs out there. A Preston Sturges film is indeed a Preston Sturges film. It couldn’t have existed in any form without him.

I won’t give the whole story of Sullivan’s Travels away, but I will tell you this—in the end, John L. Sullivan decides not to make his self-important film about the common man, which was titled what, you inquire?

It was to be called O Brother, Where Art Thou?

But if you think that Coen Brothers film is our second feature, guess again.

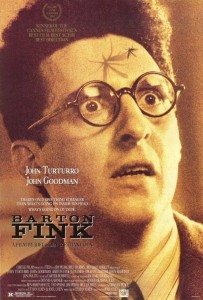

Barton Fink

Speaking of satiric, self-aware films about the search for the common man, which it just so happens we were, I give you Barton Fink.

Speaking of satiric, self-aware films about the search for the common man, which it just so happens we were, I give you Barton Fink.

The Fink is, perhaps, the pinnacle of Coen-ness. The most Coen there is without being cloyingly Coen (like, say, O Brother, Where Art Thou?). It’s a gob-smackingly brilliant dissection of the creative brain. In fact, the whole film, in one sense, takes place inside the squirrelly skull of Barton Fink—a promising New York playwright who prides himself on writing about and for the common man.

None of that artistic, self-important twaddle for Fink, see?; he’s too artistic and self-important for that. No, he’s creating a whole new kind of theater, but first he’ll make some easy dough in Hollywood.

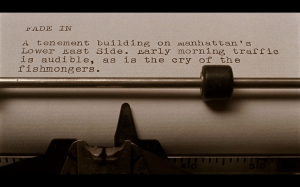

Barton Fink takes place in, you guessed it, 1941. As Fink gets sponged up by the studios and enveloped by his surreally seedy hotel, we get a refraction of the world Sturges lampooned in Sullivan’s Travels—verdant gardens, scintillating swimming pools, and scraping servants.

But Barton Fink is a different sort of fish. Where Sturges’ film seduces you with breezy comedy and then hands you the ticking bomb that is our world—surprise!—the Coen’s movie traps you like flypaper. It is very funny, sure, but in a sickly way. In a way that makes you wonder if your smile is going to be used as evidence against you in a court of law. Because Barton Fink is so not-funny its funny. Or maybe it’s so funny it’s not funny?

We’re only interested in one thing, Bart. Can you tell a story? Can you make us laugh? Can you make us cry? Can you make us want to break out in joyous song? Is that more than one thing? Okay!

Or maybe it’s just going to wrestle you to the ground, like a giant, sweaty, common man, who’s only trying to help.

In the story, Fink—a perfectly cast John Turturro—is given an easy assignment by Jack Lipnick (Michael Lerner), the head of Capitol Studios. He wants Fink to write a wrestling picture for Wallace Beery to star in. It is a by-the-numbers affair and no one expects anything but the standard garbage with some “Barton Fink feeling” sprinkled in. But Fink can’t do it. He flails around inside his head like a buzzing mosquito, lost and disconnected from the blood of the world.

He’s lost touch with his mythical common man, even though his neighbor in the Hotel Earle, Charlie Meadows (John Goodman), sure looks and acts common.

Barton Fink isn’t the kind of film one summarizes, though. It’s a web of symbolism surrounding a wriggling, threatening dream of a story. Kind of like an egg full of baby spiders, I guess. In this case though, the baby spiders are played by fantastic actors in elegantly carved roles, including Judy Davis, Steve Buscemi, Jon Polito, Tony Shalhoub, John Mahoney, and many others.

Is Barton Fink a film noir? A comedy? A horror movie? A satire? Yes. Sure. All of that. It’s something you haven’t seen, unless you’ve seen it, which you will. It’s the story of a well-off, self-important artist who wants to help the common man by telling the world their story, even though he hasn’t got the foggiest notion of what the unsheltered world feels like.

Like Sullivan at the end Sullivan’s Travels, Barton eventually comes to realize something he never suspected about the common man. I’ll let you unwrap that realization for yourself when the time comes.

Until then, let’s raise a toast to the everyday Joe. Or the yeti. Which you’re equally as likely to meet strolling down the avenue.

Though I’ve seen Fink a million times, it’s been years since I watched it. I think I’ll have to check it out again soon.

Have you seen all of those Sturges movies? I don’t think I’ve watched Christmas In July or Palm Beach Story.

I haven’t seen them all. Coincidentally or not, I’ve missed the same two that you have.

I just watched the Palm Beach Story. It’s pretty great. Much better than Great McGinty, which doesn’t really do much for me.

Boxing picture?

The fuck???

Jack Lipnick: Look Bart, barring a preference we’re going to put you on a wrestling picture, Wallace Beery. I say this because they tell me you know the poetry of the streets, so that would rule out westerns, pirate pictures, screwball, Bible, Roman… look, I’m not one of those guys who thinks poetic has got to be fruity. We’re together on that aren’t we? I mean I’m from New York myself, well, Minsk if you want to go all the way back. Which we won’t, if you don’t mind and I ain’t asking. Now people are going to say to you, Wallace Beery, wrestling, it’s a B picture. You tell them: BULLSHIT! We do NOT make B pictures here at Capitol. Let’s put a stop to that rumor RIGHT now!

Relax, Stu. I’ll fix it.

Yeah, you should get on that Zack …

We aim to please.

And, oh yes … Barton Fink is fucking awesome and anyone who has never watched it before should do so immediately …