Who would you be if you could be someone else?

It’s one thing to wish you were someone in particular—Jack Nicholson, say; he seems to have had a pretty good time of it—but unless you’ve got a wizard or god almighty at hand, it’s not going to happen.

Merely wishing you were anyone but yourself, though, now that you might pull off. It’s going to be tricky. And even if you succeed, you fail, since whomever you end up being, once again you’re you. Will it be the same you? A different version of you? A you so new the old you will be remembered as a stranger?

Some people try on new identities like pants. Some are no one but themselves from the moment they’re born. Others morph slowly from one way of existing into another. Everyone dreams of escaping themselves at some point in life. Or at many points. Some people live their lives doing nothing but running.

In this week’s Mind Control Double Feature, Jack Nicholson’s going to take us on a little ride. He’s going to run so far from who he is he’s going to wind up not knowing who he was.

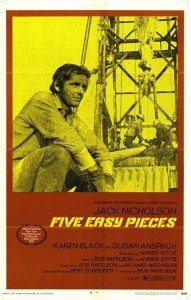

Five Easy Pieces (’70)

Jack Nicholson’s first real starring role made him famous. He made a splash the year before with his loopy supporting role in Easy Rider, but Five Easy Pieces is all Jack.

Jack Nicholson’s first real starring role made him famous. He made a splash the year before with his loopy supporting role in Easy Rider, but Five Easy Pieces is all Jack.

We meet Jack, as Bobby Dupea, working on a California oil rig. He and a buddy, Elton, hang out, go bowling, get drunk, pick up girls even though Elton’s married and Bobby has a girlfriend, a waitress named Rayette (Karen Black) who talks nonstop and drives Bobby nuts. But Bobby’s no prime catch himself. He’s moody and distant, like he’s treading water, waiting for something to happen.

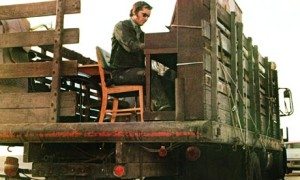

Then an odd scene comes along. Bobby and Elton are stuck in traffic on Highway 5. Bobby gets out of the car and jumps on the back of an overloaded pick-up truck on which he discovers a piano. He starts playing wildly. And well. Very well indeed.

Events take various turns, leading to the revelation that Bobby comes from a wealthy family of eccentric musicians. He was once a piano prodigy. It’s a life he ran away from. But when he learns that his father has had a stroke and is dying, he returns home to visit. “Five easy pieces” refers to the five classical pieces played during the course of the movie.

Five Easy Pieces epitomizes ‘70s filmmaking in its exploration of a rootless anti-hero, with no plot to get in the way. Bobby has no goal, no purpose, no sense of self. He doesn’t appear to know why he does what he does. He acts, is all. And nothing he does seems to satisfy him.

Writer/director Bob Rafelson, of Head fame (that’s the Monkees movie; Rafelson was also one of the creators of that band/TV show), made his best movie in Five Easy Pieces. It was the first movie made under BBS Productions, the short-lived but highly influential company at the heart of the “New Hollywood” era, which company would also produce The Last Picture Show, among others.

Five Easy Pieces was a hit. It made Nicholson a star. Strange to see what kind of movies used to be popular. Then again, this year’s Coen brothers movie, Inside Llewyn Davis, is remarkably similar in its plotless story of an anti-hero struggling either to create or escape his musical identity.

How does Bobby Duprea make out in Five Easy Pieces? I think it spoils nothing to say that he doesn’t stand still for long. He moves on to whatever comes next. What it is he doesn’t know. What it is he doesn’t care. As long as it’s something different.

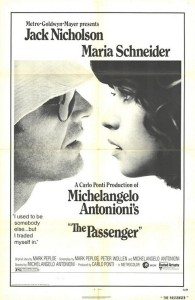

The Passenger (’75)

I like to think that when we meet David Locke (Nicholson), a journalist working in Africa, that he’s really Bobby Dupea with a new name and a new life. Try watching The Passenger with that in mind and let me know what happens.

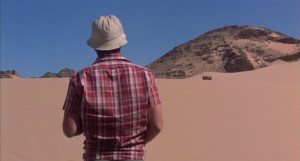

Locke is making a documentary. We meet him in the Sahara desert trying to meet up with rebels fighing in Chad. It doesn’t work out. Back at his hotel room, he finds that an Englishman he’d gotten to know, Robertson, is dead.

So Locke does what anyone would do. He takes all of Robertson’s belongings and tells the hotel manager that Locke died. His story works. To the manager, all white men look alike. Locke flies to Europe with Robertson’s appointment book and starts living the man’s life.

Turns out Robertson is an arms dealer, and soon Locke is, too. More or less.

Meanwhile, back in London, Locke’s wife learns that “Locke” died. One of Locke’s producers flies off in search of him.

And Locke gets deeper and deeper into this other man’s existence. Things become very confused indeed. The (next to) last shot is an incredible, seven minute single take, one that travels from a hotel room out to the desert beyond and back (and this before the invention of the Steadicam), and which brings the movie to a perfectly haunting finish.

The Passenger was directed by Italian Michelangelo Antonioni, the third of three English language movies he made for MGM. The first was the weird and elusive Blow-Up (a big hit) in ’66, then Zabriskie Point in ’70 (not at all a hit, generally loathed by critics at the time—but there’s naked hippies in it! And things blow up to the strains of Pink Floyd! So yeah, you might as well watch it), and finally The Passenger, which received much better reviews.

It holds up beautifully. Antonioni’s most famous Italian movies, L’Avventura, La notte, and Red Desert, are full of vast emptinesses and long takes. For Antonioni, the modern world is entirely alienating, and the spaces between people are infinite. The Passenger deals with similar ideas, but structurally it comes across as a more normal film. It has a clear story. It’s dramatic. It builds. And yet it too features long takes, vast spaces, and in the end leaves you wondering not only whether it’s possible to ever really know someone, but whether it’s possible to ever know yourself.

You will be a new person after watching these two movies. Who will you be?