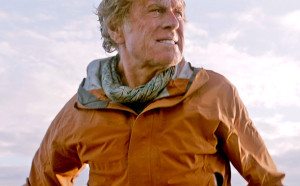

J.C. Chandor’s All Is Lost stars Robert Redford as ‘Our Man.’ That is the total and complete cast list. The character is not named as no one speaks to him for the entirety of the film. Not a soul. It is a solo voyage, without gimmick, and that’s exactly how it feels.

J.C. Chandor’s All Is Lost stars Robert Redford as ‘Our Man.’ That is the total and complete cast list. The character is not named as no one speaks to him for the entirety of the film. Not a soul. It is a solo voyage, without gimmick, and that’s exactly how it feels.

The feeling is like a coming up for air when you’re not sure if the anticipated breath will be your first or last.

If you want to see what Alfonso Cuaron’s Gravity should have been, just watch All Is Lost and imagine Our Man in space. Compare Redford’s subdued performance and the unfolding of his personal disaster to the more-impressive spectacle of orbital fiasco and the nattering of Sandra Bullock.

First, take a moment to name all the feature films you’ve seen that have only one actor. Wracking my brains — without asking the internet — I come up with one, and it’s a cheat: Spaulding Gray’s Monster in a Box, in which he performs one of his monologues. I’ve seen a mess of two-handers, including Gravity (which has a couple of extra voices but only two actors) and Boorman’s excellent pairing of Toshiro Mifune and Lee Marvin in Hell in the Pacific, but just one human on screen in a bona fide feature? Drawing a blank.

Even the internet has limited experience with true solo shows. Some suggest Moon, Duncan Jones’ enjoyable sci-fi drama, but that’s got Kevin Spacey as a computer voice and other personalities for lead Sam Rockwell to bounce off of. In fact, most one-man-films that people mention feature other voices, whether they’re on screen or not, and that means another actor. Some films have bookend segments with other characters, such as Cast Away or 127 Hours. Secret Honor, which is on my list to see, is like Monster in a Box; a staged monologue starring Phillip Baker Hall as Richard Nixon unraveling. Buried had Ryan Reynolds in a coffin and that’s a cool concept — but the film is mostly him talking on the phone.

Even Monster in a Box has Gray performing to an audience. Not so in All Is Lost. There is a moment when Our Man’s radio almost works, and crackly voices are heard speaking foreign tongues, but that’s it. No one here but us ghosts.

As a feature film, it is a stunning achievement and only partially due to Redford’s unsupported time on screen. The other mesmerizing aspect — and what truly sets All Is Lost off from a gorgeous but vacant film like Gravity — is the control of Redford’s performance.

When no one is around to see you, there is no use in wailing or thrashing about or even praying aloud. You see what has befallen you, you take stock, and you do what there is to be done or you die. This is how Our Man behaves and it is quietly shocking for its authenticity.

Bolstering Redford’s focused performance is J.C. Chandor’s equally ascetic script. Where in Gravity, everything that can go wrong does, and every occurrence is flayed for potential dramatic impact, in All Is Lost life is tense enough without exaggeration.

Bolstering Redford’s focused performance is J.C. Chandor’s equally ascetic script. Where in Gravity, everything that can go wrong does, and every occurrence is flayed for potential dramatic impact, in All Is Lost life is tense enough without exaggeration.

The film begins with delicately muted colors of sea and sky. Our Man is reading from a letter he has written — and this is the only voice over in the film and about 99% of the words you’ll hear spoken aloud. Then the camera floats past a hulking object that we eventually recognize as a container fallen adrift from a giant transport vessel. Nothing is amped; in fact the color, pace, and the performance all feel resigned.

All is lost.

From here, titles skip us back eight days and into the middle of the Indian Ocean. Our Man sails his 39′ yacht without companion. Asleep below, his boat collides with the rogue container, puncturing the hull just above the waterline. This is the start of his troubles.

It is our introduction to the aged sailor, looking every day of Redford’s 77 years. It is our first sign that we are going to see something normally kept hidden: one’s private reaction to setback. If you can, step outside yourself now to picture your behavior at a time of solitary crisis. Are you blasé like George Clooney’s Matt Kowalski in Gravity or are you on the verge of hallucinatory panic like Bullock’s Ryan Stone?

It is our introduction to the aged sailor, looking every day of Redford’s 77 years. It is our first sign that we are going to see something normally kept hidden: one’s private reaction to setback. If you can, step outside yourself now to picture your behavior at a time of solitary crisis. Are you blasé like George Clooney’s Matt Kowalski in Gravity or are you on the verge of hallucinatory panic like Bullock’s Ryan Stone?

Thousands of miles from anyone else, with your radio spoiled by seawater, who are you acting for? I suspect we either behave like Redford’s sailor or we’re fish food.

J.C. Chandor proved that he understood how people interact in his taut financial disaster film Margin Call; here he proves he can likewise be honest about how people behave on their own. He stays remote, allowing the gravity of the situation to carry its own weight without spectacle. As each added complication arrives in All Is Lost, they feel honestly unforced. If anything, you wonder how things could go so well for so long.

This allows you to create your own tension with which to flavor the picture. Being authentic, this tension cannot be escaped with a shake of the head. It cannot be soothed either, even though Alex Ebert (frontman of Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeroes) tries with a score that is as lullingly deceptive as the sea. Time and again I’d wrestle my clenched jaw open to realize the music, far from ratcheting up my angst, was doing what it could to keep me calm. Telling me to give in.

This allows you to create your own tension with which to flavor the picture. Being authentic, this tension cannot be escaped with a shake of the head. It cannot be soothed either, even though Alex Ebert (frontman of Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeroes) tries with a score that is as lullingly deceptive as the sea. Time and again I’d wrestle my clenched jaw open to realize the music, far from ratcheting up my angst, was doing what it could to keep me calm. Telling me to give in.

I’d be thinking, “and this is when the sharks come,” but they wouldn’t. Our Man makes no blunders of note. He simply perseveres, as there is no other living option.

The other thing to think about with any disaster film is how events such as these conclude. You can take Gravity as an example, or nearly any other of the genre. There are characters we care for. A crisis strikes, turning their world to turmoil. They struggle to survive and, almost always, manage to somehow, miraculously survive, perhaps with their child or sweetheart or dog (or dog-sweetheart if you’re watching a Harlan Ellison film).

This is not how most people experience true disaster. Most people see their world turn to turmoil and then die. We cannot all be Gene Hackman in The Poseidon Adventure. Most of us must go down with the ship or it isn’t a disaster in the first place.

This is not how most people experience true disaster. Most people see their world turn to turmoil and then die. We cannot all be Gene Hackman in The Poseidon Adventure. Most of us must go down with the ship or it isn’t a disaster in the first place.

There is some controversy about the ending of All Is Lost for this reason. Would Our Man survive an ordeal such as the one he faces in this work of fiction? I’m not saying he does: there is no spoiler here. I’m only posing the question for you.

As you watch All Is Lost, and you should, ask yourself if you’d survive. That is the film. Ask yourself if untrained astronaut Ryan Stone survives round after round of bullet-like pieces of satellite shrapnel to pilot various crafts with controls configured in unknown languages to finally find her feet beneath her.

She does not. This is what happens in films. This is what happens in films in which hope is predicated upon fantasy. That makes All Is Lost a powerful dose of anti-Gravity.

All Is Lost takes its lonely, alternative, authentic course. You may find the ending jarring, but take the time to consider what you’ve seen and what you see. I feel the conclusion marks a turn for the picture, but not in the direction one might originally assume.

There is one moment in the film that keeps coming back into my head. Robert Redford has finally written the letter that he begins the film reading aloud. He places it in a jar and twists the lid as tight as it can go. His arm swings back for a mighty throw, aiming to send his thoughts out to the world. But then he stops. What difference how far his strength will carry anything? He simply lets the jar fall into the water.

I’m sorry. I know that means little at this point, but I am. I tried. I think you would all agree that I tried. To be true, to be strong, to be kind, to love, to be right. But I wasn’t.

They should both have died and they both did not. As a metric of authenticity, ultimate survival does not seem to differentiate the two films. Survival in space is probably far less likely than survival in the ocean but if the setting is a stumbling block, there’s not a ton that a movie can convince us about space being surviveable. Everything will always seem like a long shot. Then again, we celebrate survivors precisely because they made it through situations with terrible odds, where we would expect survival to be unrealistic.

Similarly it strikes me that to dismiss panic as a valid response to a disaster is disingenuous, especially when the favored response is stoicism of the highest order. More importantly, in Gravity, that panic stops and is replaced by problem solving which leads to success. This character arc is not unlike Aron Ralston’s real life experience, going through periods of panicked desperation and problem solving. Again, I dispute the notion that a person who reacts with panic first and then calms down will be unable to survive an ordeal.

Perhaps talking to one’s self is less authentic than not talking to one’s self. I probably would agree with you on that one. But The Old Man and the Sea still remains one of my favorite books so I guess I’m someone who’s willing to overlook a lack of realism in fiction.

I would suggest that they both did die. If you consider the ending to All Is Lost, you might find that it is dreamy and illusory in a way that contrasts to the rest of the film, i.e. it isn’t actually happening. The hand that reaches for him is unreal.

I am not talking about panic being a false response. I’m talking about the way panic physically manifests without an audience. I’ve been genuinely panicked before when alone. Then, I felt like Ryan Stone but looked like Our Man. I think Our Man is terrified. He just has no one to show this to.

So he suffers quietly. But he suffers.

Aron Ralston is a good example to contrast to; how would he have acted without a camera to talk to? With no chance of anyone hearing his yells? Like Ryan Stone or like Our Man? You struggle against the problem, and then you do what you think best. Matt Kowalski was stoic. Our Man was something else; he was believable.

I just watched Gravity a couple days ago. All is Lost is not out here yet.

I agree with some of your criticisms, the scrips was a bit obvious and could have done with another couple of passes but I was still quite blown away by it in terms of the visuals and the overall story.

Indeed. Visually, it is thus-far unparalleled in terms of successful use of VFX. The overall story didn’t get in the way of that.

I saw All Is Lost tonight. Can’t say I liked it as much as you did. In contrast to Gravity, I liked the realism, and the lack of cheese, and the lack of Redford talking to himself or having a backstory. And the end, which I guess I can’t be spoilery about, since people have different opinions, but yeah, he’s dead. In Gravity she is certainly not dead, the whole point is that she survives. Sure it’d have been swell if she really did die in the capsule in that one scene, but no, it’s not that kind of movie.

So anyway, the thing is, that despite All Is Lost’s plusses, in the end I don’t feel like I’m left with anything more to ponder than I did with Gravity. It was a nice nail-biter of a survival movie, but I didn’t find anything deeper to engage with. Redford is an average man, not especially able nor smart, but neither unable nor dumb. He faces a bad situation, does the best he can, and it’s not enough. I didn’t even especially care about him one way or another.

As a metaphor for life, well, sure, I guess it’s fine. But what else is there to think about?

I liked it all right. But it’s not one that’s going to stick with me.

For me, it was a matter of re-evaluating the other, similar films I’d seen via this new perspective. And I expect I felt a bit like those who saw Z or Battle of Algiers when it opened did. Oh! Movies can also be this!

It wasn’t that there was no awareness of the camera, or sense that you were watching a movie, but there was a very tangible feeling, for me, that I was seeing a more honest depiction of disaster, and how that might look like for a solitary man who had no care for audience.

I also did not particularly feel for The Man in the film. He was just a man who got himself into a fix he couldn’t get out of. And nothing he did was for my benefit; no jabbering to himself, no dramatic outbursts, nothing. I also appreciate that he died, and it’s clear to me at least that he did. That is part of disaster and what we usually get is fantasy.

So what was fascinating to me was not the story, but that Chandor tried to tell an old story a new way. I think he succeeded. I don’t think I’ll watch traditional disaster films from now on without finding them stagey and cheesy (or more so than I already did).