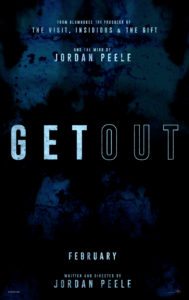

Get Out is that rare creature: A funny horror movie that’s both scary and funny. Not quite Evil Dead II funny and not quite An American Werewolf In London scary, but no matter. It works, from start to finish. It lives in the same world as Shaun of The Dead and Hot Fuzz, where genre elements are knowingly winked at while still being used in exactly the way a good genre movie uses them. Also like those beautiful Wright/Pegg flicks, Get Out’s writer/director Jordan Peele creates a real human being in his lead character, one whose past, when revealed, adds depth rather than boring you while waiting for the next joke and/or scare to wake you up.

Get Out is that rare creature: A funny horror movie that’s both scary and funny. Not quite Evil Dead II funny and not quite An American Werewolf In London scary, but no matter. It works, from start to finish. It lives in the same world as Shaun of The Dead and Hot Fuzz, where genre elements are knowingly winked at while still being used in exactly the way a good genre movie uses them. Also like those beautiful Wright/Pegg flicks, Get Out’s writer/director Jordan Peele creates a real human being in his lead character, one whose past, when revealed, adds depth rather than boring you while waiting for the next joke and/or scare to wake you up.

But what really sets Get Out apart from other horror comedies is its social commentary. It’s such a simple idea driving this movie, and no one’s done it before. A young white woman, Rose (Allison Williams), invites her black boyfriend, Chris (Daniel Kaluuya), home to meet her parents in their ritzy suburban home—and it’s played out as a horror movie akin to The Stepford Wives or Rosemary’s Baby or The Wicker Man.

Which is to say, it puts the viewer in the shoes of a black man in a white world more effectively than any movie I can think of. Being a pasty white man myself, I’ve never had to endure the kind of discomfort and persecution black Americans have to deal with their whole lives. I know it exists, but not what it feels like to live it. Yet by using The Stepford Wives template, Get Out puts you there instantly (well, “movie-there,” in any case).

Because in that type of horror movie, where an average somebody finds themself around a group of seemingly nice people—exceedingly nice, even—and begins to suspect something nefarious is up, we in the audience are right there with them. We suspect things even before they do. We’re primed to. It’s how these movies work. We hang on every word, every gesture of the “nice” people, waiting for them to sprout lizard wings or robot heads and go on a killing spree.

In Get Out, then, experiencing the white world with suspicion and dread is built into the genre. You’re there instantly, just like Chris. As a concept for a genre movie, it’s brilliant.

Chris is a low-key, forgiving kind of guy who doesn’t want to stress anyone out, doesn’t want to trouble anyone. It’s easy to see Peele in him (which I’m judging from the kind of vibe he has on Key & Peele). Whenever Chris brings up anything he feels is a little odd, a little off, even a little racist, and Allison’s reactions suggests she thinks he’s just seeing things, he backs off. “It’s okay,” he says, often, not wanting to start trouble.

Even the most innocent-seeming lines spoken by Allison or her parents, Missy and Dean (Catherine Keener and Bradley Whitford) are fraught with double-meanings. Which is to say, they’re not so innocent after all, not if you’re black, surrounded by white people, in a country whose founders enslaved your relatives.

I’m not about to reveal the nature of evil Chris encounters on his weekend in the suburbs, but it speaks to how white people historically and presently treat black people as less than human, as objects, as fine athletic or artistic specimens whose worth is both determined and limited by their DNA.

Dean is sure to tell Chris he’d have voted for Obama a third time, and waxes rhapsodic over Jesse Owens’s Olympic wins in Berlin, but no matter what he says, it’s dehumanizing and creepy. Chris rolls with it, though. At first. He’s used to it. He knows how to get along.

Only what about the black maid, the black gardener, and the absurdly dressed husband of that old white lady? What’s with their frozen grins and bizarre, robotic speech? It’s all a bit over the top, yet no matter how obviously messed up his situation is, Chris tries to be chill about it.

He talks to a friend back home, Rod Williams (Lil Rel Howery), proud employee of the TSA, who from the get go tells him it’s crazy to think he can make it in white suburbia unharmed. He’s the comic relief in what’s already a funny movie. He’s hilarious. I love his scene late in the movie going to the police—black like he is—with a story of what he thinks is happening to his missing friend. Their reaction is perfect. You think you know what the joke is, but Peele’s one step ahead of you. The joke is that the joke isn’t the joke.

Aside from Rod’s scenes, Get Out doesn’t play as a comedy. It’s a suspense/horror movie by design, but it feels designed from the perspective of a comedian. The horror tropes are all amped up in the same way a comedian would joke about them, only they’re still used for suspense and horror. So for example, Allison’s creepy racist brother, Jeremy (Caleb Landry Jones), late in the movie, at a terrifying moment, is revealed standing on the porch of his parents’ expensive house playing—no, not a banjo, this is a rich white hipster type—a ukelele.

Maybe, in terms of movie structure, Get Out has too much set-up and too fast a pay-off. It feels that way. I didn’t care, though. None of the set-up drags. It’s funny and weird and creepy and, in the hypnosis scene—Missy can cure anyone of smoking with hypnosis, don’t ya know—trippy. As for the pay-off, that’s where the horror comes in. It’s completely over the top. I didn’t care about that, either. Those white folks had it coming.

Oh good. I really want to see this one. I’m glad it is (based on your review) sounding better realized than Keanu.

Much, much better than Keanu. In terms of filmmaking and story-telling chops, it’s not on the level of Hot Fuzz, but it’s very smart, and just works.

I watched this again last night. I think it’s even better the second time through.

All of the Black actors are perfectly creepy playing Coagula-ted vessels, especially Lakeith Stanfeld. They way they talk and move and react is so icky-white, like Allison eating dry Fruit Loops individually while she listens to the Dirty Dancing soundtrack; impossibly, horrifically, white.

And the scene of her looking for her keys. That tension. So very right.

The scariest part is the very end, when he’s finally stopped choking Allison and then gets hit by the flashers on the cop car and you know there is absolutely no way he doesn’t get the chair for saving himself.