I watched Breathless (À bout de souffle) for the first time in a decade prior to checking out Linklater‘s newly released making-of-Breathless biopic, Nouvelle Vague, and, despite it long being hailed one of the masterpieces of cinema (most loudly, to be sure, in Cahiers du Cinéma, which publication, go figure, was a massive proponent of the French New Wave’s importance), despite its influence on the generation(s) of filmmakers to arise in its wake, despite it being, in places, perfectly entertaining and strange, I found it, overall, a bit too boring and pretentious.

Now, the first problem in finding anything about Breathless lacking is that one will be informed that this is certainly Godard’s entire point, that anything we think we like about movies is exactly what’s lousy about them. Story? Characters? Hollywood crutches. And yet. One does yearn, watching Breathless, for something like a story to follow or characters with traits beyond their cool vibes to engage with. Though it’s more compelling than anything else he would ever make, it still suffers from what all of Godard’s movies suffer from: The sense that one isn’t watching a movie at all, but rather some kind of vague philosophical attack on them, made by a man with vanishingly little to say. But, of course, saying it in the form of a movie. Because long live the revolution and so on. He was most fond of making the point that, when you’re watching a movie, specifically one of his, you’re watching a movie. Whoa, man. Pass the bong.

Don’t take my word for it. Here’s what Ingmar Bergman had to say about Godard:

“I’ve never gotten anything out of his movies. They have felt constructed, faux intellectual and completely dead. Cinematographically uninteresting and infinitely boring. Godard is a fucking bore. He’s made his films for the critics.”

And Werner Herzog:

“Someone like Jean-Luc Godard is for me intellectual counterfeit money when compared to a good kung fu film, a Fred Astaire picture, or a porno.”

Still and all, one can’t–and shouldn’t–get past the fact of Godard’s influence on other young filmmakers of his era, and of many eras to come. The jagged jump cuts of the film, very unusual at the time, have since become the norm. For Godard this came in part from his philosophy that all of the boring bits of every scene should be chopped out, and part from that fact that he purposefully shot it without any concern for continuity or for how scenes would cut together. Which maybe that’s the same thing. He went at the making of the film with the attitude that all such rules be discarded. Did he know how he’d edit the film prior to the editing stage? Recollections of those involved say no; he discovered the need for the cutting style in the editing room. Thus his philosophy, insofar as editing goes, was born of necessity: his film was too long.

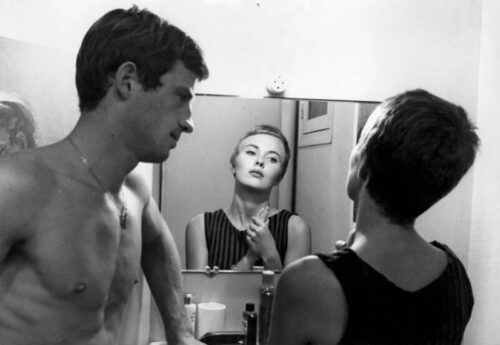

Almost one third of Breathless‘s 90 minutes is spent on one scene in a tiny apartment, with Michel (Jean-Paul Belmondo) and Patricia (Jean Seberg) talking and flirting as they slowly get around to sleeping with one another (skipped over in another abrupt cut). For many future filmmakers, this alone was seen as a kind of revolution. To think, one could just have people in a room, talking about nothing, for 25 minutes. Tarantino wouldn’t have a career without this scene. Neither, one supposes, would Linklater.

I remembered the movie being somehow more about nihilism than it is. It’s not about anything. Which is almost the same thing, but not quite. The movie has no thoughts on nihilism. It has no thoughts. Which this is what’s seen as its depth, the balls it has to not have anything at all on its mind (a convenient emptiness left for critics to fill, and fill it they do, to this day). Who would dare do such a thing? For other filmmakers, this was freeing. For an audience today (well, for me, anyway), it results in a film that has no idea what it is or what it wants to be, while yet communicating clearly that this very fact is the one it’s most proud of. Put that way, it sounds kinda punk. Which is perhaps why it made such a splash.

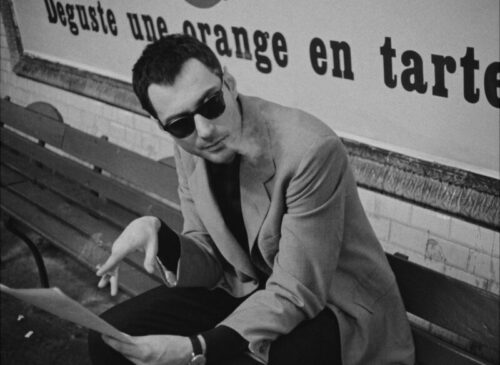

Richard Linklater’s Nouvelle Vague is not punk. It is a fawning love letter to an era, to Godard, and to Breathless. Visually, it’s quite lovely. Shot with old lenses, on I don’t know what kind of black and white film stock, it does what many movies that set out to replicate the look of old films fail to do: it looks like a film from the era. That is, purely in the sense of its visuals. The movie itself will not be mistaken for one made in ’60. I caught it on 35mm, and if you’re going to see it, it’s worth seeking out a print of it before it heads to Netflix in, I presume, the next five minutes (good luck!). The cast is solid, and it’s a mostly entertaining softball of a biopic.

Which feels wrong. Linklater has said he wanted to capture the innovative, daring feel of Breathless. Maybe, in the making of it, he managed that, for himself. But in its presentation, there is, again, nothing punk about this movie. It’s as safe as safe can be, from beginning to end. After a fair amount of Godard putting his pieces in place, the movie settles down into ‘the making of Breathless.’ Shot in 20 days, Linklater plays out at least one scene for every day of shooting. It’s all perfectly lightly amusing, but lacking, as it does, any drama or stakes whatsoever, it winds up dragging toward the end. One reads the numbers on screen–of each shooting day–willing them to go by faster. Only then once they’ve hit 20, all we get are one scene of an angry producer insisting on a 90 minute movie, one scene of Godard with his editors expounding on his new theory of editing, and one scene with Godard and friends in a screening room watching the finished film in stunned awe at his genius. The end.

Something feels missing here. There’s no dramatization of the film’s reception. There’s no dramatizing anyone’s reaction to what Godard did. The film assumes that we’ve seen Breathless, and that we find it a masterpiece. Full stop. A big part of the enjoyment of this kind of story is putting yourself in this place and time and seeing the reactions of the people who were there through their eyes. But we get none of this. It’s simply assumed that everyone involved, despite their doubts as to Godard’s mad process, is thrilled with the outcome. Which why not, I guess. It was a huge hit.

Godard shot Breathless without synced sound, meaning no dialogue recording while filming; no sounds of any kind at all. Wouldn’t it have been interesting to see, for example, Jean Seberg’s (Zoey Deutch) reaction to the movie once it was cut together, while recording her dialogue? Seberg gets the short end of the stick in this movie, played as a scold throughout, who never gets what’s going on, and wants nothing to do with it, who’s just glad to get away from Godard when it’s over. It’s a shame we don’t get to see her reaction to the finished film. Or anyone’s.

What Nouvelle Vague lacks it lacks, perhaps, on purpose: It has nothing to say about its subjects. Same as Breathless itself. Yet in Breathless this was what felt new and daring. It feels neither new nor daring in Nouvelle Vague. The point of the movie seems to be nothing more than to spend two hours with a genius while he makes his genius movie. There is nothing critical of Godard. There isn’t anything at all about him. He just is. His every line is played as a pithily wise bit of philosophizing. But is it wise? I refer you to Bergman and Herzog above. One supposes that, if the presumption going in is that Godard is a genius, which appears to be Linklater’s belief, then all of Godard’s pronouncements are to be read at face value: A genius bold enough to go against what everybody says about filmmaking, and to make a film his way. Which, sure, he did make it his way, and Breathless became the film that it became, so I guess all his obnoxious philosophizing was right? Only what if Breathless doesn’t play as a work of mad genius? But as an oddball, thrown together experiment more impressed with itself than anyone watching it could ever be?

In that case, one would wish for a more insightful purpose driving Nouvelle Vague. One might even have cause to recall Tim Burton’s masterpiece, Ed Wood, another film about the making of a film by a daring iconoclast certain of his own genius, yet one bristling with the emotion, insight, and drama not found in Nouvelle Vague.

But okay, even if we (we who don’t love Breathless) concede that in the larger scheme, Breathless is a “great film,” we might still wish Linklater had come up with a more radical presentation of its making, one that captured in whatever way original to Linklater a sense of daring and boundary pushing (maybe shooting it in French satisfied Linklater’s desire to push boundaries?). The film’s safeness feels like its biggest weakness. It’s a film meant to do nothing but allow us to moonily sigh and say, “Gee whiz, that sure musta been grand back then.” Which is to say, Nouvelle Vague is a movie made for a very specific audience: The one that knows and loves Breathless, and is happy just to bask in its reflected glory. This is all well and good, I suppose. Unless, like me, that isn’t you. In which case it’s a mildly diverting curio leaving one very much wanting.

Which is also my review of Breathless. It’s blasphemous to say so, but the truth is, I like the American remake better.

I never got Breathless (or saw the remake). It’s… unmemorable. And I don’t remember pretty much anything about it but a lot of cigarettes.

And Nouvelle Vague sounds strange, because Linklater HAS made genuinely genius films, in iconoclastic ways, that do have meaning beyond style. Boyhood, of course. And I love A Scanner Darkly for how it makes the source material visual in a way that’s right. So it’s a love letter, I guess, to material I don’t love.

I don’t think I’ll watch it, or Breathless.

I don’t know where you got that Linklater or the film supposes that Godard is a genius or lets him off the hook. I think it skewered him pretty well. He’s very much the pretentious blowhard I imagine him to be. Doesn’t the fact that the film doesn’t portray Breathless’s reception leave it up to us to decide what we think of film and its success, and of Godard? Linklater’s movie is very enjoyable, and I’m glad I saw it in a theater. It’s a much more fun watch than Linklater’s other one that’s out, Blue Moon, which is good but very squirmy. Go see it, Evil Genius!

I got that idea because the film is made based on Linklater’s love of the movie and the era. That seems beyond self evident. It’s literally why it exists. YOU think it skewered Godard? Okay. Probably because you don’t think Godard is some kind of cinematic genius (a wise thing to think, I think). But many, many, MANY people do. To the point that it’s simply an assumed state of affairs, in the world of the cinema literate. Bergman and Herzog are outliers. Godard is revered as a holy saint of filmdom by most.

I see what you mean in a general sense, that the movie just shows us Godard, so hey, we’re left to decide for ourselves who he is and how good Breathless is. Yet the entire tone of the film belies this idea. It’s a love letter, from start to finish, and not subtly. I have a hard time seeing how you could see otherwise. Linklater is up to nothing subtle here. He wanted to make a fun film celebrating a beloved movie and the young director who flew in the face of convention to make it. And that’s just what it is. Which is probably fine, if one loves Breathless. I happen not to, so it all felt a little tiresome by the end.

Doubt I’ll see Blue Moon in a theater. Or, possibly, anywhere else. But perhaps, sooner or later.