The most alarming thing a filmmaker can say when turning a novel into a movie is, “We’re being true to the book.” This is a terrible thing to do. What does the book care about how true you are to it? The book is the book. It’s not going anywhere. There it is on your shelf. What filmmakers should be worrying about is being true to their movie. Worse still, filmmakers only mean the phrase in relation to the book’s plot, because what else can they directly lift? The internal musings and motivations of the characters? The pretty sentences? If they like the pretty sentences, they inevitably stick them into movie in the form of voice-over, which few filmmakers have any idea how to use. Their movies end up feeling like kindergarten story-time: teacher shows you the pictures, then reads the page describing what you’re looking at.

Great books are great because of how they’re written, not because of their plots. People like Stephen King, Michael Crichton, and John Grisham are great for adapting, because they’re all about plot. Whereas someone like Kurt Vonnegut is all about tone. To translate his work into film would require finding a cinematic way to mimic the tone he creates with words. This is not easy. By reducing a book to its plot and imagining you’re being “true” to it is to strip it of everything that makes it work on the page. “The book was better,” you inevitably end up saying.

Stanley Kubrick is a rare example of a filmmaker who understood how to adapt a book into a movie. He did it by being true to his movie and ignoring anything in the book that didn’t fit. Did you know there was no hedge maze in King’s novel The Shining? One among many changes. Dr. Strangelove is based on Red Alert, a very serious book about the possibility of nuclear annihilation. Weeks into adapting it into a screenplay, Kubrick came to realize that it was simply too outrageous not to laugh at. So he turned it into a comedy. With a pie fight (which yes, he edited out. But he shot it. For like five days). When Kubrick uses voice-over narration, it’s sparse and meaningful. It sets the scenes or comments on them in ways that bring you into the movie instead of taking you out.

The best book to film adaptations are always those that take a thread from the book and focus on it, that have a very clear idea of what they’re saying, and stick to it. If you worry yourself about angering fans, you’re going to leave in parts you should have left out, and replace parts you should have built the whole thing around to begin with. You end up with a Frankenstein’s monster of a creation, something that shambles around in imitation of the book without having its brain or its heart, moaning and drooling and drowning little girls in lakes. What can you do but chase it out of town with pitchforks and set it on fire?

The best adaptions of books are so true to themselves that they leave the door open for future adaptations completely different in nature. Let’s take a look at two books ripe for new interpretations.

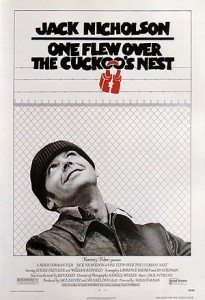

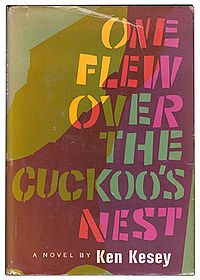

One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest by Ken Kesey

It’s a safe bet you’ve seen the ’75 movie version directed by Milos Forman. Jack Nicholson is Randall Patrick McMurphy, a troublemaker who gets himself out of being sent to a prison work farm (on an accusation of statutory rape) by feigning insanity. He figures a few months in the funny farm will be a breeze. He doesn’t figure on Nurse Ratched, the subtly manipulative ruler of the insane. All McMurphy has to do is keep quiet and play by the rules, to shut up and take it. But he’s simply not made to stand still in the face of oppression. He can’t help but push Ratched’s buttons and implore the men to stand up for themselves.

Chief Bromden is a seemingly deaf and dumb Indian McMurphy befriends. It’s Bromden who in the end takes McMurphy’s defiance to heart and escapes.

There’s nothing wrong with the movie. It does exactly what an adaptation should do: take a central theme, in this case the defiance of institutional authority, and focus on it exclusively. Nicholson is great, Louise Fletcher as Ratched is great, it’s got Danny Devito and Christopher Lloyd and Scatman Crothers and Brad Dourif. It’s a wonderful movie. And it differs from the book in major ways.

Kesey’s novel is narrated by Bromden. It’s his story, in which McMurphy plays a central role. The McMurphy in the book isn’t as fun-loving and heroic as in the movie. He’s a troubled man. For all his rebellion he can’t escape from himself, and there are moments, like during the ride back from the boat trip, where the sadness resulting from this shines through.

Bromden, meanwhile, is haunted by bizarre dreams and visions of a mechanistic world lying just beneath the surface of reality, of a huge underground machine controlling the entire world. He calls this machine the Combine. Ratched and the orderlies are mere tools of this larger oppressive force. He sees a green fog rising up and consuming him. The Combine is not only working in the mental institution. It’s everywhere. It’s American society, of which the workings of the institution are but a microcosm. Bromden recalls his learning about it in his childhood when he watched his once powerful father beaten down by the government. Bromden never recovered.

Kesey wrote the book after working in a mental institution and after and during the time he spent as a test subject for an interesting new substance called LSD. The book is, as you might imagine, full of dark, surreal imagery.

If I was making a new movie of Cuckoo’s Nest, it would first and foremost include the visually surreal aspects of it. Bromden’s visions would be central. He would be the main character. The movie would be about his struggle to break free of the Combine. The institution and those in it would appear as seen through his eyes, however distorted the vision. And as Bromden learns through McMurphy to find the strength he once possessed, his vision would become clearer, and what once appeared imposing and demonic would become normal and, ultimately, easily conquered.

The movie would necessarily share many key scenes with Forman’s version. Seen through Bromden’s eyes, these scenes would be the same yet very different. The movies would inevitably be compared, but by using the book as the basis for something new, and in the process changing and altering the book to fit the concept of the new movie, you’d end up with something unique.

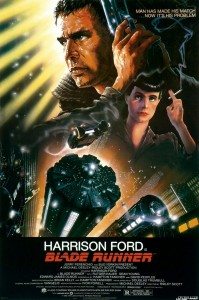

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K. Dick

The movie based on this book, Blade Runner, directed by Ridley Scott, could not be improved upon. Visually, after 2001 and Metropolis, it’s the most influential science fiction movie ever made. And it’s nothing at all like the book.

First of all, the terms “blade runner” and “replicant” aren’t even in the book. The movie focuses entirely on Rick Deckard hunting down replicants who’ve illegally returned to Earth from an off-world colony and killing them. Thematically, the movie is about what it means to be human. It uses the replicants asking their creator, Tyrell, for more life, and his refusal, telling them they’re programmed for only so many years, after which they will die, as a metaphor for the very human desire not to die, to meet their maker and beg for more time. The movie equates the replicants with humans, asking if there’s really any difference. At the end of the movie, as Deckard escapes with Rachel, it’s revealed that Deckard too is a replicant (not so in the originally released version, but made explicit by Scott in all subsequent cuts of the movie).

Deckard is not a replicant in the book. He is very human. Thematically, the book has a lot going on. It’s one of PKD’s weirder books (and that’s saying a lot for a man known for creating characters like the telepathic slime mold Lord Running Clam). The book doesn’t equate humans with androids. It asks the question whether or not androids could ever feel what humans feel, could need what humans need. The book is about empathy. Empathy is referenced in the movie; it’s the basis for the Voigt-Kampff test. But it’s not the focus the way it is in the book.

If I was making a new movie of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? I’d focus on the theme of empathy and Deckard’s struggle with it, using his desire for a real pet as the thread that runs through the story. In the world of the book, real animals are rare. To have a real animal is to have high social status. The story starts after Deckard’s real sheep has died. He’s replaced it with a synthetic one, but believes that only by being able to afford a real animal will his life have meaning. He agrees to hunt down the escaped Nexus-6 androids to earn the money to buy one.

Deckard begins to fall apart when he questions his own ability to empathize. In killing the androids he’s faced with questions of morality and humanity, and has to figure out for himself why it is that humans differ from machines. In the end he catches and kills the last androids when they give themselves away by failing to show empathy for a lone spider.

Deckard and his depressed wife (he’s married in the book) and everyone else still on Earth use something called a mood organ to program moods for themselves. Their religion, called Mercerism, involves an Empathy Box though which they’re able to join a collective consciousness and experience the suffering of Wilbur Mercer, the Messiah. A second religion takes the form of a TV show called Buster Friendly and His Friendly Friends. Buster is an android, it turns out. It’s a religion for androids. Why would androids need religion, PKD wonders?

One of the strangest, most paranoid sequences in the book has Deckard brought to what he’s told is the real police station in San Francisco (in which city the book is set). The station he’s been working at is a fake, he’s told. And he, Deckard, is really an android. He’s not sure what to believe. Finally he learns that the whole station is staffed by androids. It’s a shadow-police station known only to them.

In the end, once Deckard kills the androids, there’s a surreal scene in an Oregon desert where Deckard finds a real toad, the favorite animal of Mercer. He brings it home, where is wife discovers the toad is synthetic. Deckard decides he prefers to know that it’s a fake.

With all of that you could make three new movies out of this book, providing you do what Hampton Fancher and David Webb Peoples (the writers of Blade Runner) did: stay true to your movie. It would be less a film noir and more about one man’s struggle with his own humanity. More so than Cuckoo’s Nest, it would hardly resemble the original movie at all.

Of course this whole theory requires that these proposed remakes are made by artists as inspired as those who made the first versions. One look at Stephen King’s TV miniseries version of The Shining makes clear the risks in revisiting the basis of an iconic movie. But it could be done. And in the case of these two books, I’d love to see the results.

Love it. I’ve always wanted to see a Cuckoo’s Nest film from Chief’s point of view.

Considering the CGI we have at our fingertips these days, you could really create a strikingly surreal movie that included all of his visions. Plus having a man who doesn’t speak for most of the movie as your lead would be intriguing.

I have just learned that Kesey was originally writing his own script for Cuckoo’s Nest for Hal Ashby to direct. The producers balked at the casting of Nicholson and it fell apart… so Milos Foreman ended up making the existing version, with Nicholson of course.

Now, if only I can track down what exists of the Kesey script! I bet Ashby’s version would have been INSANE.

Any Academy Members out there who want to hook me up?

http://collections.oscars.org/link/papers/200