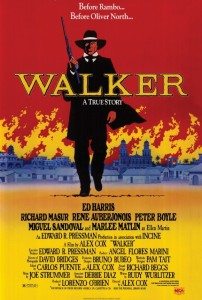

Walker, Alex Cox’s 1987 sort-of-but-not-really biopic about William Walker, an American who in the 1850s became President of Nicaragua, is a very weird movie. Coming from the director of Repo Man and Sid & Nancy, who would in later years make the wonderfully bizarro Revenger’s Tragedy, this is not surprising. What is surprising is that in ’87 Universal gave him $6 million to make it (Repo Man, with a $1.5 million budget, doubled its money, but Sid & Nancy lost money, and Straight To Hell was a straight bomb). Universal’s bet didn’t pay off. Walker was such a financial and critical disaster that Cox was essentially black-listed by every studio in Hollywood. He hasn’t been back since.

This is a crime. I blame the stupid bastards of the late ‘80s, whose hatred of this gem buried it before I ever knew it existed, and me a 16 year-old movie lover for whom Repo Man was a top ten film. Well. I have now seen Walker. Turns out it’s a uniquely excellent movie. A very unusual one, to be sure. The average movie-goer would, I suspect, watch this in a drooling stupor of confusion. But surely there were freaks going to movies in ’87! Why didn’t you speak up, weirdos?

To enjoy Walker, one must be open to a different form of historical fiction, one that leans heavily on the fiction side. The weird fiction side. Cox isn’t interested in literally re-creating what “really” happened (a fool’s errand taken on by many a fool); he’s interested in getting at the deeper truth of what this history teaches us, and how it is essentially interchangeable with the present.

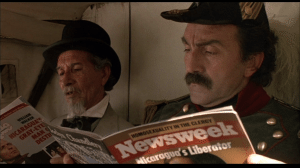

Cox turns time on its head in Walker through the not-at-all subtle use of anachronisms, which apparently really threw viewers at the time. Granted, it’s jarring. But this, I contend, is a good thing. More on those in a moment.

Historical dramas are expected to, above all, serious. Serious and important and, ideally, weighed down even further by a stately narrator, preferably Anthony Hopkins. Alex Cox threw all of that out the window. Walker is part serious drama, part cartoon, part satire, part Sam Peckinpah western. It’s narrated by a self-deluded madman. In a word, it’s kinda nuts. A so-called “acid western.” Who better to write it than Rudy Wurlitzer, screenwriter for Monte Hellman’s beloved cult car flick Two Lane Blacktop and Peckinpah’s Pat Garret & Billy The Kid? Not to mention the unproduced acid western script, Zebulon (which Peckinpah, Hal Ashby, and Jim Jarmusch had all at one time or another wanted to direct, and to which it is said Jarmusch’s eventual acid western, Dead Man, owes a thematic debt (and which script, to be more parenthetical still, Wurlitzer turned into a book, The Drop Edge of Yonder, in ’08; I’ll be reading that one soon)).

The story follows William Walker (Ed Harris), soldier of fortune, believer in Manifest Destiny, who’s introduced in the midst of a violent gunfight in Mexico, filmed with excessive blood and bullets ala Peckinpah, scored by Joe Strummer of The Clash, whose music throughout is really rather goofy, lending a confusing air to matters from the start. Walker is prosecuted by the U.S. Government for starting an insurrection in Mexico, but weasels his way free, speechifying all the way about Americans’ God-given right to dominate the western hemisphere by freeing its neighbors from oppression. He narrates the film reading passages from his journal, in which he portrays himself the savior of all mankind, more or less, as God’s very hand at work upon the earth.

Post-trial, Walker’s all set to be married (Marlee Matlin plays his wife) and settle down to run a newspaper, but millionaire Cornelius Vanderbilt (Peter Boyle, at least as over the top as his version of Dr. Frankenstein the younger’s monster) hires Walker to take an army of brigands down to Nicaragua to overthrow its government, thereby freeing up Vanderbilt’s overland shipping route. Walker likes the idea, but his wife is outraged. Anyway, she dies, and off he goes.

Anachronisms start popping up later in the film, though I’m sure I missed earlier, more subtle ones. Eventually, once Walker has murderously rid Nicaragua of its government and appointed himself El Presidente, lackeys are seen reading Time and Newsweek with cover photos of Walker, people use lighters, drink bottles of Coke, and in one scene, in a horse-drawn carriage, where Walker’s Nicaraguan mistress, the wife of the former President, tells him she wants Americans out of the country, Cox cuts to a modern car driving past the horses. At the end of the movie a giant army helicopter lands and the Marines come pouring out. It’s all a bit bonkers.

Not at all bonkers is the genesis of the movie. The U.S. was waging an illegal war in Nicaragua in the mid ‘80s, and Cox visited to find out for himself what was going on. Were the people of the country terrified by their Sandinista leaders? Did they yearn for the CIA backed Contras to take over? According to Cox, no. The people were terrified by the tens of thousands of American troops on their borders. The anachronisms of the movie not only link past with present, they erase the space between them. What is happening in the movie is happening now; it’s always been happening; it’s one long war of occupation. That this message is in part delivered as a gag, as a cartoon, as a riff on Sergio Leone spaghetti westerns, is the sort of thing liable to turn off audiences, and critics too.

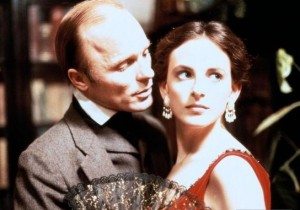

But how could anyone not be riveted by Ed Harris as Walker? This might be the best performance of his career. It’s not easy carrying a movie when your character is fundamendally corrupt, hypocritical, murderous, unrepentant–in a word, evil. He plays Walker with focused steeliness. He’s calm, strong, hard. He never smiles. He rarely raises his voice. No matter the madcap antics of those around him, he remains utterly unfazed. Like Colonel Kilgore he walks through battles head held high, and not a bullet touches him. Above all, he believes in himself and his mission on earth, given him as an American by God above. If he has to kill Nicaraguans to save them, he’ll do it. His actions are by definition in the right, from beginning to his ignominious end. He’s akin to Klaus Kinski’s “white man in foreign lands” characters in Herzog’s Aguirre, The Wrath of God, Fitzcarraldo, and Cobra Verde.

Walker sees himself as a Puritan. It’s not he who seduces the President’s wife, it’s she who insists Walker take her. “I have a weakness for small men,” she says, “Small Puritans obsessed by power.” The metaphor is hardly subtle. Decent, strong America, pulled against its will into the seductive bosom of poor, helpless Nicaragua. But once she recognizes the monster she’s invited into her bedroom, once she’s demanded it leave, only then does she come to realize there’s no getting rid of it. The monster is here to stay.

Walker‘s end credits play over a small television screen showing clips of ‘80s Nicaraguan war footage, Reagan speeches, soldiers talking about what the Americans are doing for the poor people of this impoverished country. Certainly another reason for the movie’s failure was its unapologetic criticism of the U.S. Cox pulls no punches in here. He lays it out as he sees it, and it’s a damning vision. With jokes.

I will have to watch this.

And it streaming! Nice.

That is no ordinary asshole.

this sounds great

The “Illegal war” in Nicaragua was waged by the Sandinistas, thousands of civilians killed, including 15,000 Miskito tribal members. Cox was a liar.