There are few actors who consider themselves gods. We should be thankful for that. But there are some who do. For which we should be even more thankful. Because when an actor begins to see himself (it’s always the men, isn’t it?) as the characters he’s playing, and when those characters are saving the woman/child/county/world/universe from evil-doers, self-perceived godhood here in the real world is never far behind. What could be more entertaining?

Having recently made the reasonably poor decision to spend well over two hours of my life watching The Last Samurai, starring Tom Cruise as a man who is, I would have thought it obvious to most, not Japanese, I couldn’t help thinking it would have made far more sense if it starred Kevin Costner. And thinking about Costner’s obvious analogue, Dances with Wolves, for which, to the perplexity of, for example, fans of Stanley Kubrick, Akira Kurosawa, Orson Welles, Alfred Hitchcock, Robert Altman, Sidney Lumet, Fritz Lang, Ingmar Bergman, Otto Preminger, Sam Peckinpah, David Cronenberg, and David Lynch, he (Costner) won a Best Director Oscar, Mel Gibson naturally came to mind, having also won an improbable Oscar, not for his performances in either The Road Warrior or The Beaver, but for directing Braveheart.

These three actors, and these three movies, have, on the one hand, much in common—in each, the star plays a mighty, heroic savior fighting a lost cause to aid a noble people—and yet, intriguingly, their versions of godhood are strikingly different.

Let’s start with the true believer of the old-time religion, a man who’s gone out of his way to impress upon us the nature of his beliefs, religious and otherwise, who went so far as to make The Passion of the Christ, a plot-less, almost narrative-free account of a man (give or take) being tortured to death, with more blood and gore than the Saw movies combined. I saw The Passion of the Christ when it came out, curious how it would play. I watched with jaw on the floor. At the end, numerous people in the theater could be heard to weep. Mel Gibson knew what he was doing. If your religion claims the son of god was tortured to death before coming back to life to redeem the rest of us, you’re going to find a minute-by-minute, bloody, lacerating account of that torture deeply affecting. (Also of note, Gibson’s making a sequel for 2020, The Passion of the Christ: Resurrection, some portion of which follows Jesus’s trials in Hell. No joke. I can’t wait.)

Years before directing Christ, Gibson directed and starred in Braveheart. It was here his personal journey to savior-hood began in earnest.

Gibson plays William Wallace, a Scotsman in the late 13th/early 14th century who leads a rebellion against the English. He is noble, pure, honest, and true, and like all such Jesus-like paragons of virtue, he is captured and killed at story’s end. Like Jesus before him, Wallace doesn’t die peacefully in his sleep. Rather, he’s hung, drawn and quartered—then decapitated.

Unlike many a Hollywood star, Gibson couldn’t have been worried about Braveheart’s lack of a happy ending. Gibson didn’t need Wallace to win. He had something better than momentary, earthly triumph: Death and eternal martyrdom. A perfect fit with Gibson’s religious views, both outer and inner. He was bringing the good word to the people—and winning an Oscar doing it. A decade later, he’d tell the story of the big J in big Hollywood fashion, and become known less for his acting than his off-screen persona as an angry bearded madman and/or prophet.

Kevin Costner is possessed of a far more chill savior complex. He’s never made a spectacle of his specific religious beliefs, whatever they may be, instead cultivating the image of a blue-collar, regular guy who just happened to stumble into acting and directing fame, much to his eternal chagrin. He’s the kind of guy who never claims he’s anything special, but who makes film after film about his being the second coming of Christ, however reluctantly. So, exactly his off-screen persona: A guy who left the common-people to be famous, not because he wanted to, but because we demanded it of him.

In fact, being reborn has defined Costner’s career. He was just starting out when he was cast as the dead friend of a group of aging boomers in The Big Chill. His scenes were cut. So, starting out dead on the cutting room floor, Costner had to work his way up.

And so he did. Like Joan of Arc before him, voices spoke to him, telling him not to lead the French in battle, but to build a baseball diamond in his cornfield. And I mean heck, it’s not like he wanted to build that field of dreams, but how could he say no? Shoeless Joe said he oughtta. So he did. The movie was a huge success.

Next up? Directing. In Dances with Wolves, director/star Costner plays John Dunbar, a Union Army First Lieutenant fighting the good fight in 1863. At the outset, he’s injured. His leg is to be amputated. Death, he concludes, is preferable. Arms spread wide as if to embrace all the sinners of the world, he rides straight at the enemy, Jesus on the horse, a sacrifice to the good lord above.

He’s shot, but, alas, he does not die. Rather, he is reborn at a frontier outpost, way out west in Sioux territory. As we might expect of a white soldier in 1863, Dunbar makes friends with the Sioux, falls in love with the chief’s adopted white daughter, and, after being voted an honorary Sioux named Dances with Wolves, wanders off into the wilderness with his true love, never to be seen again.

No martyr Costner! Unlike Gibson, a religious literalist of fire, blood, and brimstone, Costner’s religion leans toward the metaphorical. His death and rebirth are spiritual not literal. Costner doesn’t want to die to save us. He barely wants to save us in the first place. He just wants to live the good life, the redeemed life, the woke life, if you will (though, please, don’t).

Mind you, Costner doesn’t actually save the Sioux. That cause is so lost even a white man can’t help. He merely aids them with humility and reverence for their mystical ways. The message isn’t that of a white savior, it’s that of a white apologist. Here Costner wishes to represent the modern day Americans who feel kind of lousy about that whole Native American genocide thing, who, if they were alive back in the day, swear they would have appreciated the natives’ nobility, honor, and deep connection to nature in just the way Dunbar does.

Costner is Jesus, yes, but not the kind who dies for the rest of us. He’s a reluctant savior. He makes this clearer still in later films like Waterworld and The Postman. In each, he starts out a loner, only to grudgingly accept that, yes, he’s the one man able to save the world, so by gum he might as well go ahead and do it, just so long as nobody makes a big deal out of it, he’s just a regular guy, remember, and never asked for any of this. Despite which, at the end of The Postman, a golden statue of Costner is unveiled, that we may never forget his commitment to on-time postal delivery.

Notably, Gibson started out playing the kind of characters Costner would develop into. Gibson’s Mad Max is, in retrospect, a Costner-like reluctant hero, a man utterly destroyed, body and soul, who cares for nothing and no one, who yet finds himself helping those in need for one simple reason: No one else is man enough—or god enough—to get the job done.

Gibson, the mad preacher of end times; Costner, the hippie Jesus; and Cruise, the… oh, damn… help me out here… the creator in the flesh, maker of his own reality, god on earth, thwarter of Xenu and his billions of thetans?

Tom Cruise is, like Gibson, a religious literalist, but one of a very different stripe, whose adherence to science fiction author L. Ron Hubbard’s outrageous scam, Scientology, only grows stronger the more its practices are revealed to be abusive and criminal.

Unlike Gibson, Tom Cruise has no dreams of martyrdom. He’s not about to die for anyone else’s sins. He’s not interested in your hero worship if he’s not here to enjoy it, heroically. And forget about reluctance. Scientology assures him he’s earned his godhood. Rising high in the world of Scientology—and none have risen higher than Cruise—is to free oneself of all restraints, and to literally bend the world to one’s desires. Cruise doesn’t need to be convinced to come out of his hiding place to save us. He’s here to lead, and he’s here now.

Hence The Last Samurai, the epitome of the white savior story. It’s been called Dances with Samurai, and reasonably so. On the surface, it’s all but indistinguishable. Look a little closer, and see it’s a very different film. It must be, to comport with Cruise’s unique self-concept.

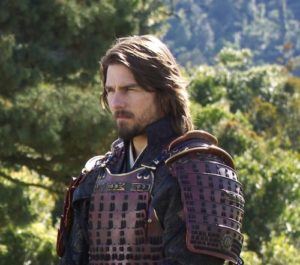

Cruise plays Nathan Algren, a reitred U.S. Army captain known for having served with Custer and slaughtering countless Indians, memories of which haunt his drunken nightmares. He’s recruited to help Japan’s young Emperor in his efforts to westernize backwards Japan. Seems the Emperor has a samurai problem. They’re revolting, and he needs western guidance to shape up his Imperial Army.

Algren is your basic surly American drunk until the first fight against the samurai, when the Imperial Army gets its collective ass kicked. Algren puts up a last-ditch effort so mighty, it inspires the awe and respect of the samurai leader, Katsumoto, who spares Algren’s life and brings him home to his mountain village.

Naturally there’s a woman to fall for, this one the wife of a samurai Algren killed in battle. Algren is living with her and her children, per samurai code. Talk about awkward.

Algren, as evolved an 19th century white man as Costner’s Dunbar, can’t help but fall under the sway of the samurai and their noble, nature-loving, ass-kicking-with-naught-but-sticks-and-swords ways, as we knew he would (because we would have too, damn it! We swear it!). The Emperor is a mere puppet, the Americans are jerks, only Katsumoto fights for something horonable.

But wait—the Emperor is a puppet? Alas! The Emperor is a puppet. Thus, Katsumoto has no master. He must commit Seppuku, as per ancient samurai code.

Unless—hold it a second, is there an American around here willing to both praise the beauty and perfection of the samurai code while yet insisting Katsumoto ignore it to gain greater glory by dying in battle? Yes. Yes, there is. Trapped by their ancient samurai ways, it takes a white Scientologist to set the samurai free.

A mighty battle is joined, the tiny samurai army vastly outnumbered by the machine-gun wielding Imperial Army. The Samurai put up a hell of a fight, but in the end, all are gunned down save Katsumoto, who, mortally wounded, gets to commit Sepukku after all. Only one man survives the slaughter, only one man isn’t ripped apart by hail of bullets tearing every one of his samurai comrades to shreds. That man is Algren.

It is Algren, then, who, post-battle, presents Katsumoto’s sword to the Emperor, who thus shames the Emperor and the rest of the Japanese for not having respected their own history. Justly humiliated, the Emperor stands up to his advisors. Thus is it the white man who saves Japanese tradition from those evil Japanese who would see it die.

And Algren? His work done, does he wander off into the Japanese wilderness with that lovely wife of the man he killed? You bet he does. A man reborn, living only for himself and his true love, à la Costner in Dances with Wolves. But not before having saved another culture from losing their heritage, quite unlike Costner, for whom respecting an oppressed peoples was enough, and only after having taken part in a great and noble martyrdom, without, à la Gibson, the inconvenience of actually dying.

The only thing left is for these gods among actors to join forces in a single movie and—I don’t know. Fight to the death? Save the noble earthlings from deadly space-alien-oppressors? Meld into one giant being and become one with the universe? I leave it to them to show me the way.

Maybe James Cameron can direct it.

The funny thing is, I always had associated these three actors in my mind, without any reasoning. But when I read the title of your article it all fell into place, before I even read the whole article, I knew what movie(s) these guys had in common. Nice article.

Glad you enjoyed it. Thanks for stopping by. If there are ever movies again, maybe we’ll luck out and these three will take my advice and team up.

The Stark reality is, (it’s appointed each man once to die then the judgment.)