Let us begin by recalling this immortal exchance in Barton Fink between Barton and his agent, dining in the studio commissary:

Geisler: You need guidance? Talk to another writer.

Barton: Who?

Geisler: Jesus, throw a rock in here, you’ll hit one. And do me a favor, Fink. Throw it hard.

The life of the writer is one spent dodging rocks. Look at us here at Mind Control, slaving away, night and day, and for what? For money? Ha! There’s no money on the internet. For joy? In writing? Don’t be daft. Writing is nothing but an endless, miserable search for a truth that doesn’t exist. For adulation? We should be so lucky. We write because not to write would be worse. That’s how bad it is.

Writers are dangerous. They put ideas into people’s heads. Worst of all, they put ideas into their own heads. They’re clever that way. They’re very convincing. They have to be if they want to write. They can make themselves believe anything, and what better to believe than the craziest loopidy-do fantasies they can come up with?

For this week’s Mind Control double feature, we explore the minds of two writers, one real, one fictional, who, using their formidable literary powers, write themselves into early graves.

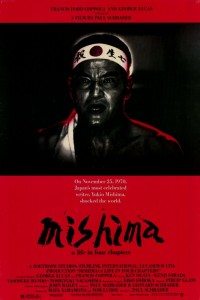

Mishima: A Life In Four Chapters (1985)

Yukio Mishima was the most famous writer in modern Japanese history. Yes, even more so than Haruki Murakami, you literary hipsters, you. First published in 1946, he went on to write 34 movels, 50 plays, short stories, and essays, before his death in 1970 at the age of 45.

Yukio Mishima was the most famous writer in modern Japanese history. Yes, even more so than Haruki Murakami, you literary hipsters, you. First published in 1946, he went on to write 34 movels, 50 plays, short stories, and essays, before his death in 1970 at the age of 45.

His last four books comprise a tetralogy called The Sea of Fertility (read them; they are amazing). He finished the last book just before he died.

This was no accident. His death was a meticulously planned, ritualistic suicide, staged at an army camp, that began with something like an attempted coup. Those four books he wrote leading up to this act in many ways foreshadow it. Mishima was a writer who joined his writing with his life in the most extreme way possible.

Paul Schrader’s film of his life plays out partly in the present of ‘70, the day of the suicide, partly in flashback, and partly as recreations of three of Mishima’s books. Here’s Schrader on the books he chose:

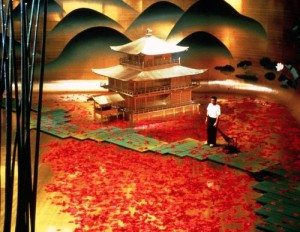

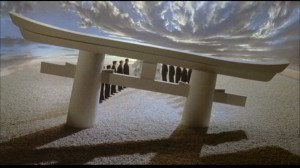

You wanted one that represented aestheticism, you wanted one that represented sexual decadence, and a third that represented a kind of military action. Runaway Horses and The Temple of The Golden Pavilion were obvious choices [military action and aestheticism, respectively] and the obvious choice for the sexual decadence would have been Forbidden Colors, his only overtly homosexual novel. The widow, who was kind of a professional widow and did not want the homosexual element to be dealt with, said that was the one novel that I could not have. There was a novel called Kyoko’s House, which had never been translated into English and had a character who was an actor whose drama had some of the same policies as Forbidden Colors. I had Kyoko’s House translated and I was able to get what I was looking for in Forbidden Colors through that story.

Each of the fictions are shot with abstract stylization and unique color palettes, while the flashbacks of Mishima’s youth are presented in black and white. Taken together, the different elements create an impressionistic vision of Mishima’s life and beliefs, one much more affecting than you’d get from a straight biopic.

Adding to the dreaminess is Philip Glass’s score, among his best, which includes instruments unusual in Glass’s repertoire, such as ‘50s era electric guitar.

Since his huge success writing Taxi Driver (’76), Schrader has had a career with many ups and downs. He’s written quite a few excellent scripts—Raging Bull and The Mosquito Coast come to mind—but his directorial output has been considerably spottier. Mishima is his best movie as a director, full of passion and creativity. Considering the four movies mentioned in this paragraph, we can say this much: Schrader is fascinated by men consumed and destroyed by their obsessions.

As implied above, Mishima is more or less assumed to be homosexual, though on the other hand, his widow and children have worked hard to claim otherwise. He was a man driven by passions. He became obsessed with weight training and kendo. He felt that valuing the mind over the body was a grave mistake. He became a nationalist towards the end of his life, adhered to the code of the samurai, and thought it a terrible mistake for the Emperor to have renounced his claim to divinity after World War II.

It’s fair to say that the Japanese have a complex, tortured relationship with Mishima. Schrader’s film has yet to be shown in Japan.

Oh, the trouble a writer can cause. But it gets worse:

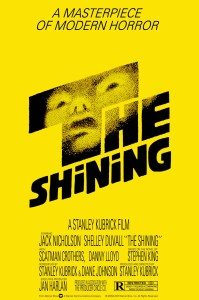

The Shining (1980)

The only thing worse than a genius writer fusing his work with his increasingly insane life is a failed one whose writer’s block drives him into violent madness.

The only thing worse than a genius writer fusing his work with his increasingly insane life is a failed one whose writer’s block drives him into violent madness.

Perhaps you’ve heard of The Shining? Litte movie, came out a few years back, directed by Stanley Kubrick, who with co-writer Diane Johnson adapted it from Stephen King’s novel in a manner King never cared for.

It met a mixed reaction when it came out, but has since grown into a massive cultural juggernaut. People who love horror movies love it. People who hate horror movies love it. People who love axe murderers love it. Even people who hate Shelley Duvall love it. The only people who don’t love The Shining are people who hate having the shit scared out them.

It’s especially loved by conspiracy theorists, who see in Kubrick’s meticulous artistry evidence of whatever they want to see, be it a faked moon landing, the murder of Native Americans, or whatever else they rant and rave about in a documentary made about the phenomenon, Room 237, named after the room Danny-boy is advised to keep out of. In the book it was room 213, but the folks at the Timberline Lodge, used for exterior shots of the Overlook Hotel, asked Kubrick to change the number to one not in use by the lodge, for fear of scaring off customers. Bad call. Imagine the waiting list to stay in room 213 of the Timberline Lodge if he’d kept it.

It opens with one of the creepiest, and simplest, credits sequences of all time, following the car of one Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson), writer and ex-alcoholic, soon to hire on as the winter caretaker of the Overlook Hotel in Colorado. He’s to live there with his wife and son and work on his new novel in the peace and quiet of the vacant hotel.

Unfortunately, either he goes nuts or the hotel is cursed by evil demon spirits, depending on how you interpret these things, and trouble ensues.

His son Danny has visions of blood and death and rides around the hotel on his Big Wheel, in long, eerie Steadicam sequences, one of the first movies to use this new invention after its introduction in Bound For Glory in ’76. As ever, Kubrick figured out what do to with it more effectively than anyone before him.

The Shining is a weird movie that grows weirder the more you watch it. It’s slow and hypnotic. None of what happens may actually be happening. What’s real and what’s imagined is iffy from the start, and as for what’s imagined you also begin to wonder who’s doing the imagining. One of the characters? All of them? You?

The hotel feels like it goes on forever, inducing a feeling of vertigo, yet at the same time it feels constricting and oppressive, snowbound, like you can’t breath and you’ll never find your way out.

When first released, it included a final scene of Danny and Wendy recovering in a hospital, with hotel manager Ullman there telling them that Jack’s body was never found. Kubrick decided almost immediately that the scene didn’t work and instructed all theaters to cut it out of their prints and send the piece of film back to Warner Bros.

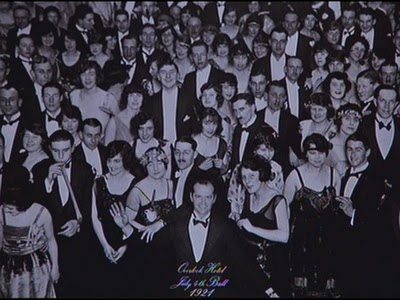

This was a wise decision. The movie needs no closure, no explanations, no added mysteries. The photo is enough. What’s Jack doing in it? How did he get there? What the hell just happened? Simple. Jack is a writer. That’s his problem. He falls too deep inside his own creative mind and never escapes.

It’s a tough life being a writer, and as Jack Torrance and Yukio Mishima show us, it’s a tough death too. Throw a rock if you must, but do me a favor—throw it soft.

Mishima is brilliant. Not so easy to be part of, but oh-so worth it. A curious double bill; perhaps I shall have to give it a spin. Been ages since I’ve had the Shining on.

It is kind of curious, this double bill, but something about it makes sense. I think.