How many visions of our future are we, the cinema-going public, afforded each year? Let’s say plenty. And of those (plentiful) visions, what number reminds us, callously, tauntingly, that we still do not have our long-promised flying cars? Which vision first promised them, anyway? Was it The Jetsons? Was it The Fifth Element? Was it, by any chance, Blade Runner (1982)?

This is the future liberals want.

In Blade Runner 2049 (2017), the flying cars are back, and their promise is somewhat darker. Repeatedly, we are forced to contemplate what happens when a flying car, cruising high and fast and free, quite suddenly stops flying. Here is a bit of realism. Any future marked by flying cars must also sometimes feature plummeting cars. We cannot and do not desire everything that we imagine our future to offer.

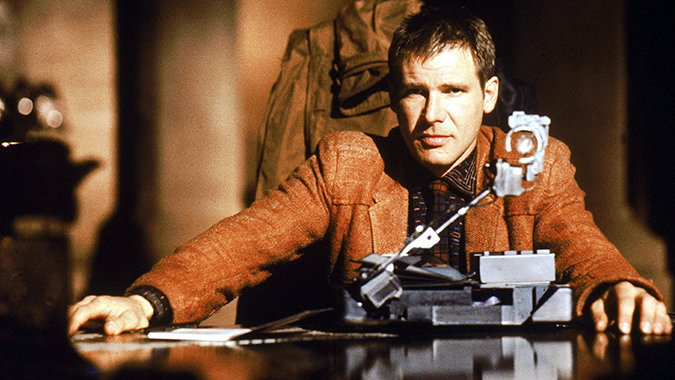

The span between these two iterations of Blade Runner has been very kind. (Thirty years have elapsed for the characters and their world, thirty-five for us and ours.) The original film has, in everything but its sex politics, aged beautifully; its filthy utilitarian aesthetic and bleak tribute to detective noir still scratch every retrofuturistic itch. We’ve grown only more interested in the question of our humanity and its meaning in the face of ever-intensifying simulations thereof. The intervening years and regular definitive-edit upgrades have solidified that film’s place in our hearts.

If I’m a replicant, how come they designed my nose to melt halfway off my face 30 years from now?

Have those years left room in our hearts for the all-new iteration? It devotes itself to worming its way in, and in the process it offers both charms and revulsions.

Where once a towering neon-and-grit Los Angeles pushed mattes and models to their maximum potential, now CGI is deployed with awesome restraint, massively amplifying the city’s scale and detail without ever slipping an inch away from its source’s visual sense. The characters, too, are louder echoes of our beloved, dilapidated originals. Our blade runner, once a human who can’t quite perceive the film’s hints that he’s a replicant, becomes a replicant all too aware of the film’s hints that he could be (half) human. Where the human who kills replicants once fell in love with one, the replicant who kills his own now loves and fails to protect something even less human, a hologram, a well-animated sex toy he can’t even touch.

Can this even more hollow and meaningless shadow of pliable, agency-less femininity somehow reach back through time and give philosophical weight to Sean Young’s classic fantasy rendering of unlimited victimhood? Can it ripen her uncanny-valley cameo in 2049 from CGI monstrosity into perfect intersection of wish fulfillment and terror-by-fraud?

Our new version of Daryl Hannah’s Pris (now Mackenzie Davis’s Mariette) is similarly both destroyed and renewed: she is, as a character, squandered, underutilized, and that vastly worse than before, yet she has evolved from painted toy to scheming revolutionary soldier. Only Rutger Hauer’s Roy Batty is missing — standing in for him is Luv (Sylvia Hoeks), another freakishly Nordic replicant fatale, this time exceeding the proper bounds of its autonomy not to kill its father but to further its father’s vision of a new creation myth, to enable sexual reproduction itself to re-enter the world. Could anything better sum up this transformation of Blade Runner from 2019 to 2049 than the landscape of ruined Vegas, strewn with hundred-feet-tall hollow naked women, twisted into porn poses and painted in dust?

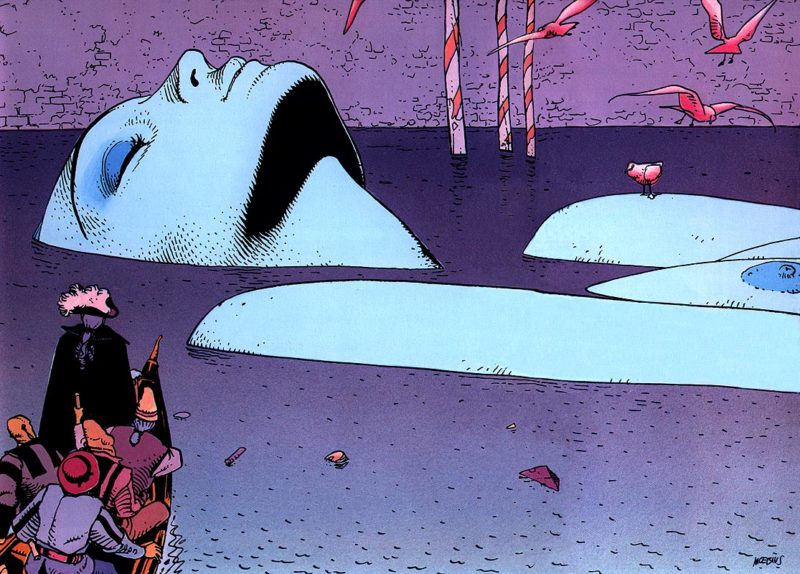

Is Moebius not credited? His estate should sue.

The film is an awesomely rendered, often careful and delicate mess. Such contradiction! Its pace and visual beauty are nearly flawless, yet it is far too long and sometimes, to the eye, twice as big as it needs to be. With a few glaring exceptions near the end, its every story beat is satisfying and sensible, and still practically every scene’s dialogue is a wretched hodge-podge of exposition and sentimentality. Huge dramatic physicalities are sometimes summoned, like John Woo’s doves, for no reason other than to heighten a dramatic state, and like Woo’s doves, we embrace them despite their absurdity. Also, the score is fucking great.

This is a flying car that just took a high-caliber round through the engine block. This is the thrill and terror of the descent, and the long exhale at realizing that there are hidden emergency jumpjets strong enough to pull us out of a head-on collision with the ground. Of course there are. Who would ever design a flying car without them?