In ’61 and ’62, social psychologist Stanley Milgram devised and ran one of the most famous experiments in the social sciences, wherein subjects were asked to give increasingly large electric shocks to other subjects based on answers to a memory test. They were told it was an experiment on the effects of negative reinforcement on memory. In fact the only subjects were the ones giving the shocks. The other “subject” was a compatriot of Milgram’s who played a recording of himself groaning in pain and begging for the experiment to stop as the voltage was increased. About 65% of participants gave the maximum shock possible, 450 volts, despite evident discomfort in doing so. Why? Because an authority figure, a scientist, told them they had to continue. What this implies about human nature has been depressing and upsetting people ever since.

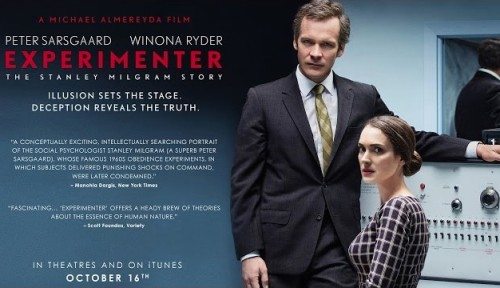

Filmmaker Michael Almereyda tells the story of Milgram’s obedience experiments and their fallout in Experimenter, an unusual and intriguing movie in which the typical crutches of bio-pics are nowhere to be found.

Peter Sarsgaard plays Milgram, a Jewish scientist intrigued by Nazi Adolf Eichmann’s defense when caught and put on trial: he never did anything without being expressly ordered to by his superiors. Why, wonders Milgram? Or more exactly, how? How is it possible to make a person do something they know is wrong?

Experimenter opens mid-obedience experiment, with Milgram watching his subject squirm, yet continue to increase the voltage of shocks. At a certain point, Milgram breaks the fourth wall and narrates his own story. This continues throughout the movie, and seems to fit the character of Milgram perfectly, this very low-key, scientific fellow, as he describes in dispassionate detail the events of his life. Other tricks are used to increase the feeling of theatricality, such as Milgram and his wife, Sasha (Winona Ryder), having dinner at another couple’s house, the interior of which is just a screen backdrop with four chairs set in front of it.

The story follows Milgram chronologically from the obedience experiments to his death at age 51, but spends unusually little time on his personal life. He marries, has kids, exhibits a bit of emotion over personal problems now and again, but most of the movie is focused on his experiments. Rarely has a bio-pic about a scientist been so interested in the science. Experimenter is about as far from (for example) The Imitation Game as possible (and will no doubt be far less popular because of it, alas).

The obedience experiments are not warmly received. Questions arise over Milgram’s morals in lying to subjects and causing them mental anguish. The American Psychological Association holds up his application for membership and Harvard denies him tenure, despite, as he points out, 85% of his subjects saying they were glad to have participated.

What becomes clear is that Milgram’s findings are so upsetting that the focus must be thrown elsewhere. His morals, his methods, his findings, his conclusions. Everything is questioned so as to avoid the real question: Why will people cause harm to others when told to do so by an authority figure?

Milgram devises other intriguing social experiments detailed in the film, but none would bring him the kind of fame and renown as his obedience experiments, variations of which he continued to do for many years. With the eventual publication in ’74 of his book, Obedience To Authority, Milgram gains a wider acceptance (and ten years later, in 1984, owing to the renewed interest in George Orwell’s book about totalitarian oppression, Milgram has his biggest year ever in terms of speaking engagements and publicity).

Milgram becomes so widely known in the ‘70s that a CBS movie-of-the-week is made, dramatizing the experiments in absurd and, to Milgram, aggravating fashion. It’s called The Tenth Level and stars William Shatner as Milgram and Ossie Davis as his black friend (this is the ‘70s, remember). It’s not available on DVD or VHS, but you’re damn right it’s on youtube. I just watched a bit. It’s pure Shatner. Check it out. Sad to say, the guy playing Shatner in Experimenter, Kellan Lutz, has the least Shatnerian affect I’ve ever seen. The guy’s not even trying! But Dennis Haysbert as Ossie Davis is perfect. He’s almost a dead a ringer.

Sarsgaard is excellent as Milgram, playing him as understated and intellectual and just slightly odd, though in the second half of the movie his beard has a tendency to upstage him. Winona Ryder, not often seen on screen these days, looks like a spindly, wintry bird you might find one snowy January morning perched inquisitively on a distant fence beyond the barn. Or so I imagined. She’s good.

Jim Gaffigan, Anthony Edwards, Lori Singer, and John Leguizamo show up here and there too, giving this small movie a sense of being filled with recognizeable faces.

Experimenter isn’t thrilling or tear-jerking. It’s as low-key as its narrator and subject, and it’s wall-to-wall science (well, if you want to call “social science” science, it is, you prickly physicists, you). As Milgram narrates, his work would come to be standard material for students. His experiments on obedience have been replicated the world over. Across time and cultures, the results are essentially the same. The fact is, in the face of authority figures, no matter who they are, people will do as they’re told more often than not. Not a comforting truth, is it? If you want to see this kind of thing played out in the most uncomfortable manner possible, check out the little seen Compliance (’12), a true story you won’t believe is true. Milgram? He wouldn’t be surprised in the least.