“I still watch sport because it has remained something in which the human body doesn’t lie. Politics, cinema, and literature can lie, not sport.” – Jean-Luc Godard, 2001

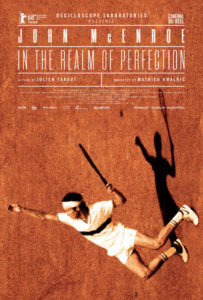

It was this quote director Julien Faraut had in mind when he made his mesmerizing new documentary, John McEnroe: In the Realm of Perfection, a documentary that both is and is not about John McEnroe.

Faraut’s documentary is poetic, abstract, and philosophical. It is exactly what the currently paint-by-numbers world of documentary film needs. It’s an original.

It is in no way at all about the life and career of John McEnroe. It is about an idea, the idea that McEnroe, in the way he played tennis, controlled the game in the way a film director controls a film, or the way an actor commands the screen, or maybe both, or maybe neither. It is a film about time, which of course all films are about time, cinema is defined by its use of time, but so too, contends Faraut, does McEnroe control time in how he plays tennis.

It is in no way at all about the life and career of John McEnroe. It is about an idea, the idea that McEnroe, in the way he played tennis, controlled the game in the way a film director controls a film, or the way an actor commands the screen, or maybe both, or maybe neither. It is a film about time, which of course all films are about time, cinema is defined by its use of time, but so too, contends Faraut, does McEnroe control time in how he plays tennis.

A tennis racket handle hangs in mid-air before the torso of a man. A hand grips the racket. Feet step on white cut-outs of feet. Unlikely sound effects play for each action. What in the hell is going on?

So opens the movie, with footage of an instructional tennis film from the ‘50s. It is from the world of instructional sports films that Faraut springs. With access to untold feet of footage he came across the work Gil de Kermadec, who from the ‘60s to the ‘80s made instructional tennis films. His method was to film tennis players during matches, often using slow motion, in an effort to capture what no simulations could.

The manner in which tennis was shot for television was anathema to Kermadec. Only by shooting on 16mm film, and only shooting in the way he shot, could he begin to capure the kind of poetic physicality he sought.

In 1984, Kermadec focused on John McEnroe, then the number one ranked player in the world. He shot endless hours of McEnroe’s games on the clay courts of Roland Garros. It’s this footage that Faraut came across. In it he saw something that belied Godard’s quote. As Faraut puts it, “Because we are so conditioned by the video images of televised broadcasts, the cinematographic tecture of 16mm transports us quickly into the realm of fiction.”

Kermadec often films McEnroe in very tight shots. We can only see McEnroe, or at most McEnroe and most of his side of the court. We don’t see the other player. With this and nothing more we’re brought into a different kind of mental space. Shots like this pepper live broadcasts, but only for the seconds it takes one player to hit the ball. Then we’re back to the other player or the standard wide shot. Just staring at McEnroe, having no idea what the other player is doing, or even if the ball will be coming back to him, places McEnroe in the role of actor, of performance.

More performative still are McEnroe’s famous outburts at the chair umpires and line umpires, many of which Kermadec filmed. Faraut suggests that McEnroe used these outbursts to adjust the tempo of the game, to create pauses where there would otherwise be none. In one extended sequence, we see a call go against McEnroe. He argues and argues, seemingly to no purpose whatsoever. The call isn’t changed. At last he goes to serve again. And wins the point.

In one odd scene, over McEnroe’s outbursts we hear on the soundtrack Robert de Niro in Raging Bull asking Joe Pesci about possible indiscreet relations with his wife. Thus further tying tennis to the realm of film, of course. It’s a small, brief, but impressively out-there moment.

Later in the film, Faraut goes deeper into the psychology of McEnroe, at least as he interprets it, of how, so unlike other athletes, McEnroe, rather than fall apart when allowing his anger to burst out, uses this intensity of emotion, this feeling that everyone, not just his opponent, is against him, to raise his level of play. It’s a strategy, then. McEnroe himself claims that he practices how to use his outbursts to his advantage. Who knows if this is true.

Finally we reach the end of McEnroe’s ’84 season and arrive at the French Open against Ivan Lendl. Here Faraut lingers, letting us experience as much of the emotional intensity of an over four hour event as he can. If you don’t know how it ends, I won’t tell you.

It is immediately evident why Kermadec’s footage inspired Faraut to make this movie. It is striking and unique. It is cinematic in a way actual sporting events never are. He’s right about one thing: the footage brings tennis into a different realm.

As for the rest of the cinematic/philosophical musings of the movie, they are just that: musings, suggestive of much, proof of nothing. Given that so much of the movie is devoted to near close-ups of one man playing tennis, it is disarmingly hypnotic. To my eyes, it flew by. I was mesmerized.

And Faraut stumbles across the long-hidden secret that anyone even peripherally involved in tennis since the ’70s already knew: McEnroe threw tantrums on the court to boost his own game and throw off the rhythm of his opponents. He was an incredible player, but his emotional antics marred his exceptional skill.