Ah, fate! Inevitable, implacable, industrious, insidious, and many other words that begin with i, it comes for us when we least expect it, grabs us by the throat, and demands some goddamn answers, or else. Is fate even a thing? Is it but an idea? Is it death personified, coming for us all? We don’t know. For all we know, fate could be a frog in a stetson riding a badger. A deadly, killer frog. With laser eyes! For example.

Lucky for us, we have movies, and in the movies, inevitable doom comes often in a form easily recognized: a guy with a gun. Get in his way, you wind up dead. If he’s got you in his sights to begin with, forget about it. There’s no stopping him. You can’t reason with fate, though you’ll try. You’ll beg and plead, you’ll connive and plot, you might poke him in the eye and run, or get naked and sleep with him. It won’t help. He’s got one goal, and he will not be distracted from obtaining it.

Both movies in this week’s Mind Control Double Feature star fate itself. Mean, mysterious, bad-ass fate. It’s coming to get you. And it’s got a gun.

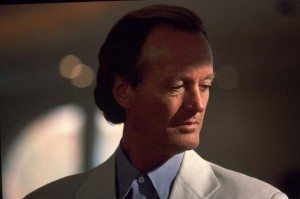

Point Blank (’67)

Lee Marvin wants his $93,000, and you’d better hand it over, now, or there’s going to be trouble.

Point Blank has achieved a kind of mythical status in the lore of movie nerds, though it didn’t make much of a splash when it originally opened. It’s a unique combination of surrealism, film noir, and ‘60s avant-garde filmmaking by director John Boorman, who’d only made one movie prior to it, and who went on to direct movies such as Hell In The Pacific, Deliverance, and Zardoz.

Lee Marvin met him and decided he was the one to direct Point Blank. There was a script, but Marvin tossed it. Instead, he and Boorman created something very different, and very strange.

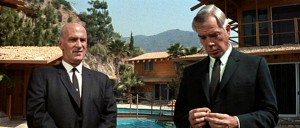

The plot is a simple noir kind of thing. It begins with a robbery in which Walker (Marvin) is double-crossed by his partner, Reese (John Vernon, who we like quite a bit here at Stand By For Mind Control, in his first film appearance), and left for dead. Walker, not dead (but see below), wants revenge, and wants his cut of the money, $93,000.

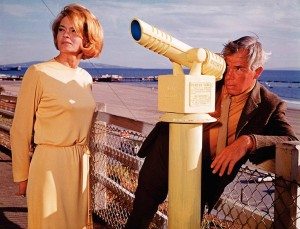

He’s pointed in the right direction by a shadowy character called Yost (Keenan Wynn), who may or may not turn out to be someone else by the end, and heads to Los Angeles to find and kill Reese. Along the way he meets up with Reese’s woman, Chris (Angie Dickenson), who’s Walker’s sister-in-law, and claims to hate Reese. She’ll do anything for Walker.

When Walker finally encounters Reese, he learns that Reese is part of a larger criminal conspiracy. He’s not the end-point of Walker’s mission after all. And so Walker heads up and up the food chain.

That’s it for the plot, which isn’t the important part. Point Blank is structured in a jagged fashion, with Walker’s memories intruding on the proceedings, with scenes played non-chronologically, with sounds and colors and cold, empty settings driving the movie forward. I’ve seen the movie numerous times over the years, yet it’s hard to remember precise scenes. It exists more as a series of impressions. The most memorable of these is Walker walking down a long, barren hallway in an airport, his shoes clicking on the tiles. This sound and image haunts the movie.

Unlike typical noir, Boorman doesn’t go in for dark and shadow. He shoots L.A. in blinding light. Different scenes are built up around single colors. Yet the locations all end up feeling kind of ethereally industrial. Parking lots, skyscrapers, airports. Everything is strangely empty and unreal. Walker himself is almost a part of the masonry. He’s essentially expressionless for the whole movie. He’s a force of nature. There’s no getting inside him. In one scene Angie Dickenson beats on him, just slaps him, hits him, pounds his chest for what must be a full minute. It’s hilarious. But Walker doesn’t flinch. She might as well be pounding on the walls. He’s going to get his money. That’s all. No one will stop him.

Boorman didn’t take as influences past film noirs or crime flicks. He was looking at Resnais, Leone, Antonioni, at European directors finding new, fractured ways to tell stories that didn’t focus on dialogue. The look of the film is a visual representation of the mind of Walker, in a very abstract way. We see what’s going on inside of him not through what he says or what he outwardly reveals, which is nothing; his interior is visualized as the exterior of the movie.

The finale takes place on Alcatraz (Point Blank was the first movie to shoot on the site of the recently closed prison island). Walker is finally offered his money. But will he take it? The end is not what you’d expect. Some have argued that the whole movie is but a dying vision of Walker’s, that he died in the opening robbery. Boorman has never stated whether he thinks this is true or not. The movie is left purposely open to interpretation. It’s up to the viewer what to make of Point Blank.

One huge fan is director Steven Soderbergh, who provides a commentary track on the Point Blank DVD. It was a big influence on him, perhaps nowhere more obviously than on his own man-seeks-revenge movie:

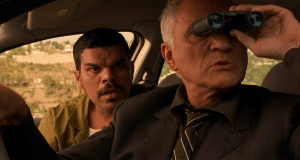

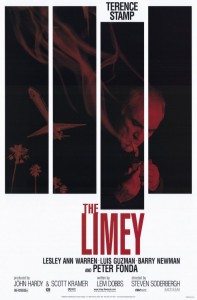

The Limey (’99)

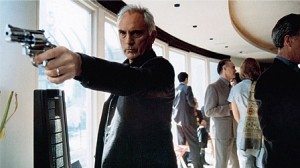

Terence Stamp wants to know how his daughter died, and you’d better tell him, now, or there’s going to be trouble.

Writer Lem Dobbs and director Soderbergh set out to make a movie in the vein of Point Blank and Get Carter with The Limey, both plotwise and stylistically. Soderbergh is an accomplished editor as well as a director, and has always been drawn to different ways of toying with time in film. Asked about his editing influences with regards The Limey, he says:

For this film especially, I’d say Petulia and Point Blank, but I love the early Alain Resnais films. Those had a huge impact on me when I saw them. Hiroshima, Mon Amour and Last Year At Marienbad are both still astonishing to me to this day. There are more ideas in the first 15 minutes of Hiroshima, Mon Amour than in the last ten movies you’ve seen. And he was, like, the first guy to do this stuff. You look at what he was doing and it’s just jaw-dropping. I haven’t done anything nearly that adventurous yet. But that’s what I had in mind when we were making [The Limey]. I kept saying, “Look, if we do this right, it’s Alain Resnais makes Get Carter.

Once again, we have a simple story of a man on a mission, in this case Wilson (Stamp), a British criminal just released from prison. He learns of his daughter’s death in a car accident, and doesn’t buy it. He flies to L.A. to find out what really happened. This leads him to his daughter’s older boyfriend, rich record producer Terry Valentine, who in an inspired bit of casting is played by Peter Fonda as a sort of sad, empty, burnt-out result of all that fun he had in the ‘60s. As you might expect, Wilson’s daughter didn’t die in a simple accident. And if you just watched Point Blank—which you did—you also might expect an unexpected ending.

That’s it for the plot summary. The beauty of The Limey lies in the telling. It jumps all over the place. Dialogue from one scene bleeds into other scenes, some that came before in time, some after. We cut again and again to Wilson sitting on the plane, and is he reflecting on what he’s done, or on what he’s yet to do? Events play out as they do in memory, without regard for chronology, and Wilson’s fantasies are indistinguishable from reality.

Soderbergh narrowed the focus of Dobbs’s story, pushing extraneous characters to the edges to leave Wilson and his daughter front and center. This didn’t please Dobbs, who felt Soderbergh screwed up his script. I’ve yet to listen to their joint commentary on the DVD, but word is that it’s a riot. It includes this bit from Dobbs:

People ask me, “Do you like this movie?” And as a disinterested, objective filmgoer who had nothing to do with it, I’d say it’s a good movie. I’d recommend it to my friends. But as a screenwriter, I think it’s crippled.

Though helpfully he also points out that Robert Towne thought Polanski ruined Chinatown, and writer Alain Robbe-Grillet thought Resnais ruined Last Year At Marienbad. Such is the fate of the screenwriter, to have some genius director go messing up your vision.

Credit goes to Dobbs for providing Soderbergh with a video copy of the ‘67 Ken Loach film Poor Cow, starring Terence Stamp, scenes from which are cut into The Limey to show Wilson as a youngster (Loach was happy to allow it). The trick works beautifully. The grainy quality of the black and white footage gives it an old newsreel vibe.

The Limey, in its use of Poor Cow and the casting of Fonda, creates a sense of picking up a story left over from the ‘60s, as if these two men, Wilson and Valentine, had been on hold for 30 years, and only now are allowed to play out the fate designed for them. It’s that reason too that makes it such a nice follow-up to Point Blank. The films feel a part of the same continuum in content, style, and history.

Now if you’ve been paying attention around here, you’ll recall that the Evil Genius included The Limey in his Soderbergh write-up from last year. That’s right: sometimes we write about movies twice. Why? Because we are all-powerful. So. Once you’ve watched these two, you’d better head over there and find out which other Soderbergh flicks you should enjoy next…