I’ve been thinking about backstory, thanks to the Evil One’s Spiderman post, in which he points out what should be to all sentient beings blindingly obvious, that no one on planet Earth needs to see another movie about how Spiderman became Spiderman. He was bitten by a radioactive spider. Case closed. How much more beating can this dead horse take? According to Columbia Pictures, another two hours and sixteen minutes worth. Why? What is it about bringing backstory into the foreground of movies that’s so attractive to filmmakers? Two reasons. One, it satiates what I will argue is an imaginary audience need, and two, it’s easy.

Look at Batman Begins. It’s literally two hours and ten minutes of backstory. It ends with Batman having become Batman. Finally! Mysteriously, this is seen as necessary, as though an audience not shown a character’s entire life history won’t care about them. This is not to say that Batman Begins is bad. Not entirely, anyway. Nolan is talented and smart, if utterly lacking in subtlety and emotion. He fills the movie with compelling visuals and gives it a suitably dark and scary vibe. But my first thought when it ended was, “Whew! Got that over with. Now we can get to an actual Batman movie.”

Which that’s what the sequel is. Only it shouldn’t have been. A sequel, I mean. It should have come first.

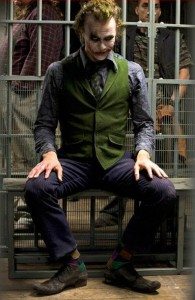

Here’s an experiment. Imagine you’ve never seen Batman Begins. Imagine you’ve never seen any Batman movie. Imagine further that you’re only vaguely aware of this superhero named Batman who dresses like a bat and fights crime. Now imagine watching The Dark Knight. Would you be confused? Would nothing make sense? Would you spend the whole movie thinking, “But what about his childhood? What were his parents like? Why bats? Why not Frogman? Frogs are cool. Criminals could lick him and suffer debilitating hallucinogenic visions! How come he’s so good at fighting? Who did he train with? How did he learn to conquer the fear that gnaws like so many hellish demons at the hearts of all humankind?” No, you would not. You would instead watch a movie about interesting characters doing things. That’s what movies are, that’s all they need to be, that’s all any drama needs to be: characters doing things.

I mean Christ, they say it right there in Batman Begins! In what must be the most emotionally blank moment in the movie, Rachel, seeing Bruce, her childhood love, for the first time since his return from presumed death, instead of showing even a hint of emotion, decides to lay some heady thematic juju on him and says, “It’s not who you are underneath, it’s what you do that defines you.” Exactly! Thank you. Forget about Batman, this line explains precisely what it is that makes characters interesting. It’s what they do.

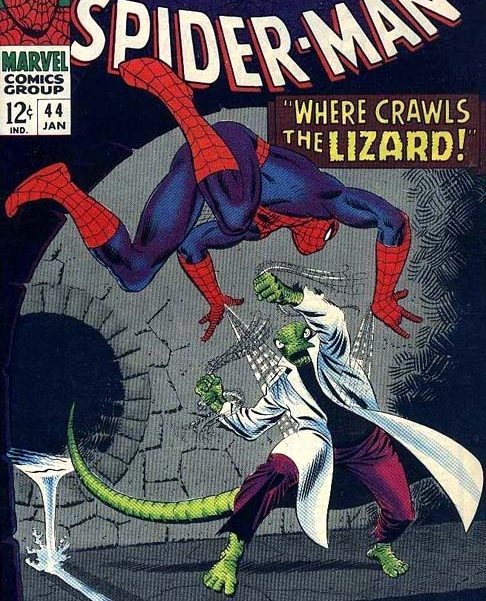

I know, origin stories are the bread and butter of comic books. We all want to know how the superhero came to be the superhero. Only do we really? I think we think we want to know, because being humans we’re incurably curious, but to what end? Try another experiment. Imagine you’re actually living in the world where suddenly Spiderman appears. You and a friend see him swinging around fighting a giant lizard on a building.

You: Holy shit! What the FUCK?! Do you fucking SEE that?! Jesus fucking Christ! What the fuck is that!?

Friend: Who, the guy in tights? That’s Spiderman. Dude was all over the news last night.

You: Spiderman? But I mean—fuck! He’s all like sticking to that building! He’s shooting webs from his fucking hands, man! He’s super-duper strong! He’s whipping that giant lizard man’s ASS! Oh my god! Everything we thought we knew about reality is WRONG! Up is down! Left is right! Dogs and cats, living together! How is it possible? Why? WHY?!

Friend: Chill, man. He used to be like this regular nerdy kid. Only then a radioactive spider bit him.

You: Radioactive spider bite, you say? Well, that explains things. Cool. Let’s get some lunch.

So there we have it: the explanation explains everything by explaining nothing. And it’s designed to do just that. That’s the thing. It’s that simple. It’s not supposed to be some vast, complicated, hours long exegesis. He’s a superhero. In a comic. He has powers. How’d he get them? Radioactive spider. Gamma rays. Cosmic rays. Born to a fish lady in Atlantis. Talks to the ants. Bitter about dead parents. Bitter about adamantium skeleton. Simple explanations are all we need.

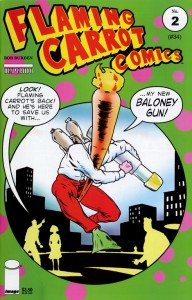

But what about a comic book superhero fewer people know about? Like Iron Man? Or one almost no one knows about, like The Flaming Carrot? (Which by the way, where the fuck is my Flaming Carrot movie?) If a movie is made about them, certainly we need to hear their backstories. Don’t we?

No! Stop saying that! Pay attention. If we’re shown a guy in a crazy metal suit that fucking flies, and he’s zipping around the world kicking bad-guy ass, then we’re going to be interested in what that guy does next regardless of how he came to find such a swell metal costume. And if a weird dude with flippers on his feet and a burning carrot for a head tools around in fast cars with fast women fighting even weirder dudes for the good of humankind, we don’t need to know about the time his drunken father beat him with a giant carrot. If in fact that’s The Flaming Carrot’s origin. Which I’m sure it isn’t. But who cares?

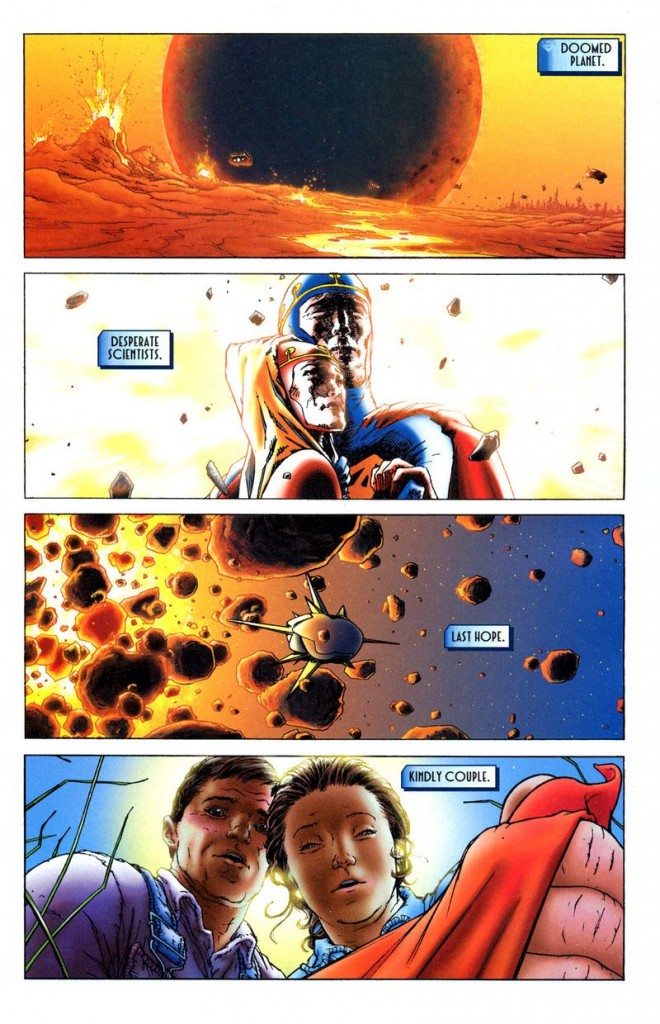

I don’t read comics much, I’m too busy watching movies, but I saw this recent Superman comic called All Star Superman, and the first three pages constitute the single best telling of a super-hero origin story I’ve ever seen, anywhere, in any form. Here it is:

How brilliant is that? Doomed planet. Desperate scientists. Last Hope. Kindly Couple. FUCKING SUPERMAN. And now, on with the story!

Knowing the full story of how a character came to be who they are is not a movie. It’s information we don’t need. We think we do. Filmmakers assume it must be so. But it simply isn’t the case.

The other reason Hollywood loves telling superhero origin stories is that it’s easy. Not easy to make them good, because they suck, all of them. Easy to do. It’s how writers naturally build characters. They think up backstories for their characters, where they grew up, who their parents were, how they got laid by that cheerleader in the girl’s bathroom after the big game. Just take a look at my Supreme Being bio: that shit is fun and easy to write. And because they (writers) have written what to them are many pages of fascinating and meaningful incidents, they start believing an audience needs to see it played out to, you know, get the character. It’s because everyone in Hollywood has spent their entire lives in therapy, trying desperately to understand themselves through the secrets of their childhoods, hoping they’ll unearth in the deep snows of the past a sled named Rosebud. They think this is how you come to know people, by studying who they were in minute, crushing detail. Unfortunately, nothing could be less true for a movie. In a movie, all we need to see is someone doing something, and we’re hooked.

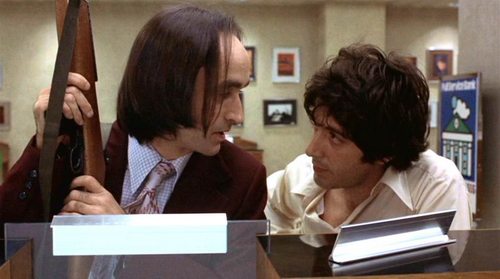

Here’s a movie that shows both how simply watching characters act compels us to keep watching, and how backstory may be woven into the fabric of the story. If a superhero movie used this as a model, it would be called an act of genius. The movie: Dog Day Afternoon. Haven’t seen it? I’ll wait.

Fucking amazing, right? I know. How come no one makes movies like that anymore?

We start with a bank and three guys in a car outside it. They rush in waving guns, they’re robbing it, and they don’t look too professional. In fact the youngest guy says he can’t do it and leaves. He has to be talked out of taking the car because hey, we’re robbing a bank here, we need the getaway car.

We’re left with Sonny and Sal in the bank. They’ve never done this before. Sonny is doing his damnedest to make things go smoothly. But the robbery in progress is spotted, the cops surround the place, it’s a stand-off. Now, do we need to hear about Sonny’s childhood? Or Sal’s? No. We’re fascinated by what they’re doing. They’re stuck in the bank. They’ve got hostages. They’re surrounded. What will they do? How will they get out? That’s all we want to know. That’s all we need to know.

Then, deep into the movie, Sonny tells the cops he wants to talk to his wife. They find her, an obese women with a bunch of screaming kids, only that’s not the wife he meant. He meant his other wife, Leon, brought in from the psych ward at Bellevue, whose desired sex-change operation Sonny intended to pay for with the spoils of the robbery.

Now that’s backstory gold! We’ve lived with this character for so long we forgot we even wanted to know why he was robbing the bank. And we learn it in a way demanded of by character. Sonny is arranging to get a plane to fly him out of the country and he wants to take Leon with him. In other words, we have to learn about this facet of who he is for the story to unfold. Their scene talking on the phone is simply one of the best ever filmed. It works because we already know Sonny. We know him through what he’s done and how he’s gone about doing it.

Would this have worked at the start of the film? What if we’d had to endure twenty-five minutes of Sonny’s life at home, his secret life with Leon, Sal’s background, etc. and so on, until finally, once we fully understood who they were and why they were robbing the bank, they actually went about robbing the bank? We would have said: start the fucking movie already!

In superhero movies it’s not twenty-five minutes. It’s an hour, an hour and a half, or lately the whole damn movie. But we’ve conned ourselved into thinking that for these kinds of movies it’s necessary. It isn’t.

Peter Parker swings around fighting crime. An evil supervillain is at large. Peter loves a girl. Two thirds of the way through, he reveals who he is to the girl, and tells her, maybe with a few minutes of flashback, how he came to be who he is. That’s all the backstory any superhero movie needs. It’s backstory motivated by the story and by the character.

Look at Alien. A ship flies quietly through space when suddenly its computer systems come to life, its lights turn on, its sleeping passengers are awoken, all because of a beacon sounding on a nearby planet. No backstory, no lead-in, it just starts. And do we ever learn a single thing about Sigourney Weaver’s character Ripley? Nope. Not a word. We simply watch her act. All we learn about everyone on that ship comes from watching how they behave.

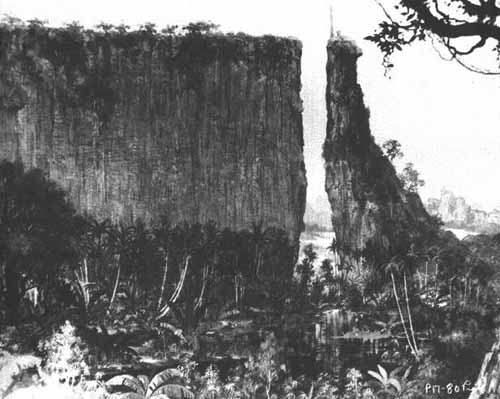

A last example of misused backstory, a movie much loved, but so it goes: Pixar’s Up. Me, I didn’t like it so much. Yes, it looked great—I love a visual nod to The Lost World as much as the next stop-motion fanatic—but the story and characters never cohered into anything meaningful for me. People who love the movie have told me that the opening segment, a ten minute (maybe less? It felt like ten) sequence showing the life history of our hero, Carl, is their favorite part. And this is Pixar, they know how to tell a story (usually), so it’s a very sweet and funny sequence. The thing is, it’s all backstory. It’s a mini-movie to watch before the actual movie starts.

Why not begin at the beginning, with old Carl about to have his house demolished only to launch it on a mad trip into the sky with a thousand balloons? Is this not interesting? Of course it is! It’s weird and different and totally compelling. This strange kid ends up with him, they zip away into the clouds, this is great stuff. We in the audience would be marveling at it and asking the best of all questions: why are they doing this? What’s going to happen next?

As for the lovely opening sequence, there’s no need to lose it. It would work perfectly as a reveal later in the movie, at the point when the mystery of what Carl is up to has been stretched as far as possible, when a character in the movie (and by extension we in the audience) finally needs to know what’s driving him.

I think Pixar put this piece at the outset out of fear. Fear that their story was a little too unusual for audiences. Why is that old man flying his house away? they feared people would ask. Even at lauded studios like Pixar, the rule of thumb is: explain everything at every moment in totality to insure that no one in the audience for so much as a single second questions what they’re watching.

We have been fooled into thinking origin stories are needed in superhero movies, so much so that we even have a special name for them: yeah, just that, origin stories. All they are is backstory, character bios, with a pretty new name. We don’t need these stories repeated in movie after movie, reboot after reboot. We don’t even need them the first time. We only need characters who act. That’s enough.

it is, really, all part of the stupid problem.

that is: hollywood insists on believing that audiences are too stupid to understand anything that has not been stapled to their heads. this has not always been the case (Dog Day Afternoon). but lately it’s gotten so out of control, they’re taking properties that IN NO WAY need a movie version (Battleship, Monopoly, etc) and actually making them into movies—why? because using concepts in the public consciousness gives them a jump start on all the explaining their movies will bore us to death with.

I would be interested to hear some discussion of origin stories done well—because while I agree for the most part, I also think there’s nothing inherently wrong with an origin story. It just needs to be the story that’s worth telling. I’m thinking of Robocop, for example, in which the story is about society’s loss of humanity and so showing Murphy’s allegorical loss helps us to consider the theme.

True, there are no rules. Robocop is a good counter-example, for exactly the reasons you cite. So it can be done. With Robocop I guess it feels like they’re telling a story about this crazy thing that happened to this guy. Which is how one could define almost any movie. Most movies involve a character going through a change, ending up, in however large or small a way, a different person than when the movie started. In that sense, every movie tells a kind of origin story, and a superhero version is simply writ large and obvious.

Yet with Batman and Superman and Spiderman and so on, somehow it always feels like we’re being brought up to speed with someone, and only once there may the real story start. A failure of emphasis? Of theme? Something like that…

I think for some reason it’s related to the idea that people need to know exactly how an unfamiliar universe works, without having to use their imaginations or intelligence. They can’t take for granted the idea of a shared humanity with a character, but need to be handheld and shown how they can relate.

I’ve read a lot of fantasy, crappy and non-crappy (yeah, I know the idea of non-crappy fantasy is arguable), from the early days of fantasy (Tolkien, Lieber, Moorecock etc) to today, and the biggest change is the idea that readers now seem to need to know exactly how the world works. What does each magic word do? Quantifiably how powerful is each character? Who is the best fighter? WHY is that character more powerful than the other (his medichlorian count is amazing!)? Some of the better writers don’t adhere to this, but most do. Here origin stories are king.

In contrast sci-fi, from the days of Niven, Asimov, to some extent Heinlein, modern sci-fi is less heavy on the explanations as to how

things work.

So we end up with stories requiring less effort to understand, and less effort to write.

At one point I agree with you. Like, I can’t believe we’re getting ANOTHER fucking Superman movie that’s gonna explain his origin again. Is there ANYTHING else we can learn from this?

But I can’t help but disagree with you about your main point. A good origin story that change our perceptions of that character, making us view all the stories we’ve already read in different lights. To start with a loaded example, take Batman: The Killing Joke, which gave us the possibility that the Joker was never actually a criminal mastermind, but was just a poor lonely schlub. If you choose to believe that origin (or even if you consider that it’s even one of several possible origins he might have), it casts a whole new aspect–one that is simultaneously tragic and chilling–on everything the Joker was, is, and does.

For fans like me who really love thinking about what makes these characters tick, specifics ARE important. Consider what it actually means to have a Batman who captured Joe Chill versus a Batman who never did. Either version means something very different for why Batman does what he does, whether it’s out of his personal vendetta against crime or because he’s a good person who wants to see justice done. Both are Batman, but they’re different KINDS of Batmen. The specifics have far-reaching implications for the personalities and motives of these characters. In Batman’s case, it could mean the difference between a Batman who’s an inspiring hero and a Batman who’s a vengeful dick.

It’s not just limited to comics, either. Take John Gardner’s wonderful novel, Grendel, a literary prequel which has forever changed how I’ll view the monsters from Beowulf. A good backstory, skillfully told, can add a whole new dimension even to characters who are CENTURIES old, partially because a new telling can better reflect a contemporary viewpoint. So the idea that characters who are “decades old” are somehow LESS in need of new/revised origins is just bizarre to me. As these characters have evolved over the years, so too do their origins need to reflect that development. Look how Iron Man was reinvented for modern times in 2008’s film(also note that the origin portion of his story has been far and away the most enjoyable part of the Iron Man series to date).

You use your example for Up, which work later as a reveal. And I mean, yeah I suppose so, but WHY!? What kind of conflict does that kind of late reveal create? What kind of conflict does it prevent? Why do that when you can set it up from the beginning? The opening sequence from Up is the cutuest, most heartbreaking stuff to come out of Pixar, and from that moment on, for the rest of the entire movie, I WANT TO SEE CARL WIN. I want to see him succeed. Ten minutes into the film I completely understand his character, his motivations, and now I’m emotionally-invested in the story.

The opposite of this being the recent John Carter movie, where we are suppose to connect with John as our audience stand-in. He’s the guy from Earth who comes to this strange land of Mars and learns about it as we learn about it…but we spend half the movie NOT KNOWING WHAT HE’S THINKING OR WHY HE’S THINKING IT. Halfway through the movie, we get the character reveal that his family was murdered and that’s why he’s kinda a reclusive dickhead. Which is just…bizarre. There’s no purpose to that. We spend half the film looking on the outside at this character we’re suppose to connect with.

Origins(and how you tell them) matter because they’re all about characters, and characters is really all a story is about. Anything that can flesh those characters out, make them deeper, make them even more interesting and explores their motivations and how they develop, that is what makes their actions MATTER.

Origins and backstory aren’t the only ways to accomplish this, but they are an extremely effective one when used well.

Well…I hope that wasn’t too long! I just see this adverse reaction to origin stories a lot and I just needed to write this all down.

This may indeed all come down to what everything comes down to, which is HOW one goes about telling these stories. You’re right, we often do want to know what makes these people tick. But I think that more often than not, we don’t need an entire two hour movie to give us the info we need. And as I argue, I find that the beginning of a movie is almost always the worst place to put it.

With Up, do you really need to have ten minutes of backstory to care about Carl? Sure it worked; it told you a sad and beautiful story. That’s why they put it there. So why not open every movie with a scene where the main character saves a dog from being run over? We’d care about them then for sure!

The reason you use the opening later is simply because stories work better when you start at the beginning. I contend that you would care plenty about Carl without having that intro. You see this guy holding out against big business to save his house? You’d care. And then he flies it away with balloons? I don’t accept that you need all of his motivations carefully laid out in advance for you. You won’t get bored that quickly. And as a storyteller, giving yourself that backstory to parcel out at a later time, when it matters, gives you a huge amount of power. It becomes a more effective, powerful tool when used thoughtfully and purposefully.

Sure, you COULD put the Up opening later, and the all that saying no to the man kind of stuff would be “good enough”. But by using it from the beginning, it colors every single action Carl makes in a new, interesting light. He doesn’t just want his house because it’s his house gosh-darn it, that house has a special place in his heart because it’s the only part of his deceased wife he has left. He met her there, they grew up there, and he will not let it go, not for anything. When he flies away in the balloons, sure that’s crazy ans visually interesting and I wonder what that’s about. But with the opening in mind, his motivations are understandable, because of the promise he made to Ellie. He’s a more interesting, complex, and fully-rounded character with that backstory; why in the heck would you withold that? Again, with the John Carter example, what purpose does that serve keeping that information close to your chest? What conflict does that create, or more importantly, what does conflict that it prevent?

Those simple explanations or lack of backstory are “good enough”(Batman the Animated Series just starts off with Batman doing his thing from episode 1, and it’s better for it), and if that’s your personal preference. But as someone who spends a lot of time thinking about the characters, strong backstories and great origins(like Batman and Spider-Man have) that can fill out details and make them more complex or interesting, I’ll take that, too.

The point I’m making is that all of that information about Carl’s history is MORE effective if it is revealed later, and if that reveal is motivated by the telling of the story.

Everything you’re saying in terms of his past coloring his present IS STILL THERE. It colors everything you’ve already watched in an entirely new light. It makes everything glow in retrospect.

It is in fact MORE INTERESTING to NOT know about a character’s past at first. Because by being forced to ask ourselves WHAT is motivating a character and WHY they’re doing what they’re doing, the answer, when given, is far more satisfying. In fact, it IS satisfying, which is enough. When I’m told all of Carl’s history at the outset, it is satisfying nothing, because I’ve yet to ask any questions. It’s merely information being dumped on me. If it’s told well, that’s nice. If it then colors what comes next, that’s fine. But it satisfies no need.

Revealed later in the story, that info now answers MY questions and that feels GOOD. Not only that, it imbues all that came before with new meaning and power. Suddenly the act of rewatching the film becomes exciting, because all of those scenes you saw in one light on the first viewing you now see in a whole new way.

Being spoon-fed backstory at the start of a movie is the equivalent of being given a hand-out when you enter the theater detailing the life histories of all the characters you’re about to see. Which would be ridiculous. What you need to know about the characters, however simple or complex that info may turn out to be, should be revealed in the telling of the story.

Of course alll of what I’m saying assumes we’re talking about a good movie. Nothing works in John Carter. (which I admit to knowing only through mr. Evil One, who unlike me was brave enough to sit through it).

This conversation, which I am enjoying reading and considering, makes me think about what I was saying last week in re: Spoilers in my Grey Ghost post. We are basically attacking the same issue from different directions.

What SB is saying here about origin stories is that they are, essentially, acting as their own spoilers. And spoiled films can still be good—some excellent—but why spoil a film? Up is a good example because it is a great film. The opening with Carl and Ellie is fantastic, but you have to ask yourself two questions: 1) what if that was the whole movie? doesn’t it work on it’s own and, if so, why place it there? and 2) how would you feel if that powerful sadness and loss was revealed in contrast to another plot point, say the kid’s discussion of his absent father?

Do we need to start Up sad? How does that effect our emotional journey in the film? It makes us feel like Carl, which isn’t bad, but what if instead we felt like Russel? Full of hope instead of devoid of hope?

I also want to say that criticizing a film is different from not liking a film. I’m planning on saying a whole bunch of bad things about The Dark Knight in my next post, but really: I enjoy that film every time I watch it.

Pingback: Prognosticontemplation | Stand By For Mind Control·