Lately making the rounds is a video by something called RocketJump Film School titled “Why CG Sucks (Except It Doesn’t),” which if you haven’t seen, here it is:

TL;DW? To sum up: With snarky, smug voice-over, we’re told that to dislike computer effects in movies is to be some kind of knuckle-dragging troglodyte unaware that much of what we see in big movies is faked by computers—in ways we don’t see at all! You know, like crowds in crowd scenes, explosions, vehicles, buildings, clouds, etc.

It goes on to argue that even beyond background objects, the only foreground monsters and superheroes and whatnot we dislike are the bad ones found in bad movies. In good movies, apparently, nobody minds CGI, so to complain about it generally is to be, according to this video, a dumbass.

Problem is, this argument avoids the actual issue. Anyone with even a passing interest in special effects understands the many subtle uses of CGI, and are perfectly happy having this almost magically powerful tool in the filmmaker’s toolbox. We might wish it were used a tad less frequently, we might wish it weren’t so easy for lazy filmmakers to replace squibs with fake CGI blood and explosions with fake CGI fire, but this sort of thing doesn’t ruin movies, it’s just laziness, which humankind will not be ridding itself of anytime soon. To do so would take far too much effort.

No, the problems with CGI lie elsewhere.

Let’s begin with the issue of realism vs. fakeness. Makers of effects have always yearned for realism. From A Trip To The Moon to King Kong to Forbidden Planet to 2001 to The Thing to Keanu Reeves to Jurassic World, making the fake look real is the name of the game. But prior to CGI, “realism,” or what passes for it, came in many different guises. What we had was stylized realism, a kind of realism that even when it was the best money could buy and the best artists could design didn’t actually look real. Does the alien in Alien look real? Not at all. It’s a guy in a wild alien suit. We know it is, but it’s such a great suit, and it’s shot so well, we accept it. It’s stylized realism, and it looks fantastic.

Does the alien in Alien look anything like the alien in The Thing? Not in the least. Does the thing look real? It does not. It looks “real.” It’s stylized gory weirdness. It’s obviously fake but so well-made and so imaginative our brains are happy to accept it. Does the exploding head in Scanners look like a real exploding head? Beats me. I’ve never seen a head explode. I’ve seen one explode in Dawn of The Dead, but that one looked way different. And just as “real.” To this day both of those scenes are seriously disturbing.

How about the spaceships in The Empire Strikes Back? And the AT-ATs? Our brains are more than happy to accept those stop-motion models for the real thing, even though not for a minute do we doubt that they’re models. For an even more extreme example, take a look at Yoda. Being a Muppet, he’s about as far from real as you can get. But has anyone, ever, watched Empire and said, “I liked that movie except for Yoda. He was so fake looking.” No. They have not.

What about the fully CGI Yoda of the prequels? He still doesn’t look real. But here’s the thing: every effort has gone into making him appear so. And in failing to achieve total reality, he is a failed effect. This is CGI’s major issue: it has one goal, to literally mimic reality. In failing to do so, our brains register its inherent fakeness.

What practical effects create is an artistic slant on reality, and it’s this kind of fakery our brains like. We know what we’re seeing is a model or a puppet or a rubber suit, but given weight by good writing/directing/acting, our brains are happy to fill in the gaps.

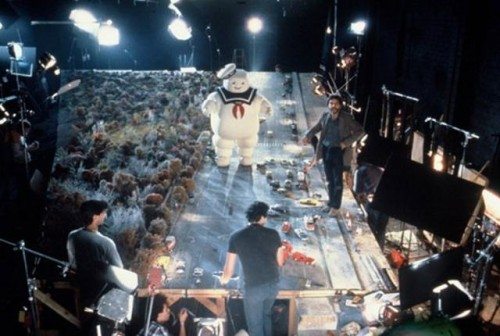

What’s more effective, the Stay Puft marshmallow man marching through New York or the most recent Godzilla stomping through San Francisco? Which is more compelling? Godzilla looks more “real,” but the Stay Puft marshmallow man is art. Or take Iron Man and the Hulk beating the hell out of each other in The Avengers sequel. Nothing about the scene is in any way engaging. It’s two CGI blobs smashing up a wholly CGI landscape. Watching it one feels removed from the action, pushed out instead of invited in.

We might then ask, if that’s the case, why do fully animated movies work? They work because they’re consciously stylized. Nobody in Spirited Away or Inside Out or Fantasia looks anything like an actual human being. Their goal isn’t to mimic reality, it’s to stylize reality in order to best bring out the emotion and drama of the characters and story. In this way, animated movies have more in common with practical special effects than with CGI-laden movies.

No offense to the artists working so hard to make giant lizards and robots, but once we get past any unique design choices, what they’re aiming to achieve is a generic, interchangeable realism. In Ghostbusters, they were trying to achieve a cool effect. In a sense, they both succeed, but in the former case, to put it bluntly, who gives a shit?

The video above says we only notice bad CGI, that the bad is all we’re complaining about, and this is absurd. Does nobody notice the CGI in Marvel movies? Noticing effects isn’t the problem. The problem is how those effects affect us.

I’m far from the first to point out that one reason our brains like practical effects so much more than CGI is that however fake they may look, practical effects are actually present. Models are real objects. Yoda is a real puppet. Exploding heads are real rubber and goop. It’s easy to forgive fakery when it’s physically present. I can’t say, biologically, why our brains function thus, but they do. CGI placed in real environments, or even in fully CGI environments, register as unreal. A serious problem when the only goal of the effect is to mimic reality.

People complain of too much CGI not because they see too much bad CGI, but because they see too much CGI. It creates a feeling of disconnection from actual objects and people. We’re always going to be more freaked out by a guy in a Godzilla suit than a CGI lizard. We’ll concede the CGI lizard looks way more real, and yet…the way more real lizard isn’t affecting us the same way as the man stomping on models.

So maybe what I’m getting at is the emotional versus the logical. Our brains may logically concede that the best modern effects far outshine past attempts in their mimicry of reality, yet we continue to respond emotionally to actual objects, whether or not we see through the trickery. Yoda is a perfect example. In Empire, he’s the most affecting character. In the prequels, he’s a CGI blob bouncing up and down. Ask yourself this: if you’re going to see some trashy movie with cheap special effects, would you rather they were cheap CGI effects or cheap practical effects? There is only one answer. We know what cheap CGI effects looks like. They’re exactly the same no matter the movie. They’re not funny. They’re not suprising. They’re just, simply, bad. But cheapo practical effects? They will be unique to whatever movie they’re in, and they will be delightfully hilarious.

CGI is being used for the wrong reasons. It’s not merely that it’s being used too much—which it is—or being used badly—which it also often is—it goes beyond that. CGI is used to trick us into accepting the fake for the real when that’s the very thing it’s worst at. The video makes this point, then fails to understand the point it’s made, that CGI is indeed at its best when we don’t notice it, but the only time we don’t notice it is when it’s not the focus of what we’re watching. When the focus is superheroes and monsters and space battles, the places CGI is most evidently on display, it’s at its worst, no matter how cutting edge it is.

It’s true many effects look better now than in the past, and, personally, being a grumpy old man, it’s easy for me to shine a fond light of nostalgia on the movies of old, but this doesn’t excuse CGI from so often being boring. That’s it’s greatest sin. Forget about sucking. It’s boring to watch the same giant lizards stomp their way through every movie. If filmmakers want to use this tool to its fullest, they need to recognize it as another form of animation and use it as such—imaginatively, uniquely, weirdly.