The first scene of the David Lynch directed Twin Peaks season two opener is the most magnificently, insanely, absurdly brilliant and confounding scene ever aired on television. No one but Lynch would have dared to do what he did with it. The first season of the show—eight episodes in the spring of ’90—had caught on bigger than anyone expected. The question of who killed Laura Palmer had gripped America like only the soapiest of soapy mysteries ever had before. Twin Peaks was a night-time soap mixed with a police procedural shot through with surrealism, comedy, and terror. It was set in the present in a small woodsy town half-trapped in a dream-version of the ‘50s beneath which boiled a timeless evil. It was both eerily familiar and totally bizarre. Nothing like it had ever been seen on television.

It was the first time a film director as well known for his idiosyncratic style as Lynch had deigned to work in the wasteland that was ‘80s television. That he was riffing on the themes of Blue Velvet, one of the most disturbing movies in then recent memory, made it all the more unlikely. No one knew what to expect.

Lynch had met co-creator Mark Frost working on a number of never-made projects (including a bafflingly strange and wacky comedy called One Saliva Bubble that might have starred Steve Martin (I’ve read it; it would have been grand…or, possibly, terrible)). Frost’s knowledge of TV kept Lynch working within the confines of the medium. At least structurally. Content-wise, not so much.

Uncertain their creation would last past the first season, itself an improbable pick-up for ABC once they’d seen the Lynch’s pilot, Frost made sure they went out with so many cliffhangers they’d have to be renewed. Damn near everyone in Twin Peaks is either killed, almost killed, or kills someone. Audrey is about to be molested by her father at the whorehouse he owns. The mill is on fire. And, worst of all, Cooper is shot in his hotel room by an unseen assailant.

It worked. The show was renewed. This was in late May. Back in those days, not only did we live in small caves, we could only watch TV shows when networks aired them. Madness! It’s a dark age humanity was lucky to survive. For those who’d missed the season on its first run-through, ABC was kind-hearted enough to rerun it over the summer. Twin Peaks fever peaked. People were insane for it. No one in the country ate or drank anything for three straight months but cherry pie and coffee.

And then, four months later, the second season began. Of 22 episodes. More madness! Nowadays we get a ten episode (or so) season followed by—a year’s wait for another ten. A nice long year for thoughtful writers to come up with a season’s worth of story.

Twin Peaks couldn’t have known it at the time, but it was a show built for the modern era of short seasons with one compelling arc driving each of them. Imagine if there’d been a year between seasons of Twin Peaks, and imagine season two was only ten episodes. This is what the show demanded, but that form of television had yet to be invented (we’d have to wait until ’99 and the blessed appearance of The Sopranos for the modern era of TV drama to be ushered in). In those days, dramas ran the length of the TV season, and the season began in September. Don’t have a 22 episode story-arc handy? No worries, you can make it up on the fly.

Murder mysteries weren’t supposed to last as long as Laura Palmer’s. The audience was willing to accept a four month cliffhanger, but the second the show returned they expected an answer. The network insinuated they’d be getting one…soon. Frost was on their side. He felt the show had made a promise it had to fulfill. Lynch disagreed. Vehemently. He felt the show only worked with the mystery forever unsolved. Laura Palmer’s fate was meant to slowly fade into the background as other stories grew deeper and more involving, but without ever fully disappearing. Her unsolved murder was to be the engine that drove the show.

This disagreement, and its resolution in the wrapping up of the Laura mystery in episode nine of the second season, is why Lynch distanced himself from the show for most of the second season. With no more mystery and (almost) no more Lynch, the show collapsed. Twin Peaks worked because of Lynch. Its oddness was Lynch’s oddness. Without him there to oversee it, no one knew what to do. They might have, if only the backbone of the unsolved murder was there to support them. Without it, what was this show?

But back to the season two opener. We’re at peak Peaks. Passions are high. Cliffhangers are hanging. Who’s dead? Who’s alive? Who’s been deflowered by her own father? Will Laura’s killer be revealed? Who the hell shot Cooper? People organized viewing parties. Tensions ran high. Excitement was through the roof.

So how does Lynch open the episode? With Cooper on his back in his room, shot and bleeding, and an old, old, fucking old waiter delivering him a glass of milk, giving him a thumbs up not once, not twice, but three times, not calling a medic, and taking ten minutes to do it. Ten minutes. On television. An unheard of eternity.

Well. Maybe it’s only eight minutes followed by a brief cut to Audrey escaping the clutches of her father—whew!—but then we’re back to Cooper, for another entire scene on his back, this time with a mystical vision of the Giant, who offers him advice and three clues. And, then, finally—cut to commercial. Having answered exactly nothing at all.

Who but Lynch would fuck with his audience on this massive a scale? I don’t know, maybe owing to the modern era of TV it doesn’t seem quite so incredible. But it was at the time. It was slow. It was cinematic, and not ’80s Hollywood cinematic, but European art-film cinematic. Its pace would have fit into Eraserhead perfectly. This simply didn’t happen on television. For that matter, it still doesn’t. You fall asleep watching a 90 minute movie but stay up all night binge-watching nine hours of TV because TV, even today’s best, is designed to keep pulling you along and dropping you into the next scene, and the next, and the next. Lynch doesn’t think this way. He holds your attention by taking his time, and tripping you out.

Even forgetting the extreme level of messing with expectations this opening represents, it is, taken on its own terms, watched in any era, wonderful, strange, and haunting. The weirdness of the Giant’s presence is accomplished like so many of Lynch’s creepiest moments: with lighting. The lights dim and a spotlight shines on the Giant. So simple, so effective.

The rest of the episode covers the needed bases in terms of resolving cliffhangers (with no word on who killed Laura or who shot Cooper), but does it with a style unique to Lynch. There’s horror, slapstick comedy, ominous foreboding, deep emotions—this episode has everything. Take one example: Andy stepping on the board. He’s knocked in the face, and proceeds to waddle around, dumbstruck, for what feels like an hour. And it works. Why? I have no idea. When other directors on the show throw in “weird” stuff and “quirky” moments, it feels obligatory, a reminder, a “Hey you guys! Look how quirky Twin Peaks is!” nudge in the ribs. Their attempts at quirk aren’t half as loopy as Andy waddling, yet they feel twice as forced. Somehow Lynch’s extreme oddness taps into an emotional reality lurking deep in the depths of the human mind. A strange, Lynch-ian reality, to be sure, but neither forced nor fake.

I believe that, as a director, Lynch works magic. Simple as that. You can take apart the components of what he does all you want, it still doesn’t explain why what he does works. How is it a simple, static shot of a staircase and a whirling ceiling fan scares the hell out of us? How is it three grown men dancing and leaping around an office fills us in on a movie’s worth of backstory? How does the dreamiest song ever sung fit so naturally into a backwoods biker bar we don’t even think to question it? How does a shot of an empty room lit by a lone lamp to the clicking of a record player fill us with terror? I don’t think Lynch himself knows the answers. He speaks of ideas coming in dreams, or suddenly, in moments of revelation. He trusts in his visions, just like Cooper, and runs with them.

Regarding the new season of Twin Peaks, discussion on the interwebs sees a lot of people wondering whether it will resemble the show or the movie, Fire Walk With Me. The answer is obvious. It will resemble both Fire Walk With Me and the show—the show Lynch directed. His episodes are of a piece. They are Lynch, through and through. I expect the new series will be the same.

Watching Twin Peaks over the past month for the first time in years, I was struck by how dramatically Lynch’s episodes stand out. He only directed two in the first season, including the pilot, and four in the second season. They comprise the best episodes of the show. Everything he does feels and looks different. They’re the same actors on the same sets with the same crew, and yet in Lynch’s hands there’s an underlying dread, a yearning, a nostalgia for something that never existed, but that haunts us just the same. None of the other directors capture Lynch’s mood. The show maintains a style, but the farther away Lynch strays, the less it functions as anything but strangeness for strangeness’s sake.

Nowhere is Lynch’s inimitable style more blatant than in the show’s final episode. Once Laura’s murder is solved nine episodes into season two, the show falls apart. It feels like everyone working on it is wandering blind, praying for a story, any story, to emerge. The comedy quirks turn sour. The drama is unconvinging. Worst of the lot is James Hurley’s pseudo-noir adventure with that lady and her car and her—

Oh for fuck’s sake! Who cares? It’s no wonder James vanishes from the show after that. He, the character, was too embarassed to stick around.

As the show rolls along, there are good scenes to be found. There are moments. I’m always happy to see David Warner and Dan O’Herlihy (as Eckhardt and Andrew Packard, respectively). And, if you can’t tell already, I love this show to death, so something about the whole vibe of the thing never fails to compel me. But man, the back half of the second season is tough. Too much terrible soap-opera inanity, too little depth, too little fear, too little reality. I’m saying it one more time: Lynch brings to his extreme surrealism an intense emotional reality no one else directing that show is able to achieve. Lynch showing people’s quirks pulls us in. Others doing it pushes us away.

Back to the final episode. Set aside the solid fifteen (wonderful!) minutes wandering around the red room. Look at the Ed/Nadine scene and Lynch’s master shot: with a wide angle lens and his typically meticulous lighting everything we’ve come to know about these characters in the second season changes. No longer is it a sideshow farce about a wacky lady who thinks she’s sixteen. Now it’s painful. It’s wrenching. Not only do we experience the pain of Norma realizing she’ll never have Ed, we at long last see Nadine as a real person. A deeply troubled person, but that’s the point, that’s why we can believe at scene’s end that Ed will stay with her.

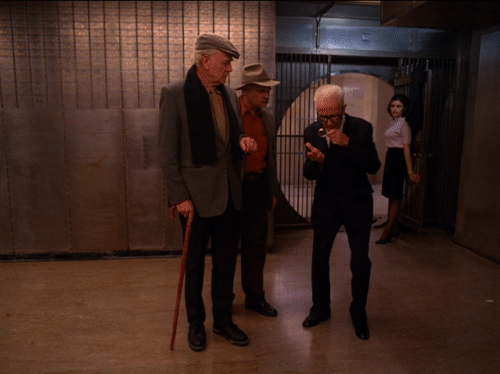

The bank scene is even more extreme. Lynch is back to fucking with us like he did in the season opener, with a slow old man walking back at forth at such length you can’t believe this isn’t a three hour Russian movie from 1963. There’s two ways to pay off a scene so absurdly drawn-out. One, you have no pay off. Always a possibility with Lynch. Or, two, something outrageous happens. Like the bank blowing up.

Finally, the red room, with every dream character in the show, and some real ones besides, returning to taunt Cooper with their curious backwards-speak. Scenes this obscure and protracted rarely show up in movies, let alone network television. With the show already canceled, Lynch figured he could do whatever he wanted with this last episode. What he does is remind us why we loved the show to begin with. For one last hour, everything clicks.

There are many questions out there to be answered by the new series. Knowing Lynch, few of those questions will be given anything like a direct answer. Which is as it should be. Lynch understands something very important about human nature: We want answers. Doesn’t matter if we get them. We’ll only want more. An answer is satisfying for about a minute. A lingering question never grows old. It’ll gnaw on us forever. Lynch is going to give us a lot of Lynch in the new Twin Peaks. I bet when it’s over we’ll only want more.

I love your website, I have been lurking here for a time. I think this here is the best article on TP and Lynch I’ve read the past months (and you must have noticed there are A LOT right now). I agree wholeheartedly with every word and especially liked your conclusion. Twin Peaks season 3 has me psyched like little else ever before it. I think we all need some of Lynch’s magic right now.

We are very fond of people who love our website. Lurk or comment as the mood strikes. And thanks! Yep, there’s lots of Twin Peaks action out there, not all of it enlightening. I’m deeply fascinated at what a late in life, 18 hour movie by David Lynch will look like. I imagine I’ll have something or other to say about it…